Canada has just embraced a preservation of native values, whereas Kenya seems forced to aggressively ban them.

Canada has just embraced a preservation of native values, whereas Kenya seems forced to aggressively ban them.

A remarkable investigation published today in Nairobi shows the enormous difficulty that traditional societies have preserving their life ways in the modern world.

Kenyan Anthony Kuria concludes his excellent investigation:

“Children are meant to enjoy the purity of an untainted childhood, have the opportunity to go to school as well as the privilege to freely enjoy and experience the simple things in their lives. Finding alternatives to [“Beading”] is, therefore, an imperative.”

“Beading” by Samburu people in the north of Kenya is a practice closely associated to FGM and forced marriage. Kuria is modern. The people he was interviewing were not.

Samburu land is an area I know well, and I’ll be returning to it in February with another group of loyal travelers. It’s one of the most beautiful areas in the world, very similar to America’s great southwest. And like America’s great southwest, much of it is not particularly hospitable to humans.

Several generations ago the traditional people who lived here – the Samburu, Turkana, Rendile and Boran among others – were strictly shepheds. This is a near universal life way of people all the way from lower Egypt down to the equator who survive in very arid conditions.

The cattle munch what little greenery exists, and there’s not much. So the cattle are forever wizened and probably sick, but they are the critical ingredient for survival of these near-desert people.

The people don’t eat the cattle, they concoct a yoghurt made from the blood and milk of the herd that is probably among the most nutritious health foods on earth! (I have tried it only once and do not expect to duplicate the experience.)

The goats are kept to support the cattle: when a baby cow is born, the mother’s milk is the most nutritious, so it is kept for the people. The calve is taken away from the mother and raised on the less nutritious goat’s milk.

This simple survival method has worked for millennia for millions and millions of people. But in my life time radical changes have beset Africa. The arid lands are now rich with oil and other minerals. Even leapfrogging fossil fuels, many remote parts of the near deserts of Africa now support massive solar and wind farms.

This rapid change dislocates traditional peoples and their values. “Beading” was part of a lengthy process of ritual in the traditional Samburu tribe, linked to FGM and forced marriage, that probably was as critical to the survival of the Samburu as were cattle.

But it’s not just that it has changed, it must change.

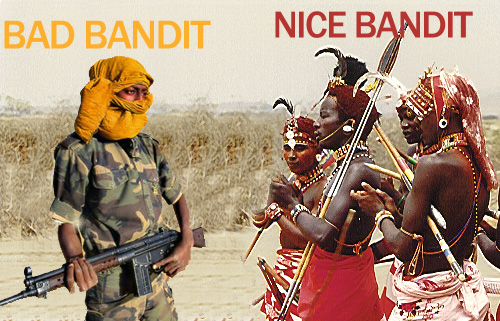

In today’s modern Africa those who linger in the past are tread upon, ignored or miserably manipulated. They become the pawns in terrible conflicts, as today we see in Samburu where ancient enmities between various tribes are exaggerated by modern weaponry and instant communications.

Modern police often find themselves in the crossfires.

FGM and associated practices like “Beading” have been outlawed in many African countries for a number of years, but enforcing these laws has – until now – been intentionally lax:

“Jail sentences only last a few days or weeks after which they are released on condition that they will not violate the rights of the girls again,” Kuria reports.

The main reason enforcing “modernity” is so hard in places like Kenya is because in the modern world, not the traditional world, tribal practices are deemed wrong and immoral. That’s a near unbridgeable divide.

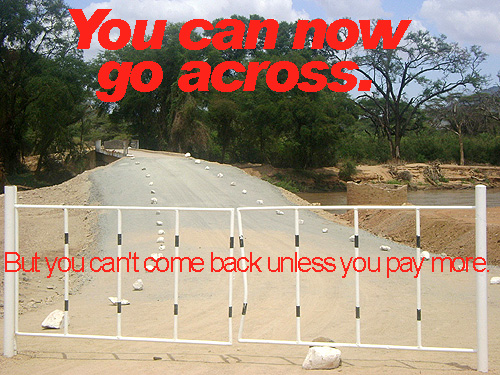

Were development to occur more rapidly: were more good schools built more quickly, more good roads laid, more electricity provided, then the preeminence of “modern” becomes inviolable. But that isn’t the case yet in much of Samburu.

Not until deep oil wells or huge solar farms are cut into the landscape does real development come along. That brings its own controversies among modern Kenyans, just as among modern Americans.

“Beading,” FGM and forced marriage ought not be condoned. But to ban them without providing modern alternatives to the people who still embrace them is as equally wrong as to allow them in our more enlightened world.