Andrew Harper’s sissy-fit earlier this year about Nairobi’s best hotel, the Norfolk, because they refused to give him an early check-in (that he didn’t pay for) was just another little annoyance of his that I usually ignore. But now my own clients are asking me to respond, so here goes.

Andrew Harper’s sissy-fit earlier this year about Nairobi’s best hotel, the Norfolk, because they refused to give him an early check-in (that he didn’t pay for) was just another little annoyance of his that I usually ignore. But now my own clients are asking me to respond, so here goes.

Bit by bit, blog by Huffington Post blog, my irritation with Andrew Harper’s remarks was never great enough to warrant a response. What I noticed was that in 2008 and 2009, when he launched big time his travel company, his critiques started to turn into infomercials.

But, you know, a lot of us (and I include myself) are travel commentators and analysts with travel companies, so there’s no lack of owners recommending themselves. But I’d put myself and many others in the good guy group, people like Rick Steves. I really think we achieve a balance despite our vested interests.

I don’t feel qualified to speak generally about Harper, but I do feel eminently qualified to say what I’m going to say based upon his recent remarks about East Africa:

Beware Andrew Harper when planning a safari to East Africa.

I often caution travelers not to embrace any single guidebook, any one internet site or any single authority or single personal referral when planning their travel, and to recognize that each may provide some insights but that each can also come bundled with inaccuracies and other flaws.

Think of it this way. If you had to tweet the absolute best time to visit your own home town, what would you say? Stutter, stumble, toil and trouble is a good sign. There’s too much to qualify.

A good analysis, travel or anything else, is careful about broad generalizations, mindful about seasons and unique conditions that might be totally off base if applied to someone traveling at a different time or in a different way.

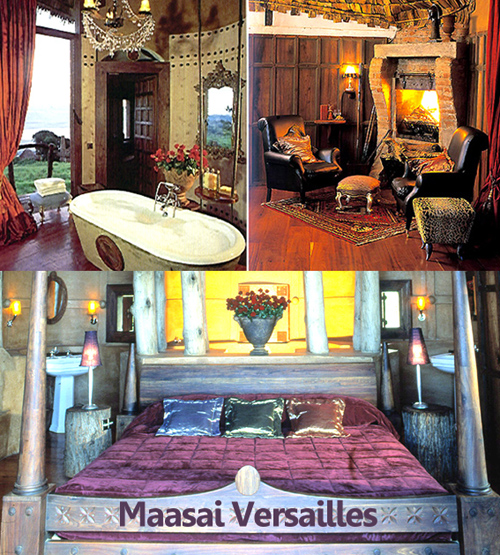

But in East Africa, Harper has lost this care. Of the nearly 1200 safari properties in East Africa, he’s reduced his recommendations to a single company, &Beyond. &Beyond’s good, don’t get me wrong. But it is rarely worth the prices they command, and in fact several of their properties are very poorly located especially for certain seasons. And there are many companies that rival or exceed their standards (Sanctuary Retreats, Lake Duluti Lodge, Bush ‘n Beyond, and some of the Cheli & Peacock properties to name but a few which quickly come to mind, and this is hardly exhaustive).

So what caused Harper to reduce this huge cornucopia of wonderful safari lodges down to the few managed by &Beyond?

I think I know. They’re the most expensive, and they treated him nicely when he last visited them.

Neither of these two reasons is inherently bad. And as I said, &Beyond is good, but clearly Harper isn’t doing his homework and more importantly, an event he himself referred to clearly outs him when it comes to any value he may now possess regarding recommendations in East Africa.

Harper went to East Africa last year and began his trip at Nairobi’s best hotel, the Norfolk. He arrived before the stated check-in, and his room wasn’t ready.

He blew a fuse. He claims that the early check-in had been guaranteed, but Fairmont does not guarantee early check-ins. What they guarantee is what most larger chains do, that the request will be put into the computer record, a sort of priority waitlist.

Harper knows this, we all do! But he simply couldn’t understand why Fairmont would deny such an important critic an early check-in.

(Perhaps it was because, as is often the case, the Norfolk is full up with Heads of State, concert pianists, billionaires and fancy journalists.)

And given what Harper’s now earning from his travel company, I can’t understand why he just didn’t prepay for the early check-in like the rest of us do (including Heads of State, concert pianists, billionaires and fancy journalists).

So he laid into the hotel, unliterally. He threw down the gauntlet and stomped away like a kid who wasn’t allowed to join the ballpark game.

He moved to, and now recommends instead of the Norfolk, Giraffe Manor for a Nairobi stay. First I must say how much I love Giraffe Manor, and what a great job Mikey Carr-Hartley has done since purchasing it several years ago. It’s a fabulous place. As are all the Carr-Hartley properties.

But it’s no substitute for the Norfolk, because of where it’s located. It may be a great addition, but it’s not in Nairobi! It’s no substitute for a good hotel in the city.

The Norfolk is in town. Giraffe Manor is out of town. At the best of times (maybe 2 a.m.) it’s still 40 minutes from town. For the rest of the day traffic can separate them by an hour. The Norfolk positions you for town activities, like the museum, shopping, people gazing, dining, etc. Giraffe Manor is a retreat from all of that.

Harper is simply way off base in his criticisms of The Norfolk. He’s more correct about the mayhem of Nairobi town, but if that’s his gripe, he shouldn’t have stayed at Giraffe Manor, either. Hit the airport and fly directly into the bush. It’s a pain getting to either of them from the airport these days.

Harper tried to list specific complaints, about plumbing and air-conditioning, for instance. He’s right on. But don’t expect you won’t incur such annoyances at every place in East Africa at some time or another, &Beyond and Giraffe Manor included.

That’s East Africa, as compared to Europe for example. It’s a reflection of constant power outages, inferior craftsmanship and materials, and bad roads. It’s a good object lesson in the difference between the standards of expectations in East Africa versus southern Africa. And in the course of an overall safari, it’s hardly noticeable and rarely happens. The fact this litany of irritations all happened to Harper during a single stay at the Norfolk is suspect.

But whether you believe me or believe Harper about the standards of the Norfolk, there’s no way anyone with half a keyboard and dial-up can’t easily prove him absolutely wrong on much of his general commentary about East Africa.

Here’s Harper’s basic introduction to East Africa, corrected with my italics as you go:

“Wildlife-viewing is generally excellent throughout the year in the Masai Mara and Ngorongoro Crater. However, game-viewing opportunities peak from January-April in the southern Serengeti and from June-October in the northern Serengeti. This variation is due to the Great Migration of several million wildebeest, zebra and gazelle. (Gazelle don’t migrate.)

…”The herds gather in the south to feed on the immense grasslands and to give birth to their young. When the food supply is exhausted (only when and because the rains stop) and the newborns are strong enough to travel (that doesn’t matter, they go whether the young are strong or not) they begin to head north and west (and northeast), passing through the Grumeti area from May-July (and a lot of other areas but &Beyond just happens to have a camp in the Grumeti area).

…”By August, (normally only about half) the herds have reached the northern Serengeti, where they cross into Kenya’s contiguous Masai Mara to enjoy its lush grazing. In November (or October (2009) or December (2010)), they begin the 200-mile (roundtrip 200-mile) trek south to the plains of the southern Serengeti, where the grass is once again lush after the seasonal rains. There the epic cycle begins anew.

…”The times to avoid in Kenya and Tanzania are the long rains. (Northern Tanzania has only ONE rainy season. Kenya and only north of the equator has two rainy seasons: long and short. Just look at the welcome sign to the Serengeti National Park which describes this on a sign about 10′ high) in April and May and the short rains in November. The rest of the year, you can typically expect cool nights and warm, sunny days broken by occasional afternoon and evening showers. (There’s been no measurable rain in the Serengeti in September or October for the last half century since good record-keeping began.)

…”In recent years, however, weather patterns have become notoriously fickle. (No cigar, buddy, not as fickle as your mounting inaccuracies.)

OK, OK, there’s some nit picking above, and, in fact, that’s my problem. Take any one paragraph, and it will pass over my bitten lip. Take any one blog about East Africa, and it’s foolish and silly but not worth the time to answer. I even passed on the Norfolk blog last December.

Believe it or not, I even passed on his February blog about the Serengeti, carried in the Huffington Post about the Serengeti highway.

The post is crammed with dated ideas, wrong facts and poorer generalities. But it was the final paragraph that really ticked me off:

“Of course, African people have a right to development. But the Serengeti is Nature’s equivalent to Chartres Cathedral. And if it is not possible to preserve the world’s greatest national park, then what, ultimately, will remain? “

This patronizing, slimy (is it racist?), egocentric condescending nonsense begs all sorts of really important questions many of us have been trying to deal with for years. Harper has proved he has no capacity to judge the “world’s greatest national park” any has moved into vendetta mode.

But I let it sit until recently a client contacted me and asked what I thought, since I still recommend the Norfolk.

What we have here is a man whose ego was pricked by a global hotel chain, Fairmont, and who has lost his cool. Honest critique has been replaced with … infomercials.

I’m not alone, by the way. You can go to the blogs and forums of excellent traveler sites such as Gallivanter, Inworldguide and Flyers.

Here’s one short one that sums them all up:

From BLG on Flyer’s:

“As far as the Harper services are concerned, I was a member for many years and I dropped my membership — didn’t feel like I was getting much that I couldn’t find for myself online, and I was not a fan of their in-house travel agency… I kind of feel like those services have been somewhat obsoleted by the plethora of great internet sites.”

Beware a crusader, especially one crusading for himself.

I was supposed to be in Paris with my wife celebrating our 50th anniversary. I’m in Dublin where I’ll be writing more about this interesting, unexpected journey due to Covid in later days. But today I just gotta write about Marriott!

I was supposed to be in Paris with my wife celebrating our 50th anniversary. I’m in Dublin where I’ll be writing more about this interesting, unexpected journey due to Covid in later days. But today I just gotta write about Marriott! What’s the greatest risk to an international traveler right now? Obviously, Covid, but NOT for the reason you think! A vaccinated traveler is very unlikely to get sick from Covid. More vaccinated travelers are going to get hurt and some die from slipping on the stairs of the jetway than from Covid. More vaccinated travelers headed into wild jungles (who are taking malaria pills) will still get sick from malaria than from Covid.

What’s the greatest risk to an international traveler right now? Obviously, Covid, but NOT for the reason you think! A vaccinated traveler is very unlikely to get sick from Covid. More vaccinated travelers are going to get hurt and some die from slipping on the stairs of the jetway than from Covid. More vaccinated travelers headed into wild jungles (who are taking malaria pills) will still get sick from malaria than from Covid. The carnage of African safari companies grows like a dry season wildfire. Distant Serengeti grasslands are lit with flames of desperation. The dead grasses fueling this destruction are the charities proffered to safari customers as a benefit of their bookings.

The carnage of African safari companies grows like a dry season wildfire. Distant Serengeti grasslands are lit with flames of desperation. The dead grasses fueling this destruction are the charities proffered to safari customers as a benefit of their bookings. I’m betting that a vaccine will be ready by the first of the year and that Kenya, South Africa and a number of other sub-Saharan countries will require all travelers to prove they are vaccinated in order to gain entry.

I’m betting that a vaccine will be ready by the first of the year and that Kenya, South Africa and a number of other sub-Saharan countries will require all travelers to prove they are vaccinated in order to gain entry.