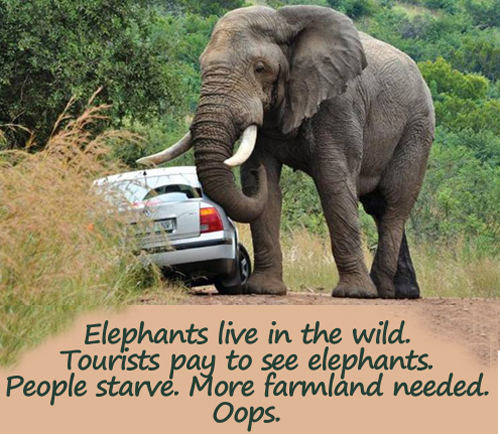

As my clients well know, I don’t approve of walking safaris anywhere in East Africa, today. Tuesday morning another tourist was killed by an elephant near Tarangire National Park.

As my clients well know, I don’t approve of walking safaris anywhere in East Africa, today. Tuesday morning another tourist was killed by an elephant near Tarangire National Park.

Thomas McAfee of San Diego was on a guided walking safari arranged by Tarangire River Camp where he was lodging.

The details are not complete, but reports of the local police report claim the incident occurred at 8 a.m., Tuesday, when McAfee and two others encountered about 50 elephant on their walk.

The report continues that the other two escaped by running away but that McAfee tripped and fell and was then killed by a charging elephant.

Tarangire River Camp is a respectable camp located just outside the park itself. Many similar excellent camps and lodges throughout sub-Saharan Africa located just outside the boundaries of a government reserve are not restrained by park regulations restricting walking. So as a sales tool they offer walking safaris.

Park regulations are strict regarding walking. Walkers must pay a special fee and must be accompanied by an armed ranger, but for the last several years in Tarangire, the main northern ranger post has declined to lead walking safaris.

I can only speculate as to why the rangers have declined to lead walking safaris, since there has been no official reason. But I suspect it’s the same reason I have: there are too many elephants, they are too stressed, and it’s too dangerous.

Be cautious, now, about unqualified criticism of Tarangire River Camp. Virtually every off-reserve camp I know in Tarangire, including my favorite, Oliver’s Camp, promotes walking safaris.

Walking safaris strike consumers as an attractive option to remaining in the car all day, and that’s understandable, and nowhere at no time have they been offered without the understanding of added risk.

The finest and most professional walking safaris in Africa are led by remarkably professional rangers in South Africa’s Kruger National Park.

And even those have had serious incidents, but notably the professional has been the one who has suffered most, and in all cases in recent memory the tourists were uninjured.

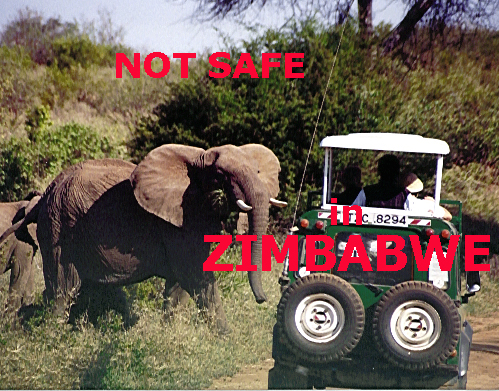

And, of course, incidents occur to vehicles, too. Most of these, in fact, are reported again in Kruger National Park, and the reason is quite simple: There are many more tourists, there, and many self-drive cars, unlike in East Africa.

In my long forty years of guiding safaris I’ve been threatened by animals, mostly elephants, dozens and dozens of times. Three times were very serious. Game viewing – anywhere in Africa – is not a walk through your local county forest preserve.

But times started to seriously change 10-15 years ago. Today the risk of an animal attack while on safari is greater than ever. The risk is easily avoided, but it requires a change in tourist behavior from what for so many years has been considered acceptable.

Don’t walk.

There are qualifications, of course. If you recognize the added risk, then there are places where that risk is less and where the professionalism and heroism of its rangers has a long history. And that’s in southern Africa, especially Kruger.

Zambia’s Luangwa Valley is also a place where walking safaris have been the featured form of game viewing for more than half century, and where the guides have avoided serious incidents for a remarkably long time.

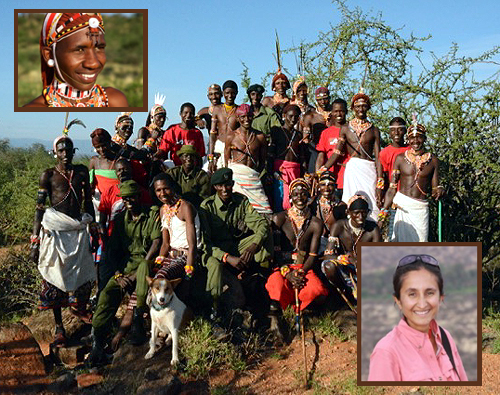

And in very remote locations, for example in Kenya’s fine Bush ‘n Beyond camps in the distant Northern Frontier, walking is probably OK.

Why is it less risky in some places? Because of different animal behaviors in different places, and because of the skill and professionalism of those who might guide you walking.

East Africa, Kenya in particular, has made great strides in the skill and professionalism of its rangers. Tanzania much less so, and Uganda is horrible. But no country in East Africa has the training or supervision that passes my requirements for a safe walk in the wild.

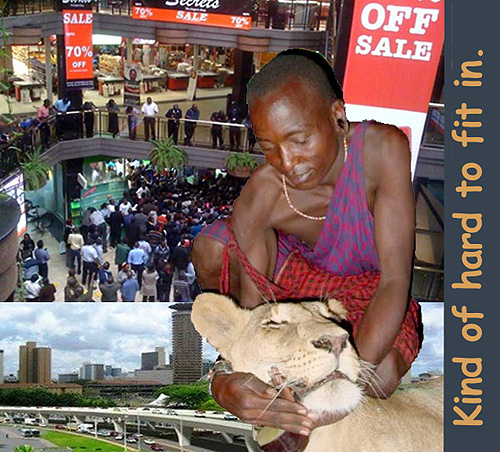

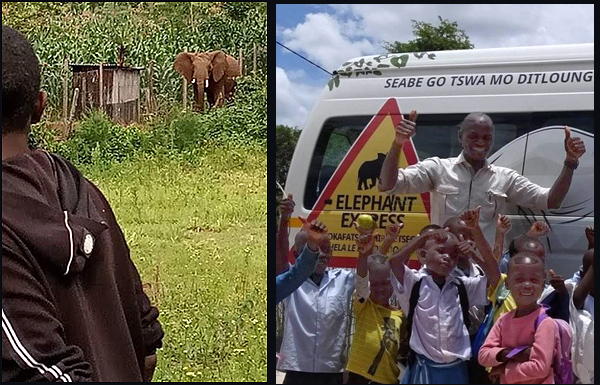

And East Africa’s wild animal population is out of control. Both in terms of simple numbers (which is a main reason I enjoy going there), and because of unusually rapid increases in human/animal conflicts that are not occurring in southern Africa.

Last night I was reading my precious first edition of Theodore Roosevelt’s Game Trails. The book is fascinating on many levels but is mostly an account of his incredibly extensive big game hunt through Kenya and Uganda in 1909.

Many, many times he and his professional hunters, Cunningham and Tarlton, approached elephant on foot, and not always just to kill them. Sometimes, just to taunt them, as when Teddy jovially reports throwing sticks and rocks at one.

To be sure Roosevelt was an accomplished hunter and sportsman, but he was careful about hunting without Cunningham or Tarlton with him. But when he accidentally “ran into” his old friend and fellow conservationist, Carl Ackley, on a private journey released from his professional hunters, he didn’t hesitate accepting Ackley’s request to kill an elephant for the New York Natural History Museum.

In those days, with the prairies and forests and velds literally saturated with game, and few if any people living anywhere, including indigenous people, the human intrusion into the animal paradise was a clear and unmitigated risk – not to the people, but to the animals!

Elephant had been hunted for ivory for centuries, and no human approached them except to kill them. It was virtually the same for anything wild, a bird as small as a wheatear was a target. Roosevelt’s arsenal contained a variety of weapons capable of downing a mole rat.

The relationship between animals and man was clear. Hunter and hunted. And man was supreme. The list of hunter injuries was great as world sportsmen defied death by challenging wild animals: Lord Delamere and Governor Jackson enjoyed showing Roosevelt their wounds from great hunts gone awry, and I definitely felt that Roosevelt tried and failed to be so heroically scarred himself.

But every animal on the veld knew that ultimately there was no contest with man. Man always, always won.

That’s changed.

Protecting animals has tamed them. And it’s important to remind ourselves that “tame” is our definition, not theirs. We have manipulated wild animals so that we can approach them more closely and enjoy them, even as they wander in the wild.

We’ve now had more than a half century of this, and that means a good two generations of elephant and far more in the lesser animals. Wild animals in African parks grow up far less afraid of man than their wild and natural behaviors would otherwise intuit.

That worked beautifully for many, many years. But about 15 years ago it became apparent there were too many wild animals too densely packed into these protected reserves in East Africa, where the most exciting and supreme game viewing occurs.

That’s logical, of course. You protect something and it will prosper. And to be sure “too many” is my own assessment and nothing more scientific than that. Reading Roosevelt it’s quite clear there were more animals then, than now, but they were spread all over the place. Roosevelt reports “zebra attacks” within the Nairobi city limits. Nowhere did he wander, even over the volcanic rock of the northern frontier, without encountering herds of animals.

But they were never as densely packed together as they are, today, in a national park.

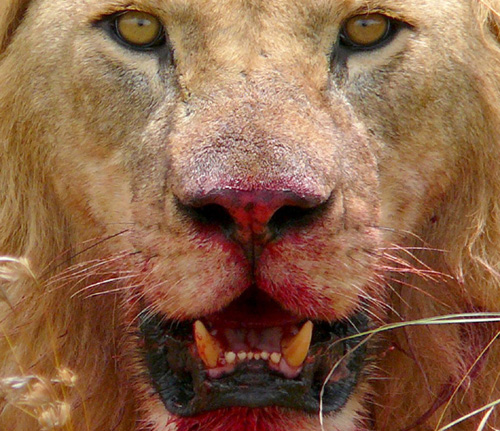

Over population has its own inherent risks. It stresses the animals as they compete for the same food sources and breeding areas. Tarangire in particular has the most serious problem, because its principal wild animal is the elephant.

Normal elephant behavior broke down in Tarangire about 15 years ago. That’s when we began to see unusually large groups of elephants (more than several hundred together at once), multiple families, feeding, breeding and moving together. That’s not natural for elephants, but it was mandated by their reduced space.

Global warming has radicalized the feeding cycles. Increased human populations on the periphery of reserves primarily pursuing farming exacerbates the human/elephant conflict.

So the tension between man and elephant increased substantially over the last 10-15 years. A terribly frightful incident on one of my own safaris in 2007, when a dear client was pinned on the ground by an elephant was the final determination I needed. (Stephen Farrand suffered only cuts and scratches after professional and quick action by one of my drivers.)

And since then the situation has been aggravated even further as unusual rains increased animal herds too fast, and as the Great Global Recession sparked increased poaching. And the poaching as I’ve often written is quite different from the corporate, helicopter, big-truck harvest poaching of the 1970s/80s.

The poaching today is generally by a small group of raiders on foot, because the value of a single tusk is so great, the small scale ad-hoc poaching proves economically worth it.

Imagine a generation of elephants, tamed to the point of putting their inquiring trunks through the top of my opened vehicles (as often happens), suddenly confronted one night by 4 or 5 men on foot trying to kill it.

Pursuit as was man’s only role in Roosevelt’s time is new to a young elephant in today’s world. Man is supposed to be that pretty admirer in a steel box. Suddenly that man is trying to kill it.

Contrary to many researchers and general mythology, elephant aren’t smart. They’re beasts, reactive, powerful and now … terribly confused.

Don’t walk among these tembo. We’ve known this for a number of years, now. We’ve been unsuccessful stopping the camps from offering the activity. It’s now your responsibility, and an easy one to embrace.

Don’t walk.

We weren’t going to tip over, at least I didn’t think so. But when our “guide” clonked out and bounced onto the rubber floor our raft of four plus him started twirling in the fizzy white water like an alka seltzer dissolving in a glass.

We weren’t going to tip over, at least I didn’t think so. But when our “guide” clonked out and bounced onto the rubber floor our raft of four plus him started twirling in the fizzy white water like an alka seltzer dissolving in a glass. Yesterday a baby seal, about the size of a small black lab,

Yesterday a baby seal, about the size of a small black lab,  Suspend your belief. I found an African charity that doesn’t boil my blood.

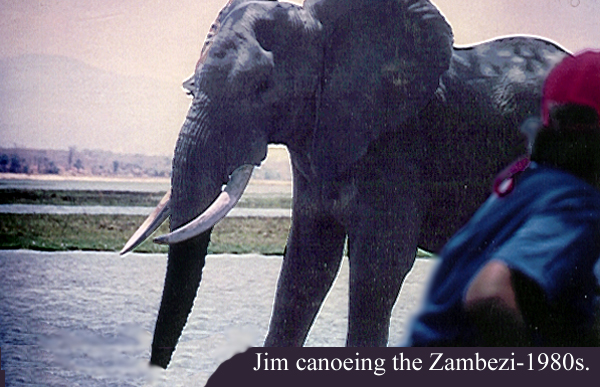

Suspend your belief. I found an African charity that doesn’t boil my blood. A Florida woman canoeing down the Zambezi nearly

A Florida woman canoeing down the Zambezi nearly