Go get ‘um DeRisi. And Yeh upstages the NFL season opener with an end-run over the Apicoplast! Yes! The battle against malaria, the first offense that might just actually win, has begun!

Go get ‘um DeRisi. And Yeh upstages the NFL season opener with an end-run over the Apicoplast! Yes! The battle against malaria, the first offense that might just actually win, has begun!

Here it is, are you ready?

“Chemical Rescue of Malaria Parasites Lacking an Apicoplast Defines Organelle Function in Blood-Stage Plasmodium falciparum”

For those of you who think you might have a scintilla of a chance of understanding this, it would behoove you to go to the Home Page of “PLOS” in which this article appears.

This is such an incredibly important scientific breakthrough, that this normally complex scientific journal has rearranged its home page since publication yesterday to try to help us lay folk understand.

So will I try, too.

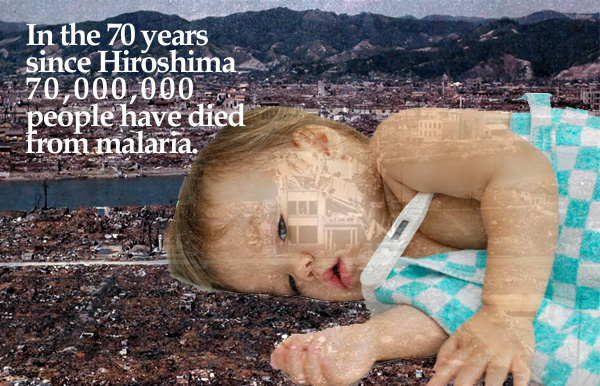

Malaria is the worst parasitic disease of humans today, and as far as we know, has existed for the longest time of any large scale endemic human parasitic disease.

Its effects are devastating. It’s a story of one organism, the malaria parasite, beating up another, human beings.

My own involvement with malaria has been intense. I know I’ve had it twice, once near death, but I’ve probably had it more often than that. My wife was very sick with it once. Early, bad medications helped partially ruin the sight in my right eye.

I’ve held babies in Africa dying of malaria. I’ve had countless employees sick with it.

Probably every single employee manager for me in Africa has had a close relative, like a child, die of malaria.

I’ve had a dozen or so clients who came home with it from safari and were misdiagnosed and then mistreated. I’ve had more clients who seemed to go crazy when using incorrect malarial prophylactics.

Malaria has beaten us up.

I would love to live to see the day when the fight turns. And it may actually happen!

I’m no scientist and most of my understanding comes not from PLOS’ wonderful attempt at a plebian home page, but from the even simpler attempts at explanation.

The best I’ve found comes from the researchers’ own university, Stanford.

It all has to do with the apicoplast!

Well, that’s it, then!

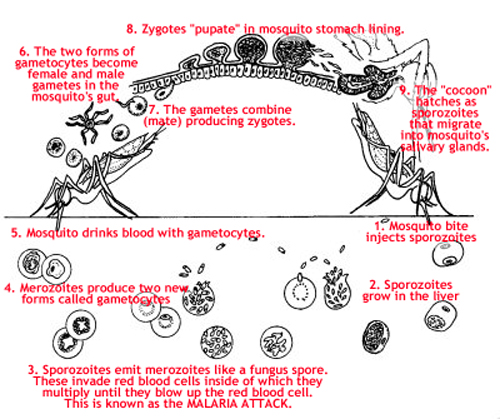

Sort of. Over the last decade, it was discovered that when the malaria is actually in the human blood stream, it swims merrily around with a little “organelle” inside it called an apicoplast. Organelles are sort of like adopted organs of a single-cell organism that were somehow taken from some other single-cell organism.

A long, long time ago. Apparently this happened millions and millions of years ago. We know this from the genetic structure of malaria. As man was increasing his brain size and creating tools to conquer the planet, the joker malaria was searching madly for a better offense.

Somewhere out there, it found an apicoplast and consumed it into itself forever and that was apparently when it became deadly to man.

But we didn’t know why. For the last decade a number of researchers have been trying to create drugs that would specifically target the apicoplast like a nano drone, but to no avail.

We know there have been dozens of drugs starting with quinine that work for a time against malaria. But the parasite, like most diseases, reproduces so quickly that it’s always just a matter of time until natural selection filters out the progeny resistant to the drug, and then the drug becomes useless.

That’s how I got my first case of malaria. We didn’t know it at the time, but the so-called preventative drug was no longer preventative.

But if we could find a drug that specifically targeted the apicoplast? Whoa. That’s like trying to fashion a bullet that doesn’t just hit the bull’s eye, but the right milliquadrant molecule of the bull’s eye.

Struck out on that one.

Alas, genetic research to the rescue. Why not bioengineer a malaria parasite without an apicoplast? They did. But so what?

You can’t exactly go around the world and replace every malaria parasite that’s in someone’s liver with a bioengineered non-apicoplastic parasite and suddenly make them better.

And you’d have to bioengineer your malaria non-apicoplastic guy to be stronger and better than his original cousin, so he could eventually prevail over his weaker apicoplastic cousin.

Oops. Maybe then you’d create a super malaria parasite that with all its history of clever evolution might something else terribly do.

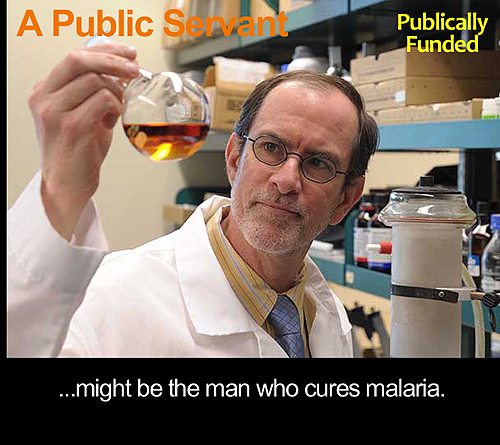

What Ellen Reh and Joseph DeRisi of Stanford did was study exactly what the apicoplast does for our little malaria parasite. And this is the discovery that will get them the Noble Prize.

It creates a single chemical, IPP for short, that is essential to the parasite. Without IPP, the parasite dies.

So what good is that? You can’t go all around the world with microsyringes and remove the IPP from every malevolent little parasite, can you?

No, of course not. But guess what? This IPP doesn’t only keep the parasite alive, it’s also the arsenal that attacks man.

Now a little secondary lesson on vaccines. You know the difference between “live vaccines” and “dead vaccines” and how the live polio vaccine wasn’t such a good idea in the 1950s.

Nor would a live malaria vaccine be any better. Although scientists have tried very hard, no vaccine they’ve produced works quickly enough that the body develops a defense against it before the vaccine prevails and makes the body sick.

So if we engineer millions and billions of malaria parasites without their apicoplast (which Yeh and DeRisi have already done), and though they die remain organic and whole long enough that our body would recognize them as the devils they once were….

Yes, the way a dead vaccine works. The human body then miraculously engineers all these micro molecular weapons that stay in the body long after the freak bioengineered dead non-apicoplastic malaria that provoked the human arsenal has been discarded.

So … that … maybe, when a real apicoplastic malaria sneaks in.. And it doesn’t look all that different from its freak dead cousin that was there a while ago … well, maybe, then:

ZAP!

The malaria vaccine is continuing good news in the battle against disease in Africa, but it’s not a cause for great celebration. I’m a bit peeved, in fact, with the PR-rollout of Mosquirix by GlaxoSmithKline which strikes me more as an attempt by the pharma to remain relevant after the failure of its Sanofi–GSK Covid vaccine.

The malaria vaccine is continuing good news in the battle against disease in Africa, but it’s not a cause for great celebration. I’m a bit peeved, in fact, with the PR-rollout of Mosquirix by GlaxoSmithKline which strikes me more as an attempt by the pharma to remain relevant after the failure of its Sanofi–GSK Covid vaccine.  What’s the greatest risk to an international traveler right now? Obviously, Covid, but NOT for the reason you think! A vaccinated traveler is very unlikely to get sick from Covid. More vaccinated travelers are going to get hurt and some die from slipping on the stairs of the jetway than from Covid. More vaccinated travelers headed into wild jungles (who are taking malaria pills) will still get sick from malaria than from Covid.

What’s the greatest risk to an international traveler right now? Obviously, Covid, but NOT for the reason you think! A vaccinated traveler is very unlikely to get sick from Covid. More vaccinated travelers are going to get hurt and some die from slipping on the stairs of the jetway than from Covid. More vaccinated travelers headed into wild jungles (who are taking malaria pills) will still get sick from malaria than from Covid. I know something about chloroquine. It was the reason I first got malaria.

I know something about chloroquine. It was the reason I first got malaria. A breakthrough in eradicating the world’s worst and most onerous disease has set the scientific and conservation worlds into a maddened dither. Why on earth is everyone so concerned that the disease we’ve been fighting for centuries might at last found its master?

A breakthrough in eradicating the world’s worst and most onerous disease has set the scientific and conservation worlds into a maddened dither. Why on earth is everyone so concerned that the disease we’ve been fighting for centuries might at last found its master? Sorry I missed yesterday’s blog. I had malaria.

Sorry I missed yesterday’s blog. I had malaria. Today is the World’s Poor Day. Oh, sorry, I mean

Today is the World’s Poor Day. Oh, sorry, I mean