Why do so many safari travelers want to “see a village?” A Paris exhibition may help explain the ugly urge of many travelers to witness depravity.

Why do so many safari travelers want to “see a village?” A Paris exhibition may help explain the ugly urge of many travelers to witness depravity.

The market for village visits is so strong that even today, when traditional villages just don’t exist, they are being reconstructed, and thousands of visitors return from Africa every day believing they have seen “an African village” in exactly the same way conservatives leave church each Sunday believing Satan is a Muslim.

In the early boom days of photography safari travel (1960s and 1970s) “visiting a village” was an absolutely essential ingredient of any trip and I admit having arranged hundreds. “The Invention of Human Zoos” is a brilliant exhibition in the new Quai Branly museum that helped me to understand why.

“Act I” of the exhibition chronicles the excitement and amazement of Europeans who “discovered” such new and different peoples around the world starting in the 15th century. This “otherness,” as the exhibit calls it, was a driving force for early exploration.

Brazilian Tupinambas prostrating before Henri II in Rouen in 1550, Siamese twins in the Court of Versailles in 1686, Inuits overdressed before Frederik II in Copenhagen in 1654, and the famous “Noble Savage” Omai that Captain Cook brought to England from Tahiti in 1774 were some of the first and most famous.

There was no community exhibitionism in these early moments. It was just exhilaration at finding something so different from yourself! I hope this at least partly explains myself as a young “explorer” anxious to show clients African villages in the early days.

Omai was real; Kenyan villages in the Northern Frontier were real in the 1970s.

As the age of exploration matured, “Act II” of the exhibit details how this surprise at “otherness” grows defensive. Surprise doesn’t last. The reality sets in that this “otherness” isn’t very pleasing, because it’s filled with misery. But what to do? Go out and civilize the world when we’ve got so many problems to deal with here at home?

So “otherness” becomes “wrong” or “bad” or “evil.”

Circuses, traveling villages and freak shows worldwide marketed this rationalization by “blurring the difference between the deformed and the foreign.” Soon “physical, psychological and geographical abnormalities” sold tickets.

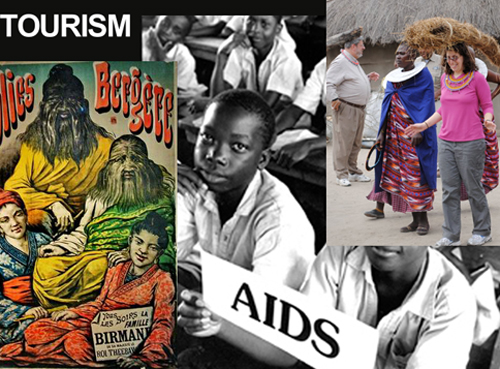

By the 1980s and certainly 1990s Africa was developing as fast as information technology. Primitive people weren’t primitive, anymore. But primitive and “savage” and “diseased” and “deprived” were the “physical, psychological and geographical abnormalities” that could still get tourists to pay.

So easily predicted these “villages” suddenly existed right next to very swank tourist lodges and camps. “Maasai villages” which in their original form never existed longer than the rains which fell on them for a single season, suddenly were in place for decades.

“Act III” of the exhibit describes the Crystal Palace, Barnum and Bailey, Paris Folies Bergères and Berlin’s Panoptikum where visitors are thrilled by “acts of savageness” from supposed aboriginals, ‘lip-plate women’, Amazons, snake charmers, Japanese tightrope walkers and oriental belly dancers, all of whom were “made-up savages” – professional actors, not real individuals.

Exactly as in Africa, today.

One of the real catastrophes this produces in Africa is that real depravity is created where it would otherwise not exist. When traditional villages moved regularly, as most did and certainly the Maasai and Samburu always did in the early days, opportunities for disease were lessened.

Imagine today’s so-called “Maasai village” outside Samburu Lodge or Serena Lodge after one year, two years, five years and then ten years without adequate septic systems.

(The final “Act IV” is more oblique and less relevant to Africa, I think. The extreme circus and freak show begins to merge “otherness” with physical abnormality. Indeed, the rise of Felini may be an important phenomenon worth examining, but its relevance to visiting a village in Africa is slight.)

There is, however, an Act IV today in Africa.

There is this inexplicable, basest urge by travelers to Africa to see “primitive” and “depraved” and the market reigns with these reconstructed villages more than ever. If there weren’t tourists paying to see them, they wouldn’t be there.

Thousands of safari travelers, egged on even more by immoral tour companies, regularly “want to see a village.”

What do travelers really mean when they ask for that? What they mean is that they want to see poverty, disease and depravation. In a nutshell, suffering. First off, why the hell would you want to see something like that? To disabuse yourself that it might not be true?

Alas the danger with that generous presumption.

Any half educated idiot walking into one of these should be able to tell by the facility of languages the “chief” commands, the perfect and untattered costuming, rushed routine and proforma narratives, that this is a show, not a lifestyle.

So that at least subconsciously the visitor can return at least subconsciously unconvinced that suffering exists. Or has to. Or that he has any responsibility to end it.

I was absolutely incensed recently by the “Mad Travelers” Kevin Revolinsk’s “Visit to a Maasai Village”. It’s below disgusting; it’s despicable. Yet this is a popular guy, widely published and validated by much of the established media like the New York Times and National Geographic.

And I’m sure there are many more examples as Revolting as Revolinsk.

Don’t be fooled, traveler. The misery is there, beyond your imagination. But it doesn’t exist in the flies unnecessarily flitting on the poor little kid’s face, but with the internal pain of the mother who plasters a bit of cow dung on her child’s head just before the tourists arrive… because she can’t get a job in the city.

Let’s end Act IV.

Last spring my favorite African journalist of all time (I actually think he outdid Stanley) published a memoir, Love-Africa, that so disappointed me I’ve taken quite a long time to think about before writing this.

Last spring my favorite African journalist of all time (I actually think he outdid Stanley) published a memoir, Love-Africa, that so disappointed me I’ve taken quite a long time to think about before writing this.