Eight-year olds – lots of them – are dying agonizing deaths in Tanzania as the government and world turn a blind eye to child gold-mining.

Eight-year olds – lots of them – are dying agonizing deaths in Tanzania as the government and world turn a blind eye to child gold-mining.

This morning Human Rights Watch issued its long anticipated report on child mining in Tanzania.

Not that we didn’t know there were “thousands” of children involved, that the Tanzanian government has consistently denied a problem, or that unacceptable levels of toxic wastes equal to biochemical weaponry cause the most grief.

I wrote myself about this less than two weeks ago.

I guess we just needed this respectable report to figure out what to do. So what do we do, now, we who are not Tanzanians but love Tanzania no less than children anywhere … what can we do?

Start a petition? Contact your tone-deaf congressmen? Divest yourself of multinationals in Tanzanian mining (see below)? Increase your black-hole tithing? Support NGOs working for better alternatives?

Or own up to the reality that nothing will stop this defamation of humanity except serious redistribution of wealth.

My reading of the 96-page report is a horrifying recognition that the increasing gap between rich and poor is the real cause of this calamity.

How the hell can you stop a child who is almost always sick with a cold and diarrhea who knows that a pill she can buy for a quarter will make her feel better, from sticking her hands into a plate of liquid mercury, when she knows that there’s a chance of 1 in 6 of pulling out $10?

She knows the mercury is bad. She knows that doing this enough times will make her unendingly sick. But she’s sick, now! She wants to get better!

What on earth will you tell a kid who has no father, whose mother is a prostitute for wealthier miners, who at best eats one meal of porridge a day?

Most of the child laborers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they used their earnings “for basic necessities such as food, rent, clothes, and school supplies such as exercise books, pens, and uniforms.”

The incredible horror stories in the report of children getting sick from chemicals and hard labor were compounded by many documented cases of sexual abuse, blackmailing and outright physical abuse including murder.

Tanzania has laws on the books against all of this. But … few Tanzanian laws of any kind are regularly enforced: Tanzania is a lawless land where social order is sewn together by bribes and sometimes the goodness of local officials.

Tanzania is now the 4th largest gold producer in the world. The $2.1 billion dollars earned annually contributes 3-5% to the entire GDP of the country.

Ninety percent of this is from large-scale, big-machine, high-tech commercial mining. Roughly three-quarters of the commercial mining in Tanzania is controlled by African Barrick Gold (ABG), a UK held multinational; and AngloGold Ashanti, a South African company. The remaining quarter to a third is held by smaller multinationals, the largest of which are the Australian mining company, Resolute Mining Limited, and the German Currie Rose Resources Inc.

Ten percent, though, comes from this off-the-books, theoretically illegal artisanal mining involving the children.

The artisanal mining is usually pursued on the periphery of the commercial mining in areas the big machines just haven’t gotten to yet, or in areas that the multinationals have determined isn’t rich enough for their interest.

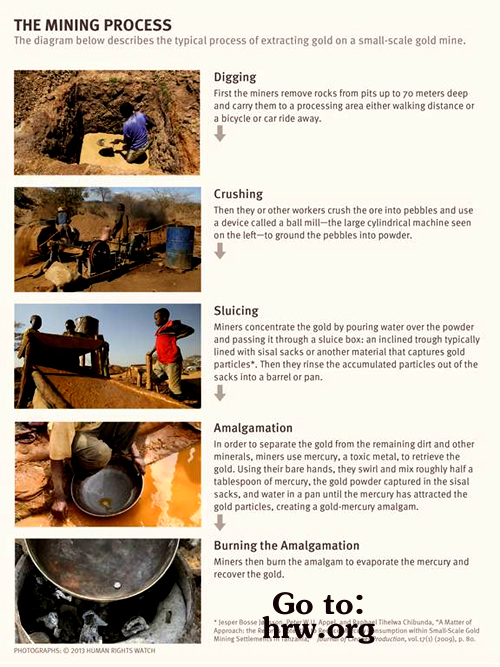

Most of it is surface or near-surface mining, and that’s what lends itself to individual prospectors.

Like mining throughout the ages, there is little guarantee of striking it rich by anybody, but the allure is what keeps the miners going. But in Tanzania, “striking it rich” is phenomenally greater than it is for an Alaskan miner, today; or even those involved in the great western gold rush a century ago.

In Tanzania, a child who finds a gram of gold will be able to sell it, once processed through the toxic mercury process in his pan, for more than $40. In many of the regions in Tanzania where this now occurs, that’s enough to keep a family of five alive, well fed for a month, with some left over for used clothing.

When a child strikes out in the mines, there’s other horrific work. HRW documented children as young as ten earning up to $3 for crushing a pile of rocks, $1.23 for mixing the mercury and gold for another prospector, all of which compounded could earn a kid more than $12/day.

That is roughly what a well groomed doorman, janitor or telephone operator in a safari lodge in Tanzania makes.

The story created here is of a society struggling to be simply clean, healthy and not hungry, putting their lives on the line starting as children, day after day, to reach a goal – a level of existence – in economic terms that is around one one-hundred-thousandth (.001%) of the average earnings ($90,000 annually) of workers for African Barrick Gold living the U.K.

Or one-ten-thousandth (.01%) of the average cost of a gold bracelot. Or should I go down a bit? Do you have any gold earrings? OK. Maybe one-tenth percent of the average cost of your gold earrings? So a thousand chilren work-days in Tanzania equals your gold earrings?

That gap is the problem. Tanzania should be getting a much larger proportion of its gold wealth, and the citizens and children of Tanzanian should be getting a much, much larger proportion of the money its own government earns.

But we know that gap is not getting smaller; it’s getting bigger and bigger as the years drip by. And the children get less and less and sicker and sicker.

Was slavery better?

Jim, it sounds like the big companies dont pay these kids on the periphery? Who does? Or are they free lancers? It was unclear. I certainly agree that more money needs to stay at home, but these are two different issues, no?

From JH: According to HRW the kids are paid either as itinerant workers by the miner who contracts them as a laborer, or by middle-men brokers in nearby towns who are eager to relieve them of their “gram of gold.”