Tanzania’s disgraced former Prime Minister launched his political comeback yesterday by vowing to push through the Serengeti highway despite environmental objections.

But in typical Tanzania PoliSpeak, Lowassa left open which route he supports. I think the man is on track to become the final power broker for how the highway is built and that he’s essentially going to put the route up for international auction.

As with everything in Tanzanian politics, a lot of reading between the lines is necessary. There is a possibility that Edward Lowassa is just a loose canon trying to avenge his disgrace, being carefully rehabilitated by power elites, or just blowing populist hot air.

Lowassa’s flamboyant political rally in Mto-wa-Mbu, specifically where the highway is scheduled to begin, came only one month before the national election on October 31. He is running on a small, opposition party ticket (Chama cha Demokrasia na Maendeleo, “Chadema”) which currently has only 6 of the 295-seats in Parliament and no national officials.

(Chadema may be the biggest threat to the ruling autocracy in Tanzania, although it’s hard to see enough victories in Parliament to impact the balance of power.)

Lowassa cannot run on the ruling party ticket, because he was thrown out in 2008. At the time he was the second most powerful man in Tanzania, its prime minister, but he got mired in one too many scandals.

He resigned as Prime Minister on February 7, 2008, after being implicated in a corrupt deal with the Houston energy firm, Richmond Development, where it was widely speculated he received enormous kickbacks for electrical services that were never delivered.

His resignation and that of other implicated ministers which immediately followed saved him from any formal investigation into the extent of criminality.

Making the Serengeti Highway a primary campaign position allies him with his former friend and now President, Jakaya Kikwete, who is also the man who forced his resignation in 2008.

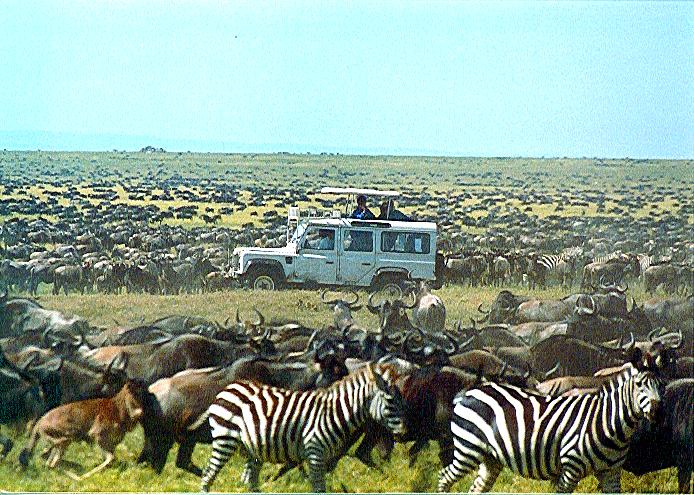

But unlike Kikwete, he hasn’t specified which route — north through the Serengeti or south outside animal reserves — he favors. And listening to him yesterday at his rally, you’d think the issue wasn’t whether to lay the tarmac north or south, but whether to build a highway for the common man or preserve lions for tourists to see.

“Environmental activism should change. [Activists] should not be more concerned by the welfare of the animals than that of our people who need development,” Lowassa shouted to the cheering crowd.

Lowassa began his career as the area’s police boss, and he remains very popular locally so is likely to win. His opponent is an evangelical minister whose main campaign issue is that the election, scheduled for October 31, should not be held on the Sabbath.

Lowassa is playing both ends of the field. He can win the election and still embrace either the northern or southern route.

And then, he will become the most prominent politician whose constituency is closest to the actual highway area. He will become crucial in any negotiations down the line.

I think this is what Lowassa is doing, sneaking his way into an issue that not even the ruling elite can control, one that is certain to ensure his political rehabilitation on the national level.

He’ll give Kikwete an acceptable path towards changing his own position, which is that the northern route is the best one, while ingratiating himself into the political elite once again.

Lowassa will be up for the highest bid. That’s the nature of the guy. So NGOs, start the fund-raising, because Lowassa’s victory will be a sure sign that the highway’s route is up for auction.