Today was my “longest, hardest” day and always among its best. After ten hours we’d seen so much that the exhaustion wasn’t from the bumps but the sights.

Today was my “longest, hardest” day and always among its best. After ten hours we’d seen so much that the exhaustion wasn’t from the bumps but the sights.

Lots of people go to Olduvai Gorge when leaving Ngorongoro Crater, just as we did. And a few of them then continue to the site where Zinj was found, and fewer still continue as we did to the mysterious Shifting Sands.

I won’t give away the secret as to why these seven large hills walk themselves across the grassland plains, sometimes 20 meters a year, sometimes 200 meters. And we were further surprised by the arrival of some legitimate Maasai warriors who bumbed some water off us.

But very, very few people then know how to continue off the tracks altogether into the southern grassland plains between Olduvai and the Lemuta Kopjes. Two weeks ago the plain was filled with wildebeest. Today it was nearly wildebeest empty, because it had dried out.

But there were still literally tens of thousands of Thompson’s Gazelle. These beautiful plains creatures don’t migrate; they don’t have to. They eat the roots of the grass, and they rarely drink after suckling and then it’s usually for salt, not water.

But the unexpected twist to the day game when our lone two vehicles on the plane were intercepted by a white Toyota sedan car!

It was a German couple trying to drive themselves, and they were understandably lost. I was beside myself with anger and worry. The last thing East African tourism needs is a reported lost of two casual tourists.

They were using a map that was about 40 years out of date and large enough to direct them to Morocco, in other words, useless. They had come from a cheap camp in the northern Serengeti and wanted to go to Lake Natron.

They had missed their turn three hours before. We explained all this to them and told them the safest thing to do was to continue in the direction they were heading, since that was only two hours from Ngorongoro, and they were at least 6 hours from where they wanted to go.

But now, the woman driver said, they didn’t want to “go back” to Ngorongoro. After some questioning, it seemed they were reluctant to spend the extra $100 in fees it would cost them to reenter the Conservation Area.

I offered to give them the $100. As I said the last thing I want is for some tourists to hit the headlines as having been lost in the Serengeti.

But she refused, and there was nothing we could do. They turned around and headed back to where they’d come from, and we continued on our journey onto the Lemuta Kopjes for lunch.

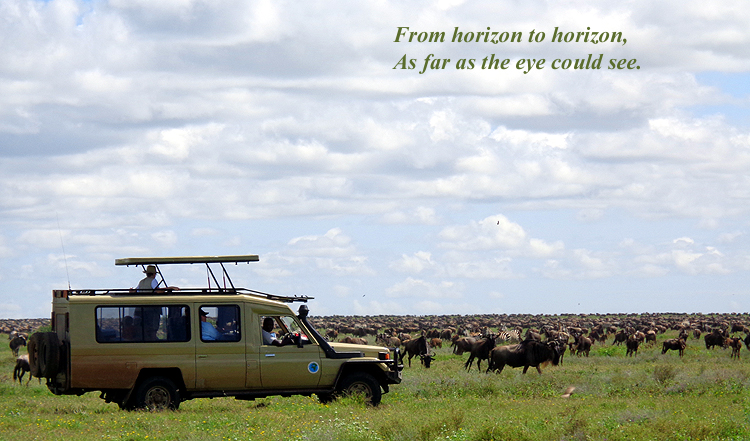

And right after lunch we intercepted the herds. It meant they had shifted about ten miles west of where I had seen them two weeks ago.

Understandably, people think the “great migration” is some strictly defined circle of movement, but of course it isn’t. Although wildebeest can’t stand still and will act like they’re moving all the time, if the grass is good, there’s no reason they need to move.

And the grass was phenomenally good. Today the migration is mostly in a rectangle, 40 x 20km that begins just west of the Lemuta Kopje and angles southwest to the Kusini Plains at Hidden Valley. I’d dare say that probably half or more of the 3 million animals currently composing the wildebeest, including young and zebra, are in this rectangle.

It is a sight to behold. And for the first time in nearly 12 years, Hidden Valley is once again open to us, the rhinos that were reintroduced here considered totally acclimated.

So we gingerly slid the cruisers into the valley to watch a large female cheetah stalk Grant’s gazelle. To no avail, as is the case with the majority of hunting attempts, but still a wonderful drama.

We set our elaborate breakfast, the best in all of Tanzania prepared by Ndutu Lodge, off the edge of the herds to avoid some flies. But even as we were eating, the herds started to envelope us.

We headed back to the lodge about six hours after we began, stopping to watch a magnificently beautiful and very full lioness grudgingly lift herself and her belly out of the grass to look quizzically at a line of wildebeest passing her bye.

She was just too full to hunt but too young to go back to sleep!

There is no natural spectacle on earth as great as this. I’ve been so fortunate that it has continued and prospered even during my forty years of guiding. I just hope that it will be so for the generations to come!