Invisible Children has produced a viral YouTube video that is dangerous. Like other U.S. organizations embracing an African cause they exploit part truths to make a buck.

Invisible Children has produced a viral YouTube video that is dangerous. Like other U.S. organizations embracing an African cause they exploit part truths to make a buck.

My young hero, Conor Godfrey, wrote an incredibly balanced and unemotional blog about this that you must reread to understand the facts of the case. That way I can just continue screaming in good conscience.

I’ve written disparagingly about Invisible Children before. Among their most outlandish accomplishments was accepting money from naive high schools in America’s heartland for a cause that no longer existed. IC did this by teasing emotions and grossly ignoring details.

IC’s raison d’etre is to tell the stories of child soldiers who played such unspeakable rolls in mostly Uganda and The Congo in the 1990s, while under the control of a still wanted fugitive, Joseph Kony. That’s true.

But when the Windsor Colorado high school (and presumably others, too) raised money for the effort at the behest of IC, the cause was already over. There have been no child soldiers or Joseph Konys or Joseph Kony wanabees in Uganda since 2006.

IC’s response was to change its website slightly and go on accepting money from lots of naive high schoolers, much less pensioned widows and disabled truck drivers. The teachers, administrators and even local newspaper reporters in Windsor refused to comment on my blog or even talk to me about it.

I am so incensed by this exploitation, and watching the video that’s gone viral on YouTube makes my blood boil. IC is continuing its false cause campaign by generalizing to the point that details be damned!

Of course we all care about children! Can’t criticize the palsy filmmaker Jason Russell for spending two minutes at the beginning of the video showing baby pictures of his son, followed by a minute segment showing the birth of a very white child. Warm us up, so to speak.

The entire video is so tweaked with these generalized but irrelevant emotive gimmicks that I feel I’m watching a drug company commercial on the evening news. Russell’s honey coated commentary belies a very disturbed psyche, someone whose deepest soul is daring pushback against a blind evangelical drive to tell a story … that really isn’t.

The true story, as Conor reviews above, actually has parts with happy endings, not particularly conducive to a charity campaign.

Joseph Kony is a fugitive, probably in the Central African Republic (CAR), not Uganda. He hasn’t been there since he was roundly defeated by the Ugandan military in 2006.

We should presume Kony continues his sadistic ways of conscripting, drugging and brainwashing young children to be killers – the heart and soul of IC’s craven drive for wealth and fame. But we have little hard evidence of a scale anywhere near his robust days in Uganda.

Voice of America reported in March of his redeveloping presence in The Congo near the CAR. But as one of my all-time favorite journalists, New York Times reporter Jeffrey Gettleman explains in his March essay in the New York Review of Books, Kony is involved in only one of “dozens of small-scale, dirty wars” that while absolutely terrible doesn’t begin to achieve the magnitude of murder and destruction Kony leveled on Uganda in the 1990s.

But if IC owns up to the facts it might kill the golden goose.

The warehouse of emotion that IC has harvested from an unwitting American population, much less its cash charity, corrodes to the core the intention of every good person donating to it.

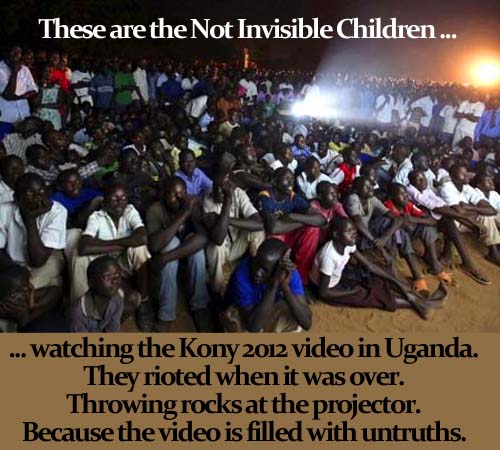

IC is especially being denounced in Uganda, where it all began. Ugandans are proud that they’ve routed Kony, so when the video was shown there last month it nearly caused a riot.

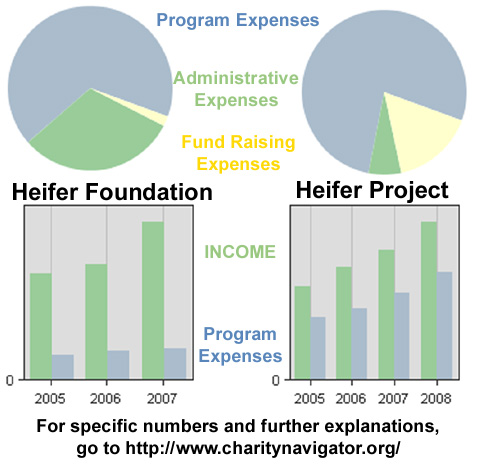

The excellent blog, Upworthy, tells a more sinister fiscal tale about IC in the recent post, “Share This Instead of the New Kony Video”:

IC recently accepted $750,000 from the National Christian Foundation (NCF). The NCF designed then funded the campaign in Uganda to pass a “Kill the Gays Bill” about which I and so many others have written. NCF gives other big sums of money to “The Call” which sends youthful missionaries into “dominions of darkness” like San Francisco to retrieve gays from their purgatory.

Also on NCF’s big recipient list with IC is the Family Research Council and The Fellowship. These mega right-wing organizations are well known and so dangerous, not just to Uganda but America. Just spend a few minutes on Google to build your Darth Vader tome.

This is the recipient pool that IC shares. And its message, methods and racist causes are also the same.

Weep when you watch the video. But let the tears dry before besmirching a check. You’ll realize that your clenched fist is packaged for IC not Kony.