Africans are bristling but resigned to the current Clinton safari the same way I’m resigned to a President Hillary. What a dreary day.

Africans are bristling but resigned to the current Clinton safari the same way I’m resigned to a President Hillary. What a dreary day.

The Clinton clan minus Hillary is currently on a 9-day African tour to Kenya, Tanzania, Liberia and Morocco, and they are not getting the reception they had expected.

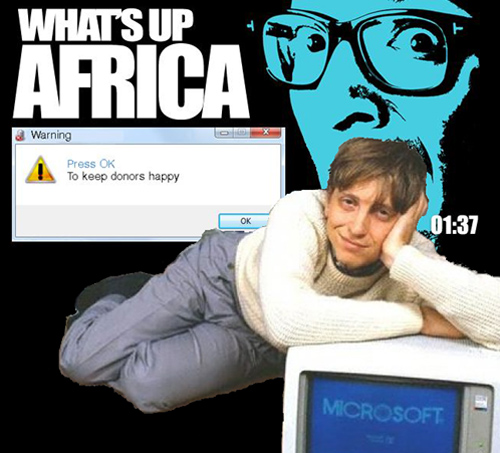

Like the Bill Gates Foundation, the Clinton Foundation is highly vested in Africa, and so you would think it natural that from time to time the principals would come here.

“O, fellow benighted Africans! Gaze down at the bleeps emanating from your electronic device – a device powered by the marvelous coltan mined on your land. Can you not see the newsflash? Dignitaries, Big Names indeed, have come to our continent in order to help us help them help us,” famous African filmmaker and writer, Richard Poplak, wrote yesterday.

Poplak is white, South African born bred and nurtured, and like most of the intellectuals of all colors on the continent, not particularly happy with the Clintons.

Poplak continues:

“…the Grand Priests of the Clinton Foundation, the givers who give almost as good as they get, [have come] to sniff the cow dung burning in rustic villages, to pat the heads of the doe-eyed children they have kept safe from brand name infectious diseases.

“O, African, behold Chelsea Clinton, future presidential candidate of the Democratic Party… Lynn Forester de Rothschild, the billionaire boss of E.L. Rothschild… [billionaires] Jay and Mindy Jacobs are here!

“O, but Africans, there is more. No one less than Hadeel Ibrahim is here! The daughter of Sudanese-British billionaire mobile phone philanthropist Mo, Hadeel Ibrahim is a great friend of Chelsea’s, and they apparently spent a wonderful thanksgiving together at the Clinton pile in Chappaqua. All has been forgiven since Bill Clinton Cruise Missiled the Al-Shifa pharmaceutical factory in 1998.”

Like the Bill Gates Foundation, the Clinton Foundation is even more heavily invested in Africa. I believe this is Bill’s penance for having “made a mistake” (his own words) when he ordered his United Nations ambassador to vote against increasing the Canadian UN force that could have stopped the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

The problem is, Clinton has piled one mistake on another in Africa. He hugely empowered Ugandan president Museveni when all of us knew that was a mistake. Museveni is now one of Africa’s great dictators, the author of the “kill the gays” bill.

Poplak continues:

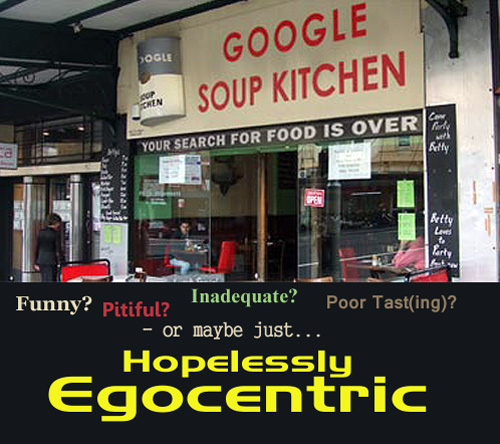

“Along for the ride are many other Clinton Foundation donors… professional philanthropists, Silicon Valley whizz-kids and generally outstanding humans. The safari …will culminate in a dazzling conference in Marrakesh, presided over by that famous empowerer of women and long-time Foundation supporter, the King of Morocco.

“And it is equally churlish to think of the Clinton Foundation as a giant corrupt money suck akin to the worst African banana republics: … [The fact that] Bill Clinton seems to have helped a Canadian mining magnate hand over 20% of America’s uranium resources to the Russians while Hillary was leading the state department, does not ipso facto make the outfit rotten.”

But she would be the first woman president!

“And what does it matter to you, O African, that tens of millions of dollars have flowed into Clinton pockets from women’s empowerment centres like the UAE and Saudi Arabia, either for speaking fees or for donations?

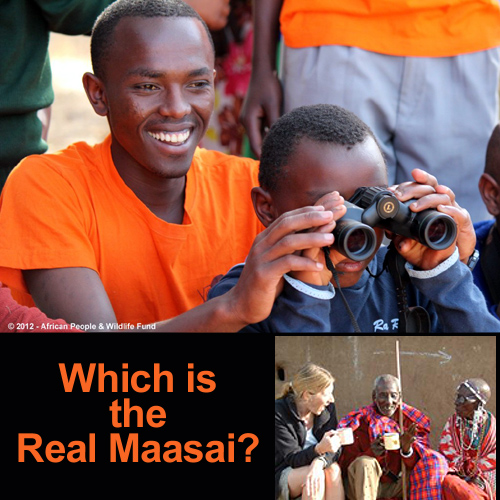

“… it may be tempting …to imagine that the Clintons and their Foundationites are using the continent as a theatre set, and we Africans as drooling extras… It is tempting to say that this is all about big money and real politick, because Bill and Hillary Clinton, along with their Chelsea clone, serve power for power’s sake.

“You might wish to say that this all seems so garish and ghastly, millions of dollars blown by a 0.1% cabal on swanning about the continent, billions of the world’s wealth zipping over the African savannah in a legions of Lear Jets.

“But you would just be sour to think that way. Ungrateful. When the beautiful waxed SUVs zip into your village and you smell the $1,500 anti-aging cream on the frozen faces of these Kings, these Gods, remember to thank them with the appropriate deference. Remember to bow and scrape.

“If we don’t look the part, then they don’t get the money.”