A Congolese ballet currently moving through Europe’s summer festivals strikes a remarkable difference between American and European compassion to Africa. Maybe compassion per se.

A Congolese ballet currently moving through Europe’s summer festivals strikes a remarkable difference between American and European compassion to Africa. Maybe compassion per se.

Congolese choreographer Faustin Linyekula is currently restaging a near century’s old ballet called “The Creation of the World” that was first produced in France between the world wars. At that time it was widely called “The First Negro Ballet” since its depiction of emerging humankind was black, and as such, included pioneering black performers at a time when blacks worldwide were pretty much confined to trumpets and drums.

It became impossible then, and remains impossible now, to view this ballet as anything more than white people’s fantasies about black people’s existence. Racism in its most theoretical forms.

The ballet’s storyline is basically biblical, but the world that emerges is not flowering with white lovers under a perfectly formed apple tree. Instead, mankind births into something rather depressingly horrible: skin without bodies, torsos without hearts, and babies in abject suffering. Essentially, mankind without a soul.

And in the Bible’s remarkable way of accepting suffering as simple destiny, it prevents the viewer from leaping to any remedy. There is no hope things will get better in the ballet. The story ends in misery.

Linyekula’s thundering question is “How could they not see the suffering?” The English translation was made by Radio Netherlands after Wednesday’s performance in Amsterdam, and it’s right on.

More exactly Linyekula means why did they not react to the misery during the colonial age, and now, why are non-Africans not assisting Africa more than they are?

The question begs the question about compassion. And it’s logical that those who are responding most compassionately (Europeans) will also be challenged more often (than Americans who are doing less) that they are still not doing enough. That’s what Linyekula is trying to do: tug on the European’s guilt, egg them on to even greater compassion.

“The Creation of the World” wouldn’t succeed in America, today. Like anything troubling, there is a threshold of assumed responsibility, and I believe Europeans have a greater tolerance for heavy lifting in Africa than Americans. A greater compassion.

It would take me a book to dissect the cultural facts of current European antipathy to immigration vis-a-vis its greater compassion to mankind as a whole than American’s. But I do believe that:

Americans are fast losing their compassion, compassion for almost anything but themselves. Whether Europeans in contrast are growing more compassionate and tolerant is hard to measure on its own, but in contrast to America they most certainly are, despite the wave of anti-immigration sentiment polluting Europe, today.

The ready measures of this regarding Africa specifically are foreign aid and private investment, government engagement (military or otherwise) and free trade agreements. In all these areas, Europe is racing past America despite Obama’s attempts to stay even.

Europe is in a much worse economic situation than America. Why, then, is Europe reaching out to Africa more than America? The first reason is because of America’s current obstructionist Congress. But there are deeper reasons as well.

Europe is closer to Africa than America, so trade and investment is easier. It has more immigrants from Africa and it has a more pressing problem of refugees from Africa than America. But there’s an even more important reason in my view: there’s more guilt.

Few societies in the world used and profited from slavery as much as America, and we all know where they came from. But that’s perhaps too long ago for any residual guilt to move us in any contemporary fashion to greater compassion. The colonial period in Africa which emerged as slavery was being ended was dominated by European powers and lasted for a very long time. It’s not “so old.”

That was a mostly wretched period in world history. Parliaments in Portugal, Belgium and France have all apologized and paid reparations for their society’s unjust colonial involvements. The Catholic notion of repairing past wrongs by dropping a penny in the church’s collection box is a very European notion.

(And, by the way, it often works and has a much greater impact than lovely speeches about morality and compassion.)

To be fair, though, the production is not being swallowed whole in Europe. Linyekula actually extended the ending of the original production exaggerating the “misery.”

A respected French arts critic, Marie-Valentine Chaudon, asks “Does Linyekula go too far” implying European disinterest with the African suffering she accepts was in large part caused by the colonial period.

Perhaps. But what saddens me is that “maybe too far” in the European mind is outright “extra-terrestrial” in America’s, today. And while I’m no dance critic, I think the art Linyekula clearly has turned for political and social purpose is extremely valuable.

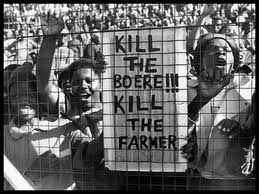

And I sorely wish we in America could achieve the same level of self-inspection with regards to racism, with regards to our lack of compassion.

Flip it, white man. What if you were, well you know, the other… color. They sang in London, but they were from Africa.

Flip it, white man. What if you were, well you know, the other… color. They sang in London, but they were from Africa.