Jim is on vacation until he guides his last safari of the year beginning on July 24. Here are some of his favorite pictures taken on safari with him in Africa. The above shows an Egyptian Mongoose standing down some juvenille lions in Kenya’s Maasai Mara.

Jim is on vacation until he guides his last safari of the year beginning on July 24. Here are some of his favorite pictures taken on safari with him in Africa. The above shows an Egyptian Mongoose standing down some juvenille lions in Kenya’s Maasai Mara.

Category: Mara

OnSafari: The Mara

Why spend the time and money to travel north on a Tanzanian safari to the very border of Kenya, and then not cross?

Why spend the time and money to travel north on a Tanzanian safari to the very border of Kenya, and then not cross?

I ended my extremely successful McGrath Family Safari game driving along the great Mara and Sand Rivers, seeing really giant crocs, looking longingly to Kenya. You aren’t allowed to cross over.

Ever since the 1979 dispute between the two countries closed the border, numerous attempts by good politicians on both sides have tried to reopen it to no avail.

Oprah stood where my family had lunch yesterday, peeved to smithereens that she wasn’t allowed to cross a few years ago.

Nobody can. Not even the politicians themselves.

The dispute is now so old that recounting its history is like critiquing a marble statue: Interesting, but it’s not going to change.

We had great game viewing these last two days, including a family of 12 lion in a weeded kopjes, elephant playing along the river, giraffe starting at us as we bumped and hurdled ourselves over really bad roads, and to everyone’s glee, 5 baby rock hyrax popping out of a rock design placed at the edge of our camp’s swimming pool.

But it’s a long … and expensive journey to get here. Obviously we aren’t unusual, because the camp we stayed in, Asilia’s Sayari, is expanding (now 15 tents) and is one of the most expensive and luxurious camps in Tanzania.

The southern (Tanzanian) side of the rivers that make up some of the border with Kenya are filled with camps. We encountered almost as many game viewing vehicles as we did in Tarangire. So clearly, we’re not alone.

The attraction is the allure of the migration. Read my last blog to see how crazy this is! Yet we are all driven by history, and in fact the chances today of seeing the great herds in Tanzania are definitely chances that on every day of the calendar are moving northwards.

But more correctly – and this is my own experience – they aren’t moving as much. It’s wetter, so more grass, and areas previously dust bowls at certain times of the year in Tanzania are no longer.

Personally, I love the Mara. In Kenya it’s called the Maasai Mara. Here it’s called the Mara District. But it’s the Mara, absolutely one of the most beautiful places on earth.

It’s cold at night like Seronera, but it never gets really hot during the day even with clear skies. It rains almost every day of the year except in October and November, which I love because it’s not the least disruptive (it never rains for long) and it’s dramatic and turns the veld into a bouquet.

(P.S. The animals like it, too.)

There are woodlands, but they aren’t as dense as further south, so you can reach a rise in a hill and have vistas that stretch for dozens if not hundreds of miles. It’s a lush carpet of greens: the shining reflective green of grasses and the deep dark fur greens of the trees and few woodlands.

And, of course, the rivers. We spent most of our time up here along the Mara River. It’s a raging, but not very deep river, bubbling over lots of big rocks producing white water and little cascading waterfalls everywhere you look.

Also everywhere you look are hippos, uncountable there are so many, and some of the world’s largest crocodiles. I think the biggest one we saw was probably 14 feet, but I have seen them twice that size!

The birdlife is exceptional. First of all, things are easier to see when the woodlands are thinned out. So, for example, we saw numerous klipspringer, steinbok and reedbuck, and even an oribi! These aren’t rare animals, just difficult to find because of their size, color and stealth.

The same is true for birds. So within a half hour we saw a hoopoe, a pygmy falcon and the pink-eyelidded Verreaux’s Eagle Owl!

But it’s not all good news. Tanzania – at least up here – pays a lot less attention to its wildernesses than Kenya. So there are many, many more tse-tse. There are many fewer tracks that we can use. And most of all …

… Tanzania does not allow off-road driving as the Kenyans do in the Mara. That’s critical. The official Tanzanian position is that it damages the ecosystem, and there is some truth to that.

But it’s a little truth, and the real truth has to do with Tanzanian corruption and lack of resources dedicated to tourist parks. So as Kenya calms down (the British removed their travel warnings on the Kenyan coast last week) I think that I and most of my colleagues will choose to travel to Kenya to see the Mara rather than here.

But the McGraths and all the others we met here this time made absolutely the right decision. The southern Serengeti remains my favorite place, but … the Mara is a close second!

Dangerous Plays

As access to Africa’s wildernesses develops and improves, visitors are becoming less respectful and careful. This puts everything in jeopardy.

As access to Africa’s wildernesses develops and improves, visitors are becoming less respectful and careful. This puts everything in jeopardy.

The photo above of a self-drive tourist in Kenya’s Maasai Mara game reserve last Sunday “posing” in front of a pair of lions was taken by a film crew at some distance from the tourist. Presumably the tourist didn’t notice the film crew.

The series of photos was first published in London’s Daily Mail. Click here for the full sequence.

The tourist spots the lions, which seem to be about 15-20 meters away. He stops the car then exits the passenger’s side (right side) which is the opposite side to the lions.

He then races around the car to place himself between the car and the lions, leans back with a thumb’s up obviously posing for another person in the car who probably takes a picture. He then runs back around the car and gets back in.

The photos capture no reaction from the lions other than an occasional glance at the tourist.

These are certainly wild lions, and why they didn’t react is impossible to say. They appear to be a mating pair as it is unlikely to see only one male and one female alone together.

Lion mating is pretty routine: It lasts about three days during which time the pair often can’t be roused by anything, not even hunger. But not always, and it’s impossible when first encountering them to determine at what stage in the three-day mating process they are.

I’ve encountered a mating pair when the male charged our vehicle. There is often a vicious fight between males for the right to mate prior to the mating commencing, so it was possible we arrived just as that altercation had ended.

I’ve also seen mating lion break apart to join a kill. Once again such an anecdotal encounter could be nothing more than having happened to arrive just at the end of the mating process.

I don’t think it’s possible to conclude why these lions were so passive in this case. I suppose an equally cogent argument to my own anecdotal experience is the clear fact that more and more tourists are seen by lions, now. Generations of lions in places like Kenya’s Maasai Mara are becoming more used to people and learn that they aren’t threatening.

That, of course, is a degradation of the wilderness but one that I can hardly oppose. Without tourists — at least in Kenya — there would be little wilderness left.

We are at an interesting crossroads in the development of African wilderness for tourism. As so clearly illustrated in this example, wilderness is taking on the characteristics of a theme park, one that definitely has elements of danger in the experience which seem precisely to be one of the main attractions.

And at least in this case flirting with that danger is apparently one of the selling points.

There are dozens of stories of tourists going too far and paying the price. Just google “tourist killed by lion” or “tourist killed by buffalo” for a tidy wrap-up.

Many of these tragedies aren’t quite as wanton stupidity as evidenced in the photo above, but many are.

What concerns me most is that as more and more of these incidents occur, lions and other wildlife will grow more and more accustomed to man and his peculiarities. This seriously jeopardizes their own wild behavior.

There are many people in Africa who consider lion in the same regards as Montana ranchers consider wolf. A tamer lion is much easier to kill.

And there will be more and more tourists injuries and deaths as well. These two ends of the stick will burn right through to the middle, and tourist parks like Kenya’s Maasai Mara will either have to become far more restrictive or will simply be sold to wheat farmers, or both.

The result is that there will be less wilderness for us all to enjoy.

On Safari: Migration Drama

The Kisiel family’s last two days on safari featured the great migration at its best, including a croc feast of a wildebeest river crossing.

The Kisiel family’s last two days on safari featured the great migration at its best, including a croc feast of a wildebeest river crossing.

We expected to find the migration in the north, and we did. We flew from the central Serengeti into the far northern Serengeti landing virtually in sight of the Kenyan border. Although our lovely Kuria Hills tented lodge was a half hour south of here, we spent most of the time game viewing in the north.

Five minutes after we left the airstrip in the Mara Region of northern Tanzania we were skirting the south and west banks of the great Mara river. Crocs so big I call them “dinosaur crocs” were everywhere, waiting for one of the two meals they eat each year.

We saw one monster that John Kohnstamm said was 24 feet long. Close. But on that first day, no wildebeest near the river that we could find. So we headed south to camp through absolutely beautiful Mara grasslands and rolling hills.

That afternoon we saw our first oribi, not something many safaris see. It’s a gorgeous little, somewhat hyper antelope with large black face spots.

We also saw a number of wonderful birds in addition to the common headliners like the lilac breasted roller. Add the gorgeous cliff chat, rosy-breasted lark, perhaps a hundred red-cheeked cordon bleu among many others.

The next morning – the Kisiel Family’s last morning – we packed a picnic lunch and left before dawn.

We stopped on a ridge that looked north into Kenya and waited for the African sunrise. We had flushed out many square-tailed nightjars having listened to their woeful scream in the night. Then about ten minutes before dawn the omnipresent ring-necked dove began to fill the veld from horizon to horizon with its hypnotic song.

And then a few minutes before sunrise the whole veld exploded with bird song, and Africa’s giant sun peaked up blaring a perfect red-orange orb through the thick morning haze.

We traveled all the way past the southern Sand River border of Kenya and began searching along the Sand River. There we saw what will always be one of my most precious safari events.

We were driving somewhat hidden in the heavy bush at the top of the 15-foot embankment of the Sand River, which unlike the Mara, usually has an all sand bottom with good and copious amounts of water flowing under the sand.

But there has been so much rain that there were actual streams in the sand river bottom.

We came upon a lion pride eating a recently killed wildebeest. There were two lionesses with seven cubs in two different litters, plus a young and magnificent pridemaster, plus a slightly younger juvenile male that already was bigger than Mom and was sprouting a wonderful new mane.

What was specially interesting was the fighting that we watched between Mom and this juvenile male. She would not let him eat.

He could easily have whooped her, since he was bigger and stronger, but her motherly instincts knew it was time for him to be kicked out of the pride. Not too long before we had seen two other males about his age, sulking on an anthill starving as a ring of wildebeest surrounded them.

Young males don’t know how to hunt. They have to teach themselves, and if they don’t, they starve. It’s the reason there are more females in the overall lion population than males.

So the juvenile male that had somehow managed to stay with the pride was trying a new tact. But it wasn’t working.

Any move he’d make, even the slowest and most methodical attempt to raise his leg on the embankment to scoot away, and Mom would snarl and attack him. Finally, he slipped away.

We had seen in about twenty minutes what wildlife photographers take years to document.

But believe it or not, the best was yet to come.

Thinking we’d seen it all, sated with experiences, we began to head home along the river. Lo and behold there was a small group of wildebeest and zebra that looked like they were ready to cross the great Mara River.

And below them, to the right and left and side and bottom, were giant crocs waiting. They were steady in the water despite the strong current, or on the embankment, or on the island rocks, just waiting … waiting.

So… we did, too.

Roy Stockwell kept saying to the wilde across the river, “Come ‘on guys, the grass is much sweeter on this side!”

Whether it was Roy or not, they finally came, in a sudden leap from the bank followed by leaps across the great river.

The crocs moved in from every side. One dinosaur sailed straight for a calve and pulled it under and another on the other side took down a yearling.

Both started screaming and the mother of the calve turned around and jumped back in the river, literally pouncing on top of the croc, but it was no use. He took it under and she leaped exhausted back onto the shore.

The larger yearling drew many big crocs as they started vying among themselves for the feast.

Camden Reiss, like many many kids and adults as well, didn’t like what he saw. And it is a terrible moment, and yet when we as the real king of the beasts step back to let nature do her thing, we realize there are as many wonders as catastrophes.

“Can’t get better than this!” Grandpa shouted.

Cheetah on Car!

Cheetah jumping on cars went YouTube viral this holiday season, and traditional criticisms from wildlife managers was starkly absent. Is this OK?

Cheetah jumping on cars went YouTube viral this holiday season, and traditional criticisms from wildlife managers was starkly absent. Is this OK?

The newest video had nearly a quarter million hits this morning but it is hardly the only one. I stopped counting at 20 separate YouTubes of cheetah on cars, and there are countless stills on Flickr and even more individual photos on private blogs.

My own experience includes at least a dozen such incidents. Most of them were in Kenya’s Maasai Mara, but some of the most memorable incidents were in Tanzania’s Serengeti. The striking difference as relates tourism of the two areas – the Mara is generally very crowded and the Serengeti generally absent of crowds – has led me to believe that there is something hardwired in the cheetah’s brain that gives it a potential pet syndrome.

Hard-wired may be too strong, and I can understand how generations and generations of cheetah being unmolested by people could nurture up the same behavior, but either way, the cheetah is clearly the closest thing to a pet you’ll encounter on a big game safari.

Not every cheetah displays this friendly behavior. I’ve encountered many which are extremely skittish, although none of these frightened little beasts were in the Mara – they were all in the Serengeti or more distant places like Kenya’s northern frontier. The best I can remember virtually every cheetah in the Mara looked friendly.

Why do some, then, but not all jump on the cars?

It’s a pretty simple answer. A hungry cheetah begins its hunt in an incredibly laid-back fashion. The eyesight of the cat is so powerful that it can scan the plains with almost the same facility as a falcon surveying the turf below.

The best view is the higher one.

And like falcons and other raptors, prey is often discovered but then doesn’t always trigger an attack response. I suspect this is often because it’s just too far away, but there’s probably dozens of other reasons as well.

Perhaps the cat’s level of hunger just hasn’t reached the threshold of action, or perhaps the cat also sees competitors in the area and the cheetah is the smallest of the big cats, easily chased off its prey by a host of other animals like hyaena.

In any case, the cat on your car roof seems incredibly relaxed, hardly hunting. But that’s exactly what it’s doing. Fat cats – non hungry cheetahs – will never be found atop a car.

There is one exception. Youngsters learning to hunt will often play on the car, hungry or not.

There is one exception. Youngsters learning to hunt will often play on the car, hungry or not.

Not too many years ago, researchers and rangers were highly critical of these tourist interactions. Pamphlets were placed strategically on lodge reception counters and I even remember a series of “ranger talks” warning guests not to approach cheetah too closely.

The argument was that the cheetah was easily distracted by tourists, and would therefore often have its hunt disrupted. I found that specious.

But there are definitely reasons to avoid too close an interaction. Cheetah is the only cat whose claws don’t retract, so it has no power to decide whether to inflict a wound or just give you a love swipe if you accidentally surprise it.

I learned this when Kumati, an old cheetah that lived by Naabi Hill, jumped on my car as we were headed to the airstrip for a flight. No matter what we did, we couldn’t get him off. Finally I stepped out of the car and swiped him with my hat, which he ripped back in turn!

I learned this when Kumati, an old cheetah that lived by Naabi Hill, jumped on my car as we were headed to the airstrip for a flight. No matter what we did, we couldn’t get him off. Finally I stepped out of the car and swiped him with my hat, which he ripped back in turn!

Of my many memories of cheetah-on-car the funniest one was with two football players from a prominent American college traveling with their much smaller mother. We stopped in the middle of the Serengeti – virtually all alone for miles and miles – to watch a young family strolling along the plains.

Several of the youngsters jumped on the spare tire on the back of the vehicle. The right guard shoved his mother towards the front of the inside of the car, then ripped out one of my seats and pushed it towards the cheetah shouting, “Down Mother!”

A big male cheetah might reach 90 pounds. Most females are around 60 pounds, and this means they are generally about the same size as your lapdog.

Is there any real harm with all this?

I don’t think so. As I learned with Kumati, don’t try to pet them! But conceding a better view and just enjoying the experience strikes me as mutually beneficial!

Another Black Day in Kenya

Visitors and citizens alike were horribly killed in Kenya yesterday reflecting a very strained society.

Visitors and citizens alike were horribly killed in Kenya yesterday reflecting a very strained society.

As of this morning four tourists are reported dead with several others still in critical condition after a scheduled flight aboard of Mombasa Air Safari LET aircraft from the Maasai Mara to Mombasa crashed on take-off.

Forty-eight Kenyans were killed in ethnic clashes near the town of Mandera in the arid Tana River region far east of Nairobi.

The two quite different incidents both reflect Kenya’s growing strain as it prepares for critical elections next March.

The Mombasa Air Safari crash was of a Czechoslovakian made, Soviet-styled LET aircraft. LET aircraft (of a variety of different sizes and types) has a horrible safety record with twelve accidents and 424 fatalities just this year alone. It was a cheap aircraft to begin with that became even cheaper with the breakdown of the Soviet Union. Almost like bad weaponry, LET aircraft have been showing up more and more in Africa as lax aircraft regulation mixes with strained economies.

The ethnic clashes which have been mostly reported in the world press as revenge killings by one ethnic group against another for disputes over water resources and range rights is actually only the tip of the story.

Kenya has redistricted itself in preparation for next year’s elections under the new constitution. Multiple smaller districts have been consolidated – as I believe they should – to create a truly more representative parliament.

And one logical outcome pits former established politicians as competitors for a single representative seat. It isn’t just coincidence that this is the case where the ethnic clashes occurred yesterday.

Police have confirmed that villagers have been incited to violence by local politicians vying for a consolidated district under the new constitution.

To a certain extent both these tragedies are isolated. Kenya tourism – indeed more and more of East African tourism as a whole and almost all of southern African tourism – depends upon small aircraft. I’d estimate in East Africa that more than half the tourists take at least one such flight, and likely a quarter take two or more.

The overall safety record for such a massive industry is pretty good. LET aircraft represent a very small proportion of the tourist aircraft, which are predominantly very safe Cessnas. (Unfortunately, there are no actual statistics, although the data is there to compile. So my statements are not evidential, but I believe accurate enough.)

And the ethnic clashes in Mandera which have been picked up in the world press as evidence of Kenya’s overall ethnic strife is nonsense. The new constitution, some pretty harsh laws, four prominent citizens on trial in The Hague for causing ethnic violence in 2007 all point to a Kenyan society righting itself masterfully.

But dead is dead. Another few hurdles for this tough and struggling society.

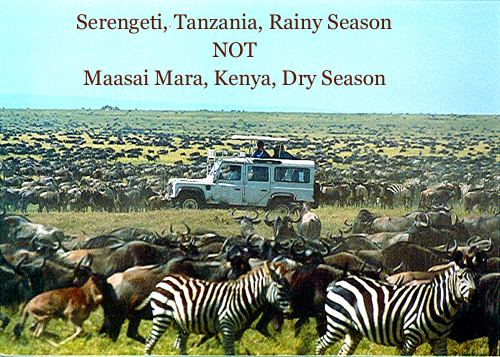

Hot Migration Topic

Is it really such a burning issue: why are the wildebeest so late?

Is it really such a burning issue: why are the wildebeest so late?

I’ve often experienced them crossing from Tanzania to Kenya even later, sometimes not until August. Normally, though, the herds cross the two river border that separates Tanzania from Kenya by mid- to late June, so we’re a month behind.

This year it’s stinging Kenya more than before.

Kenya’s tourism is reeling from terrorism and a rapidly inflating currency. So the few tourists coming to the Mara who are expressing disappointment is just another blow the Kenyans don’t need.

Looking anywhere for a reason their vacation has been diminished, there are a number of American tourists now blogging incorrectly that the reason the migration is late is because the Tanzanians are setting fires in the Serengeti which is disrupting the wildebeest from moving north.

And of course the general collection of end-of-the-world nuts have picked up this version of what’s happening.

They’re all wrong, but first let me explain where the less apocalyptic are coming from.

The wildebeest eat grass and nothing but grass. Their traditional migration patterns are based on where the grass grows when. It’s that simple. Historically the rain pattern traces a parabolic circle the north of which is Kenya’s Maasai Mara and the south of which is Tanzania’s Serengeti.

For more detail, click here.

The rainiest place in East Africa is Kenya’s Maasai Mara. When it’s dry everywhere else, it rains in the Mara, so the wildebeest go there. The Mara is higher and more rocky and has more acidic soil than in the Serengeti, and so the grass isn’t as nutritious. But at least it grows when it doesn’t grow in the Serengeti.

Separate from this rain dynamic that guides the migration is the age-old agricultural and wildlife management question about whether or not to burn grasses on a prairie.

A proponent of burning that I trust explains the necessity as the only way from keeping the prairie from turning into a forest. Most scientists agree with this explanation, but they also disagree that’s good. Most science suggests burning isn’t overall a good strategy for either agriculture (slash-and-burn) or wildlife management. In other words, it might be better to have a few more forests and a few less prairies.

The argument has been going on since Caesar.

Here’s a blogger that’s got it right.

Whichever side you choose, the fact all agree on is that the increased prairies in East Africa over the last half century is part of the reason that the wildebeest population has tripled. Another argument is over whether the current huge size of the wildebeest population is good or not, but certainly from a tourist point of view it is.

Both Kenya and Tanzania park rangers burn their grasslands. Come September and October when the rains return to parts of the Serengeti and the herds begin to leave Kenya, Kenyan rangers start furiously burning to delay their departure from there.

So both sides do it, and both sides argue they do it for scientific reasons, albeit there is a short-term benefit that does for a very short while delay the herds. Burning, as you may startle yourself from remembering 3rd grade science, produces water (moisture) which drops on the burned prairie and immediately sprouts new short grass even without rain.

Alas, a very tempting reason to stay and have another bite.

It was very unfortunate that an excellent Kenyan newspaper, Nairobi’s biggest, propagated the inaccurate story. It’s beneath the standard of the Daily Nation but even worse, suggesting the fires are being uniquely set as a blockage rather than just the normal half-century old grass burning strategy is totally irresponsible.

The greatest reason the herds are late is because the rains – like everywhere in the world – have been very unusual. I’m sitting in a place of a horrible drought. East Africa – northern Tanzania in particular – has had unusually heavy rains, and this has resulted in much more new late grass.

The migration isn’t so hard-wired that animals will leave a food source. Migrations worldwide are driven by food sources. We had an unusual warbler migration this year in the Midwest, because bugs – their food – appeared earlier than normal.

Burning is incidental to this, perhaps a short-term fix delay (a week, maybe two) but nothing more significant. Tourists who believe they can fine tune their “migration vacation” in periods of two-weeks are nuts.

Tanzanians blame Kenyans for everything wrong in Kenya, and Kenyans blame Tanzanians for everything wrong in Kenya. In this case there’s nothing wrong to begin with.

Except bad reporting and tourists who didn’t do their homework.

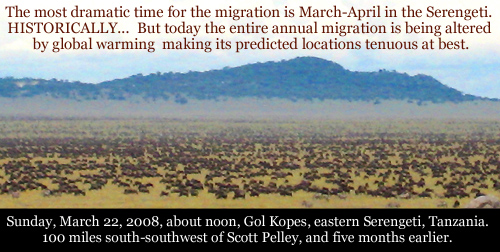

Way South of Scott Pelley

Sixty Minutes rebroadcast of “Into the Wild” Sunday night caused many of us experts serious angst. Basically three wonderfully short thumbnails of things wild in East Africa were riveted with inaccuracy.

Sixty Minutes rebroadcast of “Into the Wild” Sunday night caused many of us experts serious angst. Basically three wonderfully short thumbnails of things wild in East Africa were riveted with inaccuracy.

I’m sure that when a professor of dentistry speeds past a billboard for toothpaste he winces. Nothing wrong really with telling people they need to brush. Nothing wrong really with fluoride in the goop. Nothing wrong with a beautiful woman smiling like a bleached Mayan temple.

But probably lots wrong with everything in between, like how often, how hard, when and with what kind and temperature of water, and who knows what else.

I hope the bristles on my back as I watched the 60 Minutes show weren’t as stiff as a Number 10 toothbrush. (Admission: I watched the tape. I had calculated that the Patriots/49ers game would be less stressful. Wrong.)

There were three segments, and the most egregious was the best and first, about the great migration, the Mau Forest controversy and how it effects the Mara River, and the transformation of some Maasai land into community based tourism projects.

Most egregious because it was very, very close to the situation as I see it, but agonizingly not spot on, providing opportunities for enormous misunderstandings.

Pelley and crew were in Kenya’s Maasai Mara, which represents approximately 5% of the land area of the Serengeti/Mara/Ngorongoro ecosystem through which the migration moves. He was correct in pointing out that the migration was there “for a very short time every year” but arrogant and irresponsible in claiming this is its most dramatic moment.

Some years, yes. Most years, no. The drama moves with the weather, and the simple historical odds will place the greatest drama of river crossings at the Grumeti or Balanganjwe rivers in Tanzania, not the Mara in Kenya as Pelley claims.

Pelley said that the “few days that it takes the herds to cross the river, crocs will bring down enough food for months” implying that the river crossing in the Mara is brief and singular moment for any given group of wildebeest.

Not true. Wildebeest cross rivers back and forth multiple times for no good reason. It’s an instinctive part of their overriding component “to follow.” They might have crossed the river ten minutes ago, and another group is crossing in the other direction, and off they go. A single wildebeest might cross back-and-forth a hundred times the same river in the same year.

The problem here is that Pelley is treating the migration like so many casual observers as the sum of its parts, individual wildes on some monarch butterfly calculus of pretty constant direction. That’s just not the case with the migration.

From year to year the actual movements of the migration change massively. There are even years when it never gets to Kenya, or hardly at all. Unlike butterfly migrations, the wilde aren’t hard-wired with a map. They go where there’s grass. And grass grows where it rains. And over time there are definite patterns to this, and which right now are being dramatically altered by global warming.

I have other serious concerns, but none as important as the above: Pelley’s claim that the migration is predictable and that its “most dramatic moment” is in “late summer” when the herds cross “in a few days” the Mara River in Kenya’s Maasai Mara. Wrong, wrong, and wrong.

Kudus though, and not of the animal kind, to Pelley for a thoughtful thumbnail of the Mau Forest controversy and of some local Maasai attempts to transform a dwindling agricultural lifestyle into tourism.

Finally, a recurrent criticism I have of American media is their lack of due diligence. The show used three experts for its three different segments. Two of the experts are honorable scientists to be sure, but none of the experts are current leaders in their fields.

Most of the current leaders of field research are no longer found in Kenya, or at their foundations in the United States. They are brilliant, younger and performing exceptional scientific work, many more in neighboring Tanzania than Kenya. It pains me constantly how a lack of effort by American media leads them not to the true sages but to the hack celebrities.

Nuff said. In sum it wasn’t bad. But to be good it needed care that perhaps no American TV is capable of. BBC where are you?

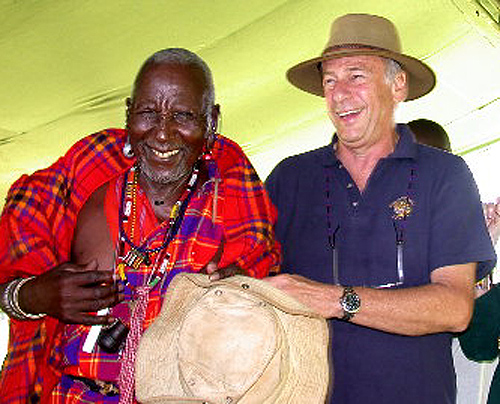

Heri kufa macho kuliko kufa moyo

Great circus barkers are so accomplished that they spur the tiger through the blazing ring so effortlessly it creates joy from daring. That was Ari Grammaticus.

Great circus barkers are so accomplished that they spur the tiger through the blazing ring so effortlessly it creates joy from daring. That was Ari Grammaticus.

In this case, the cheetah on the roofhatch. Ari Grammaticus died last month. His memorial service is tomorrow in Nairobi. With him goes the personal daredevil thrill that was the keystone to many early safaris to Africa.

Ari was the son of a Greek railroader who found himself in Kenya in the spring of safari travel. Film had become cheap and powerful. Air fares were cheap and numerous and Americans in particular began to travel like they never had before. And the British colony of Kenya was newly independent, reshuffling the deck of privilege and business opportunities in ways few could have imagined.

Often you never know if some successful person had a good time or not. Ari had a good time. His smile was infectious. He wasn’t a front guard but he was a big man for his time, and certainly matched any Maasai that he encountered. For some reason that became his connection, Maasailand.

Repeatedly and regularly, Ari traveled to Maasailand until he secured management of a piece of Maasailand that I doubt anyone at the time could truly value. It was on the Mara River about 20 miles north of the Tanzanian border and about 25 miles northwest from at the time the only road into this new non-hunting game reserve called the Maasai Mara.

That was in the early 70s, a year or so before my own first safari. The first place my wife, sister and brother-in-law camped was in this reserve off that main road near a place that remains the focal point for the Mara, Keekorok.

Today the Mara is Kenya’s most important game reserve, whether you measure animal viewing, game management, ease of flying in and out of (there are more than 15 flights daily from Nairobi), range of accommodations or tourist revenue streams.

But not then. The only reason we stopped there was because it was on our journey into the great Serengeti, which we did the next day at first light. The Serengeti and Mara share the political border between Kenya and Tanzania. Then, as now, you can’t really tell where one country ends and the other begins.

But today and since 1979, tourists can no longer cross that border. Until 1979, the Mara was hardly anything but a way station to get to the Serengeti. Today it’s the end of the line for Kenyan tourists, and what a fine end it is!

Ari created Governors’ Camp. (Plural today; very singular back then!) To begin with it was a brilliant name, encapsulating the colonial era with abandon. (Today it would be politically incorrect. Today’s camps all carry local names for area clans or African animal names or local geographical features like rivers and hills.)

But what Ari did was build a tourist camp that recreated the admittedly bold comforts that colonials eked out of the surrounding poverty. There was no need for an apology, then, it was the way things were. Africa was being developed, and if you wanted visitors to come see, they needed a toilet. Animals second.

And so they came. His first camp was Governors’ Camp, today referred to as Main Camp. I remember the old days at this camp before the border closed. It was luxurious by anyone’s presumption of what camping would be in those days: actual toilets (although not exactly quick flushers), hot-bucket showers, and a bed on a frame!

One of the greatest treats I as a young guide had in those days was scaring people to death about camping in Africa! Intentionally, we told them very little, or told them about our own personal camping adventures which certainly no travel insurance would have dared cover. And when they got to the camp and saw the privacy and comfort, we had customers for life!

Governors’ modernized with the times, of course, but it never went over the top, like so many did. Even today there are still pressurized gas lamps as your tent’s main source of light. The beautifully wood paneled bathroom is completely functional with modern plumbing all around and amenities of soap and shower gel and all that stuff.

And Ari modernized, too. He built several more camps nearby, including the more contemporary and luxurious Il Moran. He assumed management of a beautiful lake manor house about half way back to Nairobi, and he built a retreat on Lake Victoria.

And his last great achievement was partnering with a several local organizations and the African Wildlife Foundation to build and manage Sabyinyo Lodge in Rwanda for mountain gorilla viewing. There is absolutely no question that this is the finest property anywhere in gorilla land.

We non-Greeks have this pervading notion that Greeks are first and foremost family men. Ari’s sons now take over for him, and his grandchildren were by his side when he died. Once his friend or his customer or his employee, plan on a lifetime.

Time and again he employed one of the finest camp builders in Africa, even though time and again the builder fell off the wagon while building the roof. I was a certain critic of some of his aging driver/guides, particularly when they starting losing their sight, and of some of his cooks who I felt boiled food too long, but Ari was steadfast. Many claimed he was pinned down by the peculiar and nepotistic politics of Kenya, and that may be. But it all fit a better image:

Heri kufa macho kuliko kufa moyo.

The Swahili proverb is one of loyalty and constancy. What you see isn’t as important as what you feel. The first time I arrived the little tree barrier into Governor’s Camp, some smiling guard saluted me like I was the King of England. Since then there have been hundreds of thousands of guests that followed me. And yet today, you’ll be saluted.

But times have changed. What Ari did can’t be redone. The world has modernized too much. Travelers no longer go anywhere without insurance, cell phones and extra medication. You can’t fool them anymore with a flush toilet.

Unless, of course, granddaughter Amy decides to develop Taurus-Littrow.

To Kill or Not To Ele

Have you ever heard about that little kitty that was taken far, far away and dropped in a forest but found its way back home? What about an elephant?

Have you ever heard about that little kitty that was taken far, far away and dropped in a forest but found its way back home? What about an elephant?

Last week the Kenya Wildlife Service completed the first of several phases of relocating 200 jumbos as much as 100 miles from where they were picked up. The controversial and very expensive project is one more attempt to “save” elephants by removing them from angry farmers, school children and people walking to church.

Well, we won’t know for a while. But … a couple don’t like their new diggs very well.

Two were killed in Kisii, a heavily populated city in exactly opposite direction from where they were relocated, and although they were “dispatched” by villagers before wildlife officials could identify them with certainty, there’s every indication they were from the relocated bunch.

Those ele would have walked about 50 miles through (human) enemy territory northwest having just been brought 50 miles southwest to the idyllic and peaceful human unpopulated Maasai Mara in the relocation effort. And frankly, whether they were from the relocated bunch or not, their journey from the nearest open reserve (the Mara) shows how capable they are of navigating human population centers.

And at the end of their journey you don’t hear cute little mews at your backdoor.

Pole pole I’m coming round to thinking ele must be culled. I’m not there yet, and I still viscerally resent the mostly southern African theory of “carrying capacity” and that anything that doesn’t meet the model should be eliminated.

(Not just ele, by the way, but Jacaranda trees, certain flies and spots on windows.)

But the situation in East Africa is growing intolerable, and intolerably expensive. KWS has moved the first 50 tuskers at an expense of about $3,000 per elephant.

That’s huge, especially by African standards.

All sorts of things are being desperately tried now to control this human/elephant conflict, from pepper spray, to scare crows, to moats and bullhorns.

The most effective way is already being used in southern Africa (where they don’t need it as much, because they kill their excess!). The seel-reenforced concrete spike barriers employed in Botswana around its national parks tourist camps work well. The problem is they are extremely expensive, too. Each roughly 4′ x 4′ block costs around $10.

That’s the cost in South Africa. First there would have to be a factory built to produce them in East Africa, or the additional cost of importing them to East Africa.

To surround the northern top cap of the Maasai Mara (the southern border sits on the Serengeti) you’d need more than a half million blocks and that doesn’t even take care of the many river boundaries where they wouldn’t work, the labor to do it, they maintenance and the possible environmental fallout of also impeding other wildlife.

And then, of course as the southern Africans would point out, what happens when the density of elephant is compressed to a level that starts to destroy the Mara ecosystem?

You see. The reason the ele are leaving their splendid protected reserves, is because there are too many of them already.

So any successful barrier or relocation effort could end up being counter-productive.

I won’t continue to the conclusion.

Marvel of the Mara

No, of course it isn’t. It is Kenya’s best game park, the Maasai Mara. So we ended our safari with incredible game viewing, and it was expected. But am I showing my clients the wilds of Africa?

The Mara proper is hardly a tenth the size of the Serengeti, sits right on top of it, and is the northernmost venue for the great migration. It has almost 4 times as much accommodation as the Serengeti, despite its much smaller size. So, yes, it can seem busy if crowded compared to the Serengeti.

For two intertwining reasons.

First, the Mara is the wettest part of the Serengeti/Ngrongoro/Mara ecosystem. And wet means more food at every level, and that means more predators and ultimate cleanupers.

Second, more animals means more visitors and the Mara is probably the most congested game park in East Africa. Lion brush aside your vehicle, vultures clip your canvas rooftop when landing, hippos block the road into your camp and crocodile lay eggs a few feet under your tent.

And rarely are you the only one snapping photos. I try very hard and do often succeed, but if you want to see the rhino, or the cheetah take-down, you’ll be sharing the experience often with 10-20 other vehicles.

But here’s the rub. Remove the visitors, the vehicles, the people, and I think it fair to argue very little of anything else would change.

So are we really experiencing truly wild and natural behaviors?

Yes. For the Mara. It’s as natural as garlic mustard taking over Yosemite or chronic wasting diseases menacing recreational hunting in Wisconsin. What I’m saying is that in the Mara it is a real balance of life as it exists there, today.

It is certainly not the way it was a generation or more ago. And it is certainly not the way it is in most other reserves in East Africa.

Even in the Serengeti, which shares a border with the Mara and several rivers, animals grow more suspicious of human visitors and their vehicles. But even so, these “wilder” behaviors in other East African reserves are far tamer than they were in Africa 50 years ago.

Then, African wildernesses weren’t as protected. People competed with animals for the same turf, and people are more clever. Animals were afraid of people, people would just as likely kill as preserve anything wild, and so wild things were harder to observe, less obvious.

So the complaint I have about this marvel in the Mara is the growing number of other visitors. And as a visitor, you have to decide if you want to see it all, rather easily and quickly, or prefer as I think I do the less congested wilderness.

This dynamic – the marvel of the Mara – has happened only in my life time. It’s something that I feel has been achieved at the loss of “wildness” which is still easily experienced in places like The Selous or the Serengeti.

But nostalgia may have gotten the better of me. Visitors may not seek wildness any more than they seek the remarkable beauty of a lioness cleaning her cubs, or tiny baby warthog racing after mom. And for all those wonderful experiences and so much more, the Mara is the place!

No Drought News is Not

It’s raining in the Mara; it should be: That’s not news. It’s not raining in northern Kenya; it shouldn’t be: That’s news. Go figure.

It’s raining in the Mara; it should be: That’s not news. It’s not raining in northern Kenya; it shouldn’t be: That’s news. Go figure.

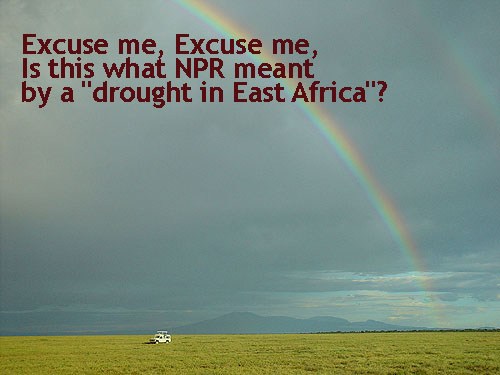

In between truly cataclysmic reports of America’s political constipation last week, many news sources were reporting on the “calamitous” drought in “East Africa.” One concerned consumer emailed me:

“My husband and I are scheduled to go on safari to [East Africa] in 3 weeks and are very concerned since hearing stories of devastation and the death of wildlife due to the drought. We are insured for the trip. Do you recommend we cancel and visit another time when conditions are improved? We have spent an awful lot of money and don’t want to spend 2 weeks in a dustbowl viewing dead and dying animals.”

My office explained it was raining in the Mara. The excellent Governor’s Camp there reported 85.5 mm of rain in June (3.37 inches), a little less than normal, but nothing to write home about.

There are three important issues here.

First, “East Africa” is a big place. When you include all of Somalia, as NPR did in its weekend reporting, the area is nearly the size of half the continental U.S.

There’s a drought in America. There are devastating tornadoes in America. Floods are killing people in America. Wild fires are forcing people out of their homes in America.

Dare you visit the Blues Festival in Brattleboro, Vermont?

Columbia University’s excellent climate reporting website shows the actual precipitation over the last twelve months. (To get the “loop” actually looping, you may have to click on “Precip Loop” in the left-hand blue panel.)

When corroborated with many other similar data sources, what we know is that overall “East Africa” has a pretty normal rain pattern for this year. Somalia and northern Kenya less than “normal” and much of the prime game viewing areas of Kenya and Tanzania normal or just slightly below.

That’s the first issue’s facts. I know in today in America facts seems to matter less and less, but I can’t seem to drop the habit of referring to them.

Second. Climate change is deeply effecting all the tropical regions of the world, including East Africa, more quickly and more extremely than in much of the world including America. This is because of the highly complex way that weather works at the equator. Even when you look up from the equator at the sky, clouds rarely move at all, the confluence of multiple jet streams and mixed up “corioloses” is one of the most complicated swirling and twirling air patterns on earth.

In a nutshell the result has been to make dry drier, and wet wetter. It’s the reason we do have “drought conditions” in northern Kenya almost constantly, interrupted by a season of devastating floods.

Three. And probably most important. The human catastrophe occurring in Somalia, northern Kenya and Ethiopia is hardly new. And the fact that it’s being reported as news is a sorry indication that we don’t care as much as we should.

Do you remember “Live Aid”? That was nearly 30 years ago. Things haven’t changed much since. Admittedly, dry is drier, and there are more people to feed, so famine is more likely and will now occur more often.

Do you remember “Blackhawk Down”? That was nearly 20 years ago. That’s when Bill Clinton let Somalia implode. It’s never come back together.

The human catastrophe in a part of East Africa is human made, not weather made. True, the desert has been growing literally for millennia from north to south on the continent, and East Africa is near the dividing line moving south. But desertification in Africa is not news, happens at a relatively slow pace and can be adequately dealt with by proper human development.

And fresh, good, potable water has been a growing catastrophe in Africa for decades. This, too, has been known for 20-30 years and there are ways to deal with it.

It is the politics of fear, egocentrism, greed and lack of compassion that has been growing at too fast a pace.

It’s raining in the Mara. You can proceed nicely on your safari.

Widely Wild Wrongly Written Wildebeest Writings

But I took this, this year, with my Cannon SureShot.

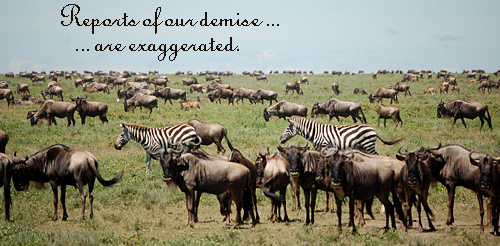

Many of you truly concerned wildlife enthusiasts have sent me the link to the bad BBC story claiming that Kenya’s best game reserve is in a tailspin. Thank you, but take a powder and lie-down.

The purported “study” by Joseph Ogutu at the University of Hohenheim is the second study by Ogutu on the Mara. His first purported up to 95% of certain animals had disappeared and was uniformly dismissed by scientists worldwide.

I found it interesting this morning that the branch of the university that Ogutu is supposedly registered with, has an “internet problem.” Linking to the Bioinfomatics Unit of the University of Hohenheim cited in the BBC report generates this message [poorly translated from the German]: “Because of maintenance work the Intranet and some other homepages are not available.”

Hmm.

Mara wildlife has declined, and local wildlife censuses have confirmed this, but nowhere near as catastrophic as suggested in Ogutu’s report. Ogutu told the BBC that Mara wildlife had declined by “two-thirds.”

Nonsense.

Here’s the truth. No one knows in any good scientific way. The Kenya Wildlife Service conducts wildlife censuses that are excellent, but KWS has limited jurisdiction in the Mara which is technically controlled by local county counsels. In fact as I’ve decried loudly before, the Mara’s catastrophic problem is management not an apocalyptic reduction in game.

At one point three separate entities were controlling what we call “the Mara” and they didn’t like one another. So it’s literally impossible to conduct uniform studies over the area. And to make matters worse, historically the data is equally terrible.

Ogutu did the worst possible research as a result. He picked and chose segmented area studies over 15 years, none of which were comprehensive of the area as a whole. Moreover, I’m certain in the weeks ahead real scientists will challenge much of his root data.

Ogutu had decided the Mara was in a tailspin even before he did this study. Last year when the area was just recovering from a three-year drought, he claimed half the animals in the Mara were gone by incorrectly citing a continent-wide study

from the United Nations Environment Programme and London Zoological Society which addressed the whole continent, not just the Mara.

There are good studies, particularly from the Frankfurt Zoological Society, on the biomass of the Serengeti and larger Serengeti/Mara ecosystems. There are also good studies on individual species, like lion and elephant and so forth. And unfortunately, we can only surmise by broad intersections of these individual studies what the situation is, in the Mara.

It’s OK.

It’s very threatened, perhaps more so than at any time before. This is mostly because of (1) weather, also closely because of (2) Kenya’s rapidly developing economy leading to human/wild animal conflicts, and interminably (3) the untenable way the poor reserve is managed.

But don’t write it off, yet. Kenyans are remarkably creative these days.

Ogutu is correct that there has been a significant decline in Mara herbivores, particularly with regards to the wildebeest migration. But this is not directly due to cattle grazing encroachment as he claims. It is because of weather. Two dynamics are at play.

First, the Serengeti just below the Mara has been much wetter than normal (as has the Mara) but while areas just immediately to the north and east have been much drier. Global warming at its best on the equator creates these weird and frighteningly small and distinct weather regions.

So while there were floods in the Mara, in adjacent cattle grazing Koiyaki and Lemuk private reserves, it was bone dry. In times of drought cattle tended by cattle owners over compete with wild game.

Second, because the Serengeti has been wetter than normal, the wildebeest have not needed to move into the Mara (the furthest northern part of their migration) with the same regularity as in the past. Historically the Mara was the wettest part of the Serengeti/Mara ecosystem. That definitely is changing. There will be less and less of the migration traveling into the Mara, now, with global warming.

The wildebeest population has remained constant at around 1.5 million animals for more than ten years. Ditto for the third of a million zebra.

So without intending to minimize the real threats existing in the Mara, let’s not exaggerate them, either. I wish Vanity Fair or the New York Review of Books would do a story. There is no new crisis in the Mara. Visitors today will notice little difference from ten years ago, except maybe with regards to the migration.

Rather there is a continuing decade’s long crisis we definitely need to do something about, which cannot exclude global warming. And there is an ever deepening crisis in the way we learn things.

Oh those Scandalous Wildebeest!

Reports in the media that the great wildebeest migration this year has made a wrong turn and surprised ecologists is absurd. There is nothing anomalous about the migration this year.

Reports in the media that the great wildebeest migration this year has made a wrong turn and surprised ecologists is absurd. There is nothing anomalous about the migration this year.

The East African newspaper reported Monday that “A change in the spectacular wildebeest migration schedule in the great Serengeti-Mara ecosystem has caught ecologists offguard.”

Using reports that seem confined to a luxury private lodge in Tanzania just outside the Serengeti near the Kenyan border, the article went on to say that 150 – 200,000 wildebeest were reported around this lodge in September, “never before seen.”

This was then picked up worldwide. Such reliable on-line sources for Africa as ETN headlined the same day, “Mystery as great wildebeest migration cut short in Maasai Mara Game Reserve.”

Stop! Stop! This is all wrong!

Now none of this current balderdash is as infuriating as the scandalous “Wildebeest Migration Blogpost” – which of this writing, by the way, hasn’t had an entry since June. That completely misleading blog actually comes out of a South African tour company whose principals are never in Tanzania. Figure that one. Practically everything in that blog is dead wrong.

SO beware oh yee of internet searches.

The main article which started all the nonsense Tuesday seemed to have been motivated by a single blog from &Beyond’s Klein’s Camp, a great private camp just east of the Serengeti and south of the Kenyan border. Their blogs have reported numerous wildebeest herds as early as September. But they’ve been going and coming, as is normal in a year of heavy rains.

This has been a year of heavy rains.

Deeper into the Mara, that is further north from Tanzania, many camps like Governor’s reported “best migration season ever” this year, which would normally mean Tanzania saw nothing abnormal at all.

What’s the truth?

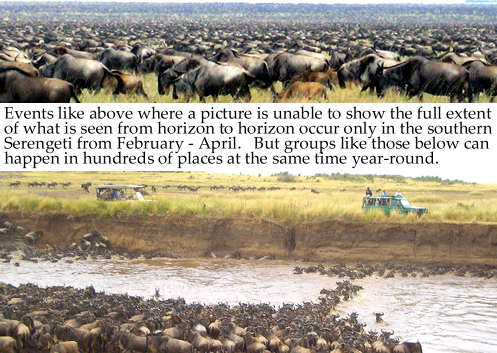

The truth is that it has rained so heavily this year, that there is good grass in many places that in normal years there would not be good grass. This means the migration is spread out all over the place.

Tourists – even veterans – tend to report they’ve seen a “great migration” when at best they can see only a tiny fraction of the herds. There are likely 1.5 million wildebeest.

When I sit atop Wild Dog Hill southwest of Ndutu in late March and look around me for 360-degrees over flat plains covered by wildebeest, from a horizon on the west that is probably 60-70 miles from the horizon on the east, we are probably at best seeing a quarter million. This scene only happens in the southern Serengeti from February – April if the rains are normal. Only a teeny-weeny fraction of tourists ever sees this.

The vast majority of tourists see “the migration” as large numbers of wildebeest moving across the plains or jumping over rivers, and these groups probably at most number a few thousands.

Smaller events like these can happen in a thousand different places nearly at the same time! These are usually in the last half of the year, mostly reported from Kenya’s Maasai Mara (because that’s where most of the tourists go). But these types of events can happen almost anywhere year-round depending upon the rains.

Wildebeest don’t have schedules. Unlike monarch butterflies or Wilson’s warblers, they aren’t triggered into migration because of changing daylight or diminishing temperatures. Unlike caribou or polar bears, they aren’t triggered into migration because of ice. They move to wherever they can get a good meal, whenever they can get a good meal.

It’s just that over centuries the rainfall has been more or less regular. (That, by the way, may be changing with climate change, but not enough yet to alter long-term statistics.) Normally, heavy rains fall on the southern Serengeti during the first half of the year, and heavy rains fall in the Mara (northern Serengeti) during the last half of the year.

So, normally, they move south to north around mid-year for the rain produced grass, and then return north to south at end-year for the rain produced grass.

This year there was a lot more rain than normal everywhere, and it ended later and began earlier. So wherever they moved they could eat. So they’d eat themselves out of one place, then race over to another. Then it would rain where they just were, so they’d race back. This is not unusual.

The reporter got charged up when he made the mistake of asking Tanzanian scientists what it all meant. In complete deflection of the facts, the Tanzanians basically said it was great … because the “unusual ecological change” meant there were more wildebeest in Tanzania than Kenya, and they just love to stiff their Kenyan counterparts.

For tourists, it was great everywhere! So don’t worry either if you’re a traveler or a lover of animals. Everything’s doing just fine.

At least this year.

The Mara: Tipping or Tentative?

I hate reporting a story like this, but it’s been growing in my conscience like mold on the wall. Time to disinfect.

“Scientific studies” in Kenya just don’t carry the weight of well-funded work elsewhere in Africa, particularly in the south.

Just a few months after rains returned to East Africa late last year, the Kenya Wildlife Service mounted an animal survey that began in Amboseli. KWS concluded that as much as 83% of Amboseli’s wildlife had been lost.

Click here to see the survey. Oops. Gone? It’s been removed. But aha! I saved the paper: click here.

All sorts of bigwig organizations participated in that paper, including some that are now criticizing it.

Evidence is growing that the survey was wrong. Not long after the survey suggested that most of Amboseli’s elephant and wildebeest had died, Cynthia Moss’ ATE

group reported that “most” of the elephant were returning, although with fewer juveniles. And only a few weeks ago, one of ATE’s researchers, J. Kioko, reported that “about 1000 wildebeest have arrived in the park.”

Now, this second damming report might be just as flawed.

The report was funded by the Africa-based International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and was published in the Journal of Zoology and essentially painted a catastrophic situation in Kenya’s Maasai Mara, claiming the reserve was on the brink of collapse.

The Mara Conservancy, one of the two authorities controlling the Maasai Mara, issued a stunning denial. The Conservancy called the report “false.”

The report put much of the blame on the explosion of Maasai homesteads in the “private” reserves that ring the Mara conservancies. Specifically, the report claimed there were only four homesteads in 1950 and that there are now 368. And in what I consider a gross indication of the report’s inaccuracy, it claimed there were 44 huts in 1950 and 2735 in 2003.

Homesteads, maybe, but huts are built and torn down weekly. The 1950 data wasn’t sourced, but had to come from colonial authorities, and native statistics in 1950 have been proved time and again to be grossly inaccurate.

Paula Kahumbu, Executive Director of Richard Leakey’s reputable Wildlife Direct organization, remarked as follows on one of the report’s huge claims of wildlife losses:

“For the life of me I cannot find the 95% decline in giraffe in any of the blocks – the greatest decline that I can find is in block 3 where numbers of giraffe decline from 37 to 12 individuals. That’s only a 67% decline.”

I’m not trained or blessed with enough time on my hands to wade through the competing reports to determine in any scientific fashion which are right and which are wrong.

But that’s not going to stop me from making a few conclusions that might help those of you interested in East Africa’s wildlife, or those who are considering traveling there.

First, why are things so confused? Isn’t science… science?

Yes to the second, but as the first, Kenya’s problem is unique; unique even to Tanzania, its nearest and most similar neighbor. The government of Kenya long ago divested itself of full control over a number of its wildlife reserves, including both Amboseli and the Maasai Mara, arguably the two most important ones.

These great tracks of national treasure were seconded to local authorities (Maasai county councils) who exacerbated the problem by privatizing their operations.

The federal Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) still has some authority in both areas, but the bulk of the authority, including reporting facts on a day-to-day basis, is left in private hands. Even anti-poaching patrols in the Mara are run privately, not by KWS.

And to make a terrible situation intolerable, in the last decade the Mara was divided into two separately operated reserves. One by the Narok County Council, and the other by a sister Maasai community, the Trans Mara County Council.

One of Kenya’s legendary safari guides, Allan Earnshaw, wrote recently for the East African Wild Life Society, “The root of the problem is the fact that whilst the Maasai Mara is called a National Reserve, it is in fact treated and run as a local asset by the two different local authorities.”

(Problem upon problem: I cannot link you to this article, because remarkably EAWLS does not publish anything digitally.)

But Earnshaw is right on. And it gets truly ridiculous, as is the case as I write at this moment, if you wish to visit the entire Mara (which isn’t very big, you could do it in a day), you have to pay two fees: two times $60, to cross the Serena bridge going from one half to the other.

Anti-poaching patrols and scientific study groups are similarly constricted.

Collection of tourists fees, scientific study oversight and anti-poaching are operated by private organizations, separately for the two halves of the Mara, but the building of tourist lodges is a federal decision.

So since 2005, “no fewer than 55 new camps and lodges have been built in the Mara.” In 1997, there were a mere 20 camps and lodges. Today, according to Earnshaw, “there are over 100 and counting – with a bed capacity for 4000 tourists.”

The confusion over the numbers of animals, and the numbers of tourist lodges, is because there is no single authority managing the Mara. Studies and revenue receipts contradict each other. Private companies, competing for business jobs, exaggerate their potential. There is no neutral authority overseeing all this.

This is a Ph.D study of mismanagement at the least. Can’t do that, now. But let me try to glean from this mess three simple conclusions:

The effect on the area’s wildlife by the last drought was not as bad as local “scientific” studies suggested.

It was still bad, but probably not worse than in previous droughts. And with time we’ll know this for sure, but even in this short period of time since the rains returned late last year, things look pretty good to me.

Second, game viewing is increasingly depressed outside the parks. If you want to see a lot of game, avoid the private reserves and stay inside the park.

(Necessary semantic clarification: The Maasai Mara is not a private reserve, it is composed of two separate (County Council) government reserves, but it is privately managed. But ringing the Mara as is the case with almost all parks in East Africa, are adjacent or near adjacent private lands with tourist lodges.)

&Beyond’s Klein’s Camp and the Grumeti Reserve camps outside the Serengeti are examples. Saruni, Sasaab, Elephant Watch Camp are others outside Samburu. Treetops and Kikoti outside Tarangire. Literally all the Bush ‘n Beyond camps, and Laikipia camps like Lewa Downs and Loisaba are outside parks.

This doesn’t mean they aren’t fabulous additions to a vacation with their own unique attractions. It just means if you aren’t close enough to a park to at least enter it during a day-trip, your game viewing will be depressed compared to being inside the park.

Third, privatizing management of national treasures like a wildlife park or national Park (as being considered in the U.S.) is nothing less than stupid.

It transforms good, neutral scientific studies into the components of a cost-effective business plan. It prostitutes moral authority with profit. The decline of American zoos, for instance, I place squarely on the fact that the vast majority were privatized in the 1980s and 1990s.

America, take note. Kenya’s greatest national treasure, if it is in peril, is because it was off-lifted into private hands.