Sports hunting has long been characterized as a conservation tool. That is absolutely not the case in East Africa, where all trophy hunting should be outlawed.

Sports hunting has long been characterized as a conservation tool. That is absolutely not the case in East Africa, where all trophy hunting should be outlawed.

Kenya banned all hunting in 1977, then later allowed some bird hunting. But the other nations of East Africa promote sports hunting.

This article shows why sports hunting throughout all of East Africa should be banned. I think it likely with time the ban should extend throughout all of sub-Saharan Africa.

Botswana recently banned hunting, and Zambia recently banned the hunting of cats. I think it inevitable even the big hunter destination of South Africa will finally also ban trophy hunting.

But right now the evidence is so compelling to end hunting in East Africa, that’s where this article focuses.

The power of the sports hunting industry and the gun manufacturing industry cannot be overstated as we approach this debate. Sports hunting, even big game hunting in Africa, is far less contentious than gun control in the United States, for example. But the industries and lobby of wealth organized to promote gun ownership has virtually fused itself with the issue of sports hunting.

Americans constitute the largest single group trophy hunting in Africa. So American institutions, money and lobbying are integral to this African debate. “Americans are by far the most keen to spend around $60,000 on trophy hunts in Africa,” writes Felicity Carus recently in London’s Guardian.

The balance of American money and power supporting hunting is woefully unfair, and it isn’t just the NRA. Sportsmen’s Alliance and the National Shooting Sports Foundation are both funded by multiple large foundations whose donors are kept secret. Journalists shy away from reporting negatively about these monoliths and politicians give them a wide bay.

My intention, here, is not to take on sports hunting per se, nor gun ownership. The issue of big game hunting in Africa specifically has reached a uniquely critical threshold. In Africa – right now – big game hunting is a threat to conservation and rural development.

I fervently believe there are philosophical and ethical arguments against many types of sports hunting. But that is actually secondary to the more compelling reasons today in Africa that big game hunting should be ended.

The main reason big game hunting should be immediately ended throughout almost all of Africa is corruption and bad policy. The same reasons that conservatives use to deplore even humanitarian aid to emerging nations is grossly evident in Africa’s management of sports hunting, today.

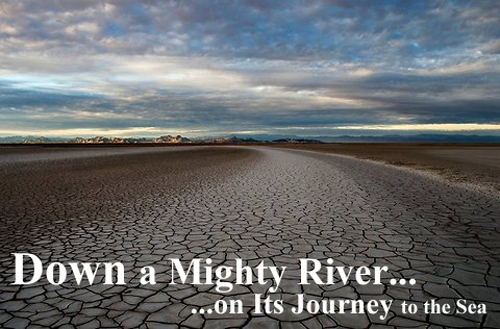

We’re reaching a critical point in Africa’s wildness. It’s a tipping point. The growth of African societies is exceptional, and basically good. Bigger human populations are developing at breakneck speed. It’s hard for an American to imagine how fast, for example, Kenya is developing.

Many of my clients are repeat visitors to Africa. It’s amazing to watch their jaws drop when they return after even as few as five years. Highways, factories, residential developments .. it’s an unending serious of hopeful and modern progress.

And at what cost? At the cost of the wild, of course. That’s not a surprise and it’s not new. But it is changing.

Only a decade or two ago, safari tourism was critical to the economic health of Kenya, vying with the production of coffee and tea for the top spot on Kenya’s GDP. Today, tourism overall in Kenya represents only 5.7% of GDP (2011) and arguably half that is non-animal, beach tourism.

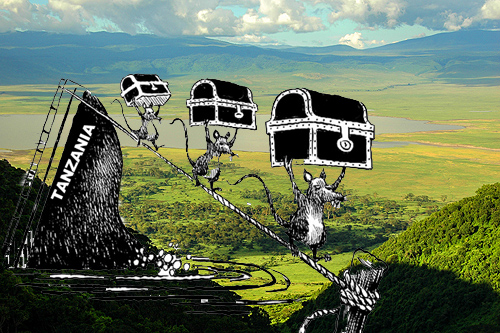

And while it’s likely Kenya’s tourism is falling behind other sectors of its economy because of recent terrorist acts, neighboring and quite peaceful Tanzania’s trends are even more exaggerate.

Tourism as a part of the Tanzanian economy is expected to drop to 7.9 per cent by 2020 from 8 per cent recorded in 2010. Like Kenya, by the way, it is likely that the single biggest growth within tourism in Tanzania is the beach, not animals.

This emphatically doesn’t mean that safari tourism isn’t growing. What it means actually is that so many other sectors of the economy, like oil production, are growing much more rapidly.

Oil is more important than lions. It wasn’t in Teddy Roosevelt’s day.

So the threat to the wild is severe in Africa. While the U.S. continues to debate whether the keystone pipeline should be laid over our wild lands, there’s not a moment’s hesitation about a new dam project cutting a chunk out of Africa’s largest wildlife park or slicing away protected marine environments for deep-sea drilling.

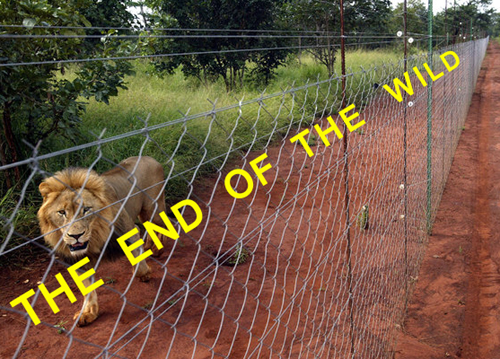

It is not surprising, then, that in most of the protected wildlife reserves in Africa, animal populations are falling, often because those reserves are either being reduced in size or because the pressures on their periphery are growing so great.

Sports hunting in Teddy Roosevelt’s day hardly disturbed the ecosystem. The technology of guns was far more limited than today. Animals in rural areas at home and in Africa were truly pests, because there were so many. Most sportsmen (including TR) killed very much for the meat that was essential food for them.

But as societies developed, as Africa is developing today, hunting too quickly began to deplete animal numbers (bison, pigeons, wolves, etc.). Wild environments were protected, and most hunting banned within them. And where it isn’t completed banned, it’s heavily regulated.

The reason is terribly simple: there’s little contest between a hunter and a wild animal, and over time, wild animals lose the number’s game.

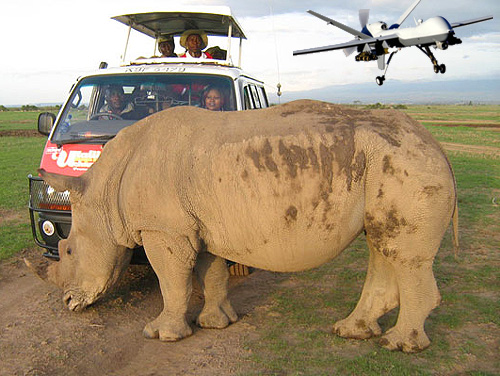

Africa has proved itself incapable of banning or regulating. Well managed (regulated) hunting is often considered a buffer against poaching, and so it was in Africa thirty years ago. The outskirts of protected areas were declared hunting preserves, and the symbiotic relationship with the protected area was a healthy one.

Along or within some protected areas in Africa hunting was used as the culling tool, as wildlife managers tried to establish a carrying capacity balance within an areas biodiversity. Hunters paid royally to kill “excess elephants” that lived at least part of their time in Kruger National Park in South Africa, for instance.

All of this worked, once. It doesn’t, now.

“Presently… the conservation role of hunting is limited by a series of problems,” according to two African and one French conservationists writing the definitive scientific paper against hunting published in Elsevier six years ago.

After meticulously detailing all the potential good that sports hunting in Africa could do, the authors take a fraction of the article to document how it sports hunting in Africa fails because of government mismanagement and corruption.

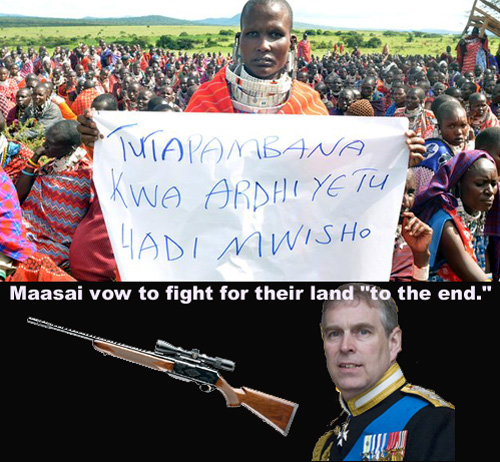

The list of corruptible acts linked to sports hunting in Africa would take a month of blogs to document. Whether it’s Loliondo in Tanzania, where land has been arbitrarily taken from both the Serengeti and Maasai farmers for Arab hunting, or ranches in South Africa recently unmasked as poaching rhinos, the list seems endless.

There are so many pressures on Africa’s wild, today, that it is nonsense to continue to allow a contentious one, sports hunting. The trophy hunting industry is tiny, in monetary terms, compared to overall tourism.

Its effect as explained in the Elsevier article is negative. So why continue it? Just so people can get a rush killing an animal? What other reason remains?

We are fighting the dam in The Selous, uranium and gold mining in the Serengeti, off-shore drilling in Lamu and highways through Nairobi National Park. There is absolutely little reason we shouldn’t also be fighting sports hunting, which provides even less benefit to Africa or its wilderness than mining natural resources or moving morning rush hours.

The time for Africa trophy hunting is over.

(Tomorrow, I discuss a very specific sports hunting issue that is now Africa’s hottest wildlife topic: should hunting lions be ended by listing them as an endangered species.

Stay tuned.)

It’s been a generation or more since certain animals considered vermin were proudly exterminated in the U.S., and the concept of bounty on nuisance animals is in welcomed, serious decline.

It’s been a generation or more since certain animals considered vermin were proudly exterminated in the U.S., and the concept of bounty on nuisance animals is in welcomed, serious decline.