No, do not believe that the elephant population in Tanzania has declined 60% in 5 years. Read the science not the headlines.

No, do not believe that the elephant population in Tanzania has declined 60% in 5 years. Read the science not the headlines.

A couple weeks ago the Paul Allen Foundation and the Frankfurt Zoological Society turned over their elephant census numbers to the Tanzanian government.

The Tanzanian Minister for Natural Resources and Tourism then held a press conference to announced the results:

A total head count of just over 40,000 elephant. Actually I had to add up his numbers which he released piecemeal, but not even clever Tanzanian politicians can alter arithmetic.

The last census, also conducted in part by the Frankfurt Zoological Society, put the country’s 2009 elephant population at around 110,000.

A 60% decline.

Some of the more sexy conservation organizations like NatGeo reacted like a London Daily Mail:

“100,000 elephants killed” NatGeo reported in 72-pica type (or its relative equivalent in my 13″ CRS).

Still believing that some NatGeo products are better than the “Alaskan State Troopers,” a few reputable news media like Britain’s Guardian echoed the “catastrophe.”

The Washington Post cited the press conference as proof of a “catastrophic decline.” (This one really bothers me.)

Moving a tad closer to the truth, some better organizations were more measured:

The Wildlife Conservation Society in its ‘Response to … Elephant Census’ first noted the hefty increase in elephant numbers in the north of the country before three paragraphs down reporting the numbers in Ruaha, which is the component that brought the overall census numbers so low.

The Frankfurt Zoological Society, the lead organization for almost all wildlife conservation in Tanzania, was equally measured in reporting the results.

Like WCS it noted the success with elephant populations in the north before reporting the dire figures but further qualified them by suggesting there was hard evidence from the “carcass ratio” in The Selous that indicated “unnaturally high mortality“ not necessarily related to poaching.

Oooooo….

“Government, Wildlife Experts and Conservationist [are] baffled by the sudden disappearance of more than 12,000 large elephants from Southern Tanzania even though they were neither poached nor died,” reported the Arusha Times.

Oh, my goodness, it’s Babu at work. This is getting spooky isn’t it?

Here’s what’s happening, folks.

These elephant statistic are at long last some of the most reliable numbers ever obtained in elephant counting. I have often written about how confused and contradictory elephant censuses have been.

Many other more credential organizations have, too.

Maybe now, thanks to the Paul Allen Foundation, we’ll start getting it right.

It was Allen’s $900,000 which paid for this census, and it was the most exact, most scientific census of African elephants north of the Zambezi ever done.

But there are 2 major problems with concluding “a catastrophic decline” from the first set of reliable numbers we’ve ever had, beyond the simple common sense that reliable numbers can’t be compared with unreliable ones to make any conclusion:

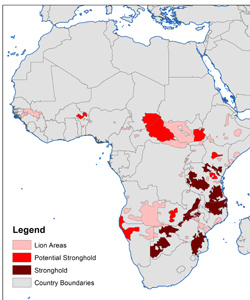

First, this well done census was confined to protected or near-protected wildernesses. There are vast areas of Tanzania, particularly not far from those characterized as having the most “catastrophic” decline, that are not densely populated and perfect habitat for roaming elephants.

Second, the areas of Tanzania that have been very carefully studied pretty well for almost a century, the northern wildernesses, showed an increase in populations in the same study period.

Those northern areas are much more densely populated by people, with all their problems and daily activities and everything else that contributes to human/elephant conflicts. If there is any place where poaching can be documented, it will be in these areas.

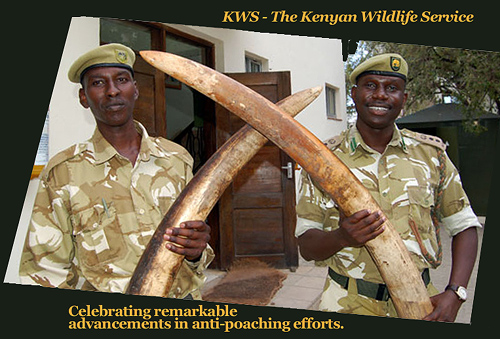

I disagree vehemently with those who claim the human unpopulated vast wildernesses of Ruaha and Rukwa are prime poaching areas because nobody can see you do it. Balderdash. They can’t see you do it in the middle of the Serengeti National Park, either! At least not when you do it with the skill of a real poacher.

These guys aren’t going to waste their resources on the long-distance, sparsely populated, thorntree forests of the vast interior. They may, in fact, be less watched there, but it will be exponentially harder to poach then transport the goods to market from Ruaha than from Tarangire.

So thank you FZS and Paul Allen for at long last starting us on the right track, but those flashy so-called scientific organizations with their hands out … time’s up.

I just can’t wait for the 2019 census!