Lazy guys, content curmudgeons, and sassy big boys told us some marvelous stories about the crater this year. In sum, better than expected rains have relieved some tension in the wild.

Lazy guys, content curmudgeons, and sassy big boys told us some marvelous stories about the crater this year. In sum, better than expected rains have relieved some tension in the wild.

Normally I find less than a few thousand wildebeest in the crater now at the height of the dry season, and these are often late birthed calves that missed the normal time to migrant and were then captured by the crater’s slightly better rainfall and subsequent scarce grasses.

This year rack up at least five thousand and it could be many more, and I’m sure that there were late birthed calves among these but it was mostly overly lazy males. After the males rut in May they sort of discard any more personal responsibilities, moving only when their belly tells them to. They lack the intuitive urge to migrate that the females have with calves in tow, and migrate only because grasses die.

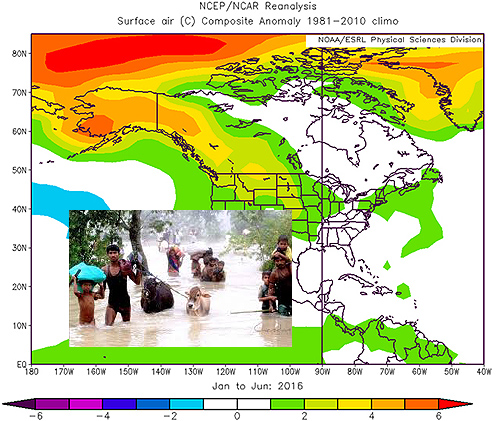

Apparently the grasses didn’t die as usual in the crater because of slightly better rainfall, and moreover, the Serengeti just beyond the crater’s rim is so terribly dry that they might have turned back when they hit the dust.

Unlike the Serengeti we experienced the last few days, the crater showed some rain with slight patches of green especially on its eastern side. The rivers were flowing more than normal suggesting the rim got even more rain, and the central lake was much larger than usual, displaying a good number of flamingoes.

So the male wildebeest decided heh, what-the-heck, there’s grass here! And they were joined by several thousand zebra that are driven more by available water than the wildebeest (who also need water, but are more finicky about the type of grass they eat than zebra).

So it was a bonus for us, but potentially a very dangerous situation for these male wildebeest if the dry season now resyncs normally. Between them and the wonderfully green Mara far to the north where their brides and children have gone is one of the most desiccated Serengeti’s I can remember.

One of the first things we saw the first afternoon in the crater was a pride of lion finishing off a buffalo kill. (By the way, it was right at the edge of one of the designated picnic sites!) That was cool enough all by itself, but more telling were two big, healthy male elephants who had wandered into the area.

These old curmudgeons weren’t up to much of anything, displaying vast amounts of boredom. They sucked in great amounts of water and then let it dribble out or squirted it in funny ways all over the place, obviously not in need of a drink.

When this game got tiresome they started what I can only describe as trunk yoga. Contracting their trunk upwards, it spiraled into a corkscrew and for obviously no reason.

At first they didn’t seem the least interested in the lions and their kill hardly 40 meters away. But after they’d cycled through their list of personal games, one of them turned towards the lions and froze before a slow, lumbering towards the kill.

Most of the lions scattered, but the one big female whose belly exceeded that of any of the others, stood her ground and growled.

The 6-ton ele hesitated momentarily, then lowered his head and moved forward.

She growled some more.

Heh, what-the-heck, he seemed to say as he flapped his ears, I made my point! And he lumbered away. All in all it was just an old guy, very well fed, with a lot of time on his ears.

This morning just after dawn we followed a bunch of excited hyaenas as they headed towards a big family of buffalo. Having last March just watched such as situation ending with a dozen of these monsters tearing apart an old, sick bull, I wasn’t about to leave.

But this time it was different. The family had dozens of youngsters and almost as many newborns. I noticed that one group of hyaena was actually cleaning up the after-birth, while others were testing the health of the newborns with quick little sorties into the herd.

Buffalo birth year-round and like elephant tend to abort when conditions are poor. That’s why we don’t usually see a lot of births in the dry season, but this dry season is obviously not so dry … at least here in the crater.

Normally the big males of the family guard the rest, but heh, what-the-heck, it was such a beautiful day the males had disappeared somewhere! Later we’d find them lulling about in mud and water chewing their cud near a wonderful patch of green grass. So it was the mothers who were now darting back at the hyaena to protect the youngsters.

I’m sure I’ve anthropomorphized the couple days in the crater a bit more than I usually tolerate of others, but it was a mostly happy situation, with the crater more beautiful and full of animals than is normally the case in the dry season.

Anomalous seasons have a potential, though, to turn ugly. The thousands of wildebeest that elected to remain behind in the crater and not migrate, or the many new born buffalo who need several months of voracious eating to grow strong enough to survive, have hung their fates on the hope the crater won’t turn as dry as the neighboring Serengeti.

Normally, rains don’t return before November.

But the wild often predicts outcomes better than meteorologists. Climate change is confusing weather patterns all over the place. Perhaps this year, in this one place, it will all be for the better.

Sometimes helping animals is not … helping animals. Three Connecticut women through a crowdfunding campaign have raised nearly $300,000 to supply water to animals in a drought-stricken area of Tsavo in Kenya.

Sometimes helping animals is not … helping animals. Three Connecticut women through a crowdfunding campaign have raised nearly $300,000 to supply water to animals in a drought-stricken area of Tsavo in Kenya. The success of childhood education is directly the result of how much tax payers will pay and how good the government is that implements it.

The success of childhood education is directly the result of how much tax payers will pay and how good the government is that implements it. Global conservatism will fail and Mali will soon provide the evidence.

Global conservatism will fail and Mali will soon provide the evidence.