Scientists in Africa are criticizing scientists in the U.S. for taking Swaziland elephants out of the country and putting them in U.S. zoos.

And in just the last few days, field scientists in the South Sudan have discovered new elephant families, and the rarer kind to boot!

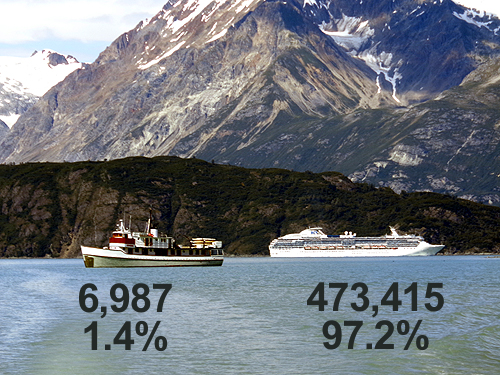

For the last number of decades it’s unusual that U.S. zoos populate any of their larger stock from wild, foreign lands. Three elephants were imported from a circus-like “elephant ride” operations in Botswana to the Pittsburgh zoo, but the brilliance of the world zoos’ “SSP” (Species Survival Program) powered by an increasing sophistication of DNA technology has allowed world zoos to create healthy and sustainable animal populations simply by exchanging them between one another.

In fact, it’s ironic that as lion populations decline by some studies as quickly as elephants, some zoos around the world are laboring with the notion of euthanizing lion, because there are so many in the captive population.

Captive elephants, though, are quite a different story from lions. Breeding takes longer and is nowhere near as successful in captive populations as with the promiscuous cat. The last several decades has seen a decline in captive elephant population as many zoos retool to become more humane and eFriendly to a public increasingly sensitive to animal rights.

It takes a much larger space, many more staff and much more exceptional husbandry to display elephants than lions.

So as the plight of elephants in the public media grows, the zoo world understandably becomes involved.

More than a year ago the Kingdom of Swaziland – not exactly your model for animal conservation – announced that it was going to cull 18 of its remaining three dozen elephants because, well, they were getting in the way.

Although the Kingdom’s official explanation through a family-run parastatal that’s in charge of its wildlife was more serious, claiming that the elephants were encroaching on habitat that would be better served protecting wild rhino, few believe them.

Nonetheless, the threat to cull is real. So three American zoos stepped in and offered to bring those elephant into the captive American population. Whether a marriage made in heaven or constructed behind-the-scenes, refreshing the captive elephant gene pool with the Swazi individuals would certainly make it healthier and longer lasting.

Problem is that virtually every field scientist in Africa I’ve surveyed is against the importation by the Dallas, Wichita and Omaha zoos.

Within weeks of the announced deal the person often cited as the world’s most experienced elephant field researcher, Cynthia Moss, gathered 80 other very respected field scientists working in Africa to agree on a “Statement of Swaziland” that bitingly disapproves of the transfer.

To get two scientists to agree on anything in Africa is a phenomenal feat. The statement is an extremely powerful indictment of the American zoo proposal.

“Certainly, this proposal will not provide any conservation benefit in the U.S. or Swaziland,” the statement concludes.

It’s now been about a year since the deal was announced. An expected hurdle that advocates of the deal had been working on, the restrictions of the CITES treaty, now grows increasingly problematic as public outcry grows.

NatGeo, Born Free, the Conservation Action Trust, and numerous other nonzoo affiliated conservation organizations are either mildly or solidly against the deal.

My good friend and Cleveland Zoo Director Emeritus, Steve Taylor, says he remains firmly behind the deal, because it has a good chance of giving the current captive elephant population “100 years of sustainability.”

If you believe the wild elephant population will not be sustained for a hundred years, then this makes sense. If you believe the wild elephant population is in imminent peril (which I don’t) it also makes sense.

But I think what is happening is that the hyperbole and rhetoric of the last few years of the demise of the elephant is producing an unfortunate counter reaction.

As often happens to exaggerated claims as evidence mounts against them, the public often goes rocketing off too far in the opposite direction.

Moss collection of field scientists “statement” did not address the very important genetic question of the captive population except with a convoluted reference to a position paper by the IUCN SSC Specialist Group for Africa which argued that importation of wild elephants into the captive population won’t help their sustainability.

But that 2003 statement came from an organization with exclusive interest in wild populations and habitats, before enhanced DNA technology, and well before the current brouhaha about elephant extinction.

While the IUCN may be the gold standard in determining species taxonomy and demographics, it is rarely involved in actual promotion of conservation policies.

Meanwhile back on the ranch, positive news about elephants has just been reported in the South Sudan where the much rarer subspecies of forest elephant has just been discovered by scientists from Bucknell University.

The discovery occurred in a part of Africa that New York Times veteran African war correspondent Jeffrey Gettleman called Africa’s perpetual war zone.

So despite poaching and wars and scientist fights, some good news.

Unfortunately, elephants have been removed from the inspection of science and thrust into the circus of the media. Hardly a year ago they were going out like a flickering candle. Today, the rarest of them pops up in a war zone.

Until the western public’s calibration of the dangers faced by African wildlife finds some measure of truth, we’ll never know who to trust: American zoos, Swazi authorities or African field scientists?