Quick! Hide! The toad’s approaching!

Quick! Hide! The toad’s approaching!

Like kudzu, loose strife, wolves and coyotes, garlic mustard, Asian beatles and now even Asian carp, this week poorly trained biologists are focusing on the newest of the worst “invasive” species, the “Asian Common Toad.”

“Invasive Species” is bad nomenclature. Most of what hyper, reactive biologists refer to as “invasive” is intended to mean “bad.”

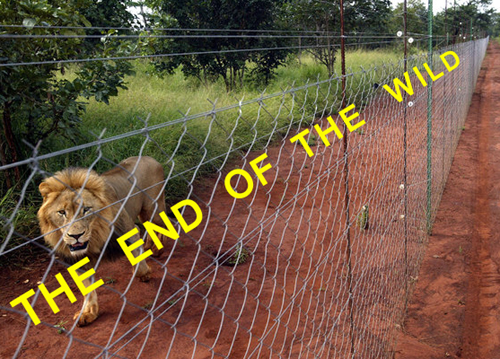

In other words, if some form of life begins to dominate an ecosystem, it’s wrong and “invasive” when its doing so perilously threatens other established species in that ecosystem.

And that’s the rub. “Perilously” is subjective and darn it, give me several examples where so-called “invasive species” have radically and lastingly altered an ecosystem.

You’ll have a very hard time. There’s no question that there are “super” specious, like the toad I discuss below that scientists worry is now threatening Madagascar, but rarely have the alerts proved as prescient as they appear when announced.

(The best example of invasive species is native Americans wiped out by the smallpox brought by European colonists, and even historically I haven’t heard much of an argument that we shouldn’t have come.)

Like my strong but nuanced argument that poaching elephants isn’t the main problem, this takes some intellectual juice to understand, and the best example right now is the alarm that conservationists are raising against the Duttaphrynus melanostictus.

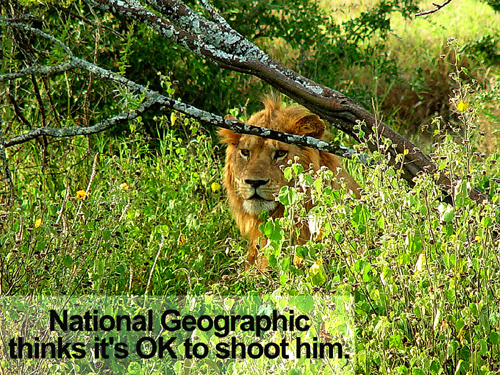

That alarm is sounded by none other than National Geographic, Nature, and pointedly, the BBC.

Nature called the event a looming “ecological disaster.”

It isn’t.

The toad is native to much of southeast Asia where it evolved. It’s toxic, so when eaten by other animals (and lots of other animals eat frogs and toads), they get sick and some die.

Discovered recently at a port in Madagascar, conservationists went ape. Madagascar is one of the most precious, unique ecosystems on earth, with up to 90% of the species found there endemic.

There’s no doubt that if left to prosper, Mr. Toad will impact Madagascar’s ecosystem. Just as the Lutherans did on the Iroquois. My point is that these alarms soliciting urgent responses to “control invasive species” are pointless, unnecessary and a scandalous misuse of resources.

“Pointless” because they don’t work. You might have been successful keeping garlic mustard out of your flower garden, but you’ll never get it out of your forest.

“Unnecessary” because mainly it’s pointless. Our failures to control invasive species have consistently and increasingly been spectacular defeats. And even if you believe that this series of defeats is reversible, would it be good for the planet?

Would the world have been better had kudzu really been eradicated? Would teepees be better than arched bell towers?

There are a couple examples in the world, the Galapagos being one, where I concede had the rat not gotten into the shed, or had been exterminated quickly enough, things would be better. But those examples are confined to rare and very small ecosystems of which the world just isn’t mostly composed.

Whereas the alarms of invasive species are overwhelmingly rung in large ecosystems, like North America.

Yet the resources allocated to these efforts, and the machismo with which it infuses the conservationist is not simply unbecoming and unscientific, it’s nonsense.

Take the toad.

The toad “invaded” Australia in the 1930s from climes north.

The fear then, as now in Madagascar, is that birds, snakes and everything precious would eat the toad and die. And many did.

Rachel Clarke and other scientists commissioned by the Australian Government to finally conclude what the toad actually did to Australia in the last century, decided that it had done really very little.

Paraphrasing the scientific report, a frog advocacy group in Australia claimed that Clarke and colleagues basically concluded that it was the “Yuk Factor” rather than any real threat to the ecosystem that drove the initial alarms.

“What’s the evidence for all this talk of ecological catastrophe and biodiversity impacts?” the organization asks then answers, “surprisingly little.”

Yes, many snakes died when eating the toads at first. That resulted in an explosion in the native frog population that was very positive for many other species as for a while there were fewer predators of them. And then, the snakes stopped eating the toads and prospered.

Yes, birds ate the toad and died. And then birds learned to eat only parts of the toad and didn’t die. And some birds, like the sacred ibis, developed an ability to eat the toad and not get sick.

In fact up to 90% of the species of some animals were initially wiped out by the toad in Australia. But then? They came back, learning or evolving how to live with them.

Madagascar is 13 times bigger than the demarcated political land and water area of the Galapagos Islands, but it is no less precious an island ecology. I think it reasonable to try to inhibit the invasion of the toad.

But there are a host of other more serious problems facing Madagascar, both ecologically and socially. If the toad is not stopped, Madagascar will not over time be considerably changed.

And it just isn’t unseemly, it’s unscientific, to scandalize what is actually the virtue of successful natural selection.

Long live the toad!