The short-term, visible effects of climate change on equatorial Africa are destructive to human populations but seem to be less damaging to overall species survival than elsewhere in the world.

The short-term, visible effects of climate change on equatorial Africa are destructive to human populations but seem to be less damaging to overall species survival than elsewhere in the world.

Not sure that’s good news, but recent reports from such places as the Seychelles on current equatorial seabird populations suggests they are doing much better than seabirds in northern and southern climes.

Seabirds provide good evidence for relatively short-term effects of climate change. This is because they are most closely associated to the most effected natural phenomenon on earth, the sea temperature.

Worldwide as we would expect, therefore, seabird populations are in a steep decline. In fact, of 346 seabird families almost a third (98) are “globally threatened,” an IUCN term suggesting that intervention will be needed soon to stop extinction.

The most critical of these declines is in the northern hemisphere. Puffin populations, for example, in Maine and tern populations in northern Britain are in currently very critical conditions.

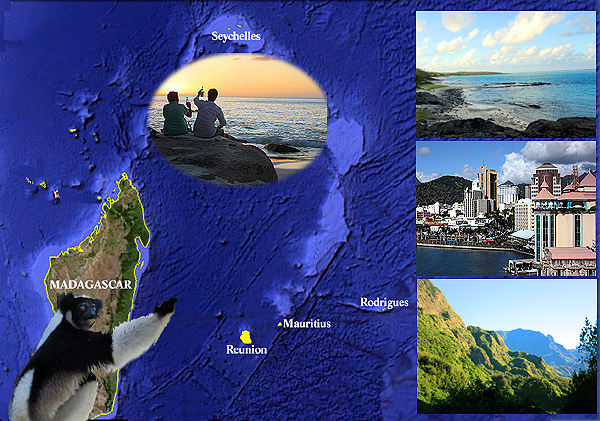

The opposite of these declines — although it’s hardly robust growth — are the seabirds found in the equatorial regions, and in Africa the Seychelles provides an excellent place to study them.

This August count of the white-tailed tropicbird and other seabirds that nest in the Seychelles was encouraging, although the study has yet to be published.

The group performing the study did release an interesting single statistic, though, that 57% of the nesting population survives. This is the most critical period in the life cycle of any bird, because once fledged survivability increases dramatically.

It’s also particularly interesting for the tropicbird, which like many seabirds doesn’t actually build a nest. With feet incapable of balancing the bird (they are designed for swimming and flying), the bird must nest on the ground.

Seabirds choose island nesting sites that are as safe from predation as possible. In Hawaii, for example, the white-tailed tropicbird nests on high cliffs. In the Seychelles, where the islands are mostly predator-free, it nests right on the ground.

This dynamic that’s possibly being clarified by how seabirds are adjusting to rapid climate change, gives us a good insight into the workings of natural selection.

Given enough time, environmental changes allow species to evolve and reposition themselves, and as a general theory, increase. As slow change allows for niche exploration, more specialized species arise.

But when change happens as unnaturally fast as it’s occurring, today, the normal mechanics of natural selection are compromised. Water temperatures are just increasing too fast for the northern hemisphere puffin to adapt or be replaced by other species. So instead, it just dies out with nothing replacing it.

Whereas in the equatorial belt the decline is not as dramatic. Basically, warmer is better than colder for our petri dish of life on earth. But at the fringes of ecological system, the great norths and the great souths where our life forms have specially adapted to colder temperatures, a rapid warmer is dangerous.

In the equatorial regions, it’s almost ho-hum.

At least until some threshold of warmth is reached, of course. But thanks to the Seychelles field workers, we know it isn’t happening, yet.