You can think of the zoos inaction in either of two ways: (1) this seemingly impressive group of American conservationists is just too amorphous and internally divisive to reach consensus on anything; or (2) like so much of America right now, doing nothing is the greatest achievement possible.

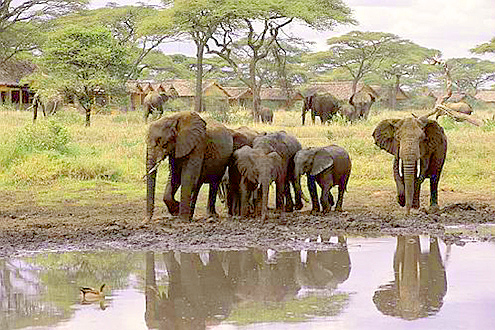

This is particularly true in light of the recent Nature article in which virtually every important researcher in the Serengeti signed on. This included the Americans George Schaller of the Bronx Zoo, Anna and father Richard Estes, Andrew Dobson of Princeton and the adopted American, Charles Folley. They were among 27 prestigious scientists who contributed to an article entitled, “Road will ruin Serengeti.”

And there’s more at home:

Tanzanian media, which while not government controlled is certainly government suppressed, has been growing increasingly bold in opposing the proposed construction.

Dar-es-Salaam’s largest newspaper, The Citizen, today reposted an old story about UNESCO considering withdrawing the Serengeti’s World Heritage status if the road is laid. What’s so interesting about this is that the paper got the permanent secretary, the career civil servant who heads Tanzania’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism, to lie … sort of.

While it takes reading between the lines, I’m absolutely certain this is what the article intended. Dr Ladislaus Komba told The Citizen that UNESCO had “suspended its warning” after being assured that new environmental studies would first be conducted.

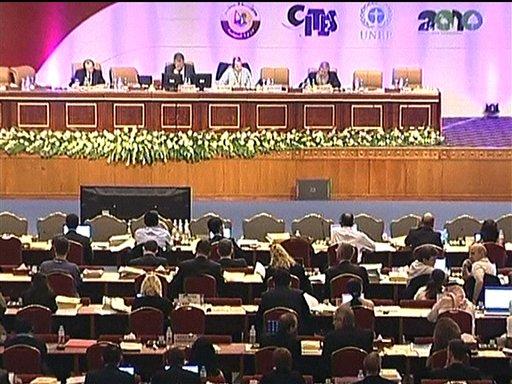

That’s probably not true. At least UNESCO will not confirm its true. The last policy report focusing on the Serengeti issued by WHC can be read by clicking here and that was in 2003. At the recent meeting in Brasilia, there was resolution statement that is, indeed, a warning that policy could change if the road is built.

But The Citizen has unmasked Komba for inverting events. The Tanzanian government offer to make new environmental studies came well before the WHC conference in Brasilia last month, where all the news and hearsay, and “warning” was reported.

But The Citizen has unmasked Komba for inverting events. The Tanzanian government offer to make new environmental studies came well before the WHC conference in Brasilia last month, where all the news and hearsay, and “warning” was reported.

There has been no official suspension by WHC of that warning. In fact the warning warns they better make good on past promises, which include a better environmental study than currently on the table. So no official suspension of anything, therefore. And page one news in Tanzania, now.

There’s been a lot of dosie-dose going around the ridiculous presumption that forceful opposition will make the Tanzanian leadership close ranks on this issue. First of all, that just isn’t true. There has been much forceful opposition (double-down on that Nature article) from the getgo. And now the Kenyan Government itself has become involved.

The wimps have claimed the Kenyans have been silent, because they too didn’t want to upset the Tanzanians any further. Balderdash. The Kenyans have had other things filling their agenda… like a new constitutional referendum, a World Court investigation of their politicians and war on the border with Somalia.

So I have to admit I was pleasantly surprised when Komba’s counterpart in Kenya, Mohammed Wa-Mwachai, issued a statement last week that said in part, “We have instructed our Tanzanian High Commission to set the stage for negotiations [about the Serengeti highway] and we hope to come up with an amicable solution.”

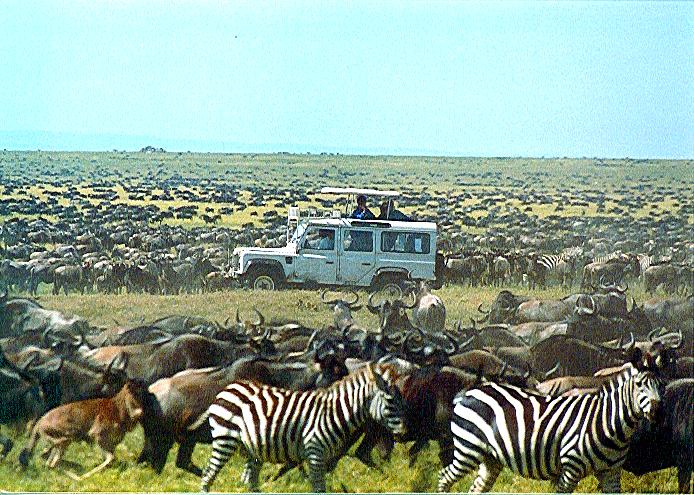

The Kenyans, actually, have the most to lose. Their one great remaining game park with large herbivore herds roaming the plains is the Maasai Mara, the top of the Serengeti ecosystem. The reduction of the current 1+ million wildebeest to less than 300,000 as estimated by the Nature article would cripple Kenyan safari tourism.

So we’re sorry that the American zoos were composed mostly of invertebrates, but keep the pressure up. In sum, the news has been good!