Why do so many safari travelers want to “see a village?” A Paris exhibition may help explain the ugly urge of many travelers to witness depravity.

Why do so many safari travelers want to “see a village?” A Paris exhibition may help explain the ugly urge of many travelers to witness depravity.

The market for village visits is so strong that even today, when traditional villages just don’t exist, they are being reconstructed, and thousands of visitors return from Africa every day believing they have seen “an African village” in exactly the same way conservatives leave church each Sunday believing Satan is a Muslim.

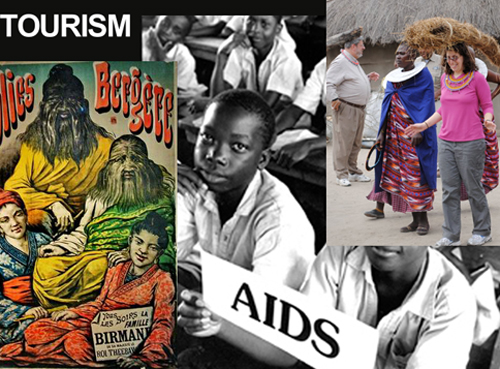

In the early boom days of photography safari travel (1960s and 1970s) “visiting a village” was an absolutely essential ingredient of any trip and I admit having arranged hundreds. “The Invention of Human Zoos” is a brilliant exhibition in the new Quai Branly museum that helped me to understand why.

“Act I” of the exhibition chronicles the excitement and amazement of Europeans who “discovered” such new and different peoples around the world starting in the 15th century. This “otherness,” as the exhibit calls it, was a driving force for early exploration.

Brazilian Tupinambas prostrating before Henri II in Rouen in 1550, Siamese twins in the Court of Versailles in 1686, Inuits overdressed before Frederik II in Copenhagen in 1654, and the famous “Noble Savage” Omai that Captain Cook brought to England from Tahiti in 1774 were some of the first and most famous.

There was no community exhibitionism in these early moments. It was just exhilaration at finding something so different from yourself! I hope this at least partly explains myself as a young “explorer” anxious to show clients African villages in the early days.

Omai was real; Kenyan villages in the Northern Frontier were real in the 1970s.

As the age of exploration matured, “Act II” of the exhibit details how this surprise at “otherness” grows defensive. Surprise doesn’t last. The reality sets in that this “otherness” isn’t very pleasing, because it’s filled with misery. But what to do? Go out and civilize the world when we’ve got so many problems to deal with here at home?

So “otherness” becomes “wrong” or “bad” or “evil.”

Circuses, traveling villages and freak shows worldwide marketed this rationalization by “blurring the difference between the deformed and the foreign.” Soon “physical, psychological and geographical abnormalities” sold tickets.

By the 1980s and certainly 1990s Africa was developing as fast as information technology. Primitive people weren’t primitive, anymore. But primitive and “savage” and “diseased” and “deprived” were the “physical, psychological and geographical abnormalities” that could still get tourists to pay.

So easily predicted these “villages” suddenly existed right next to very swank tourist lodges and camps. “Maasai villages” which in their original form never existed longer than the rains which fell on them for a single season, suddenly were in place for decades.

“Act III” of the exhibit describes the Crystal Palace, Barnum and Bailey, Paris Folies Bergères and Berlin’s Panoptikum where visitors are thrilled by “acts of savageness” from supposed aboriginals, ‘lip-plate women’, Amazons, snake charmers, Japanese tightrope walkers and oriental belly dancers, all of whom were “made-up savages” – professional actors, not real individuals.

Exactly as in Africa, today.

One of the real catastrophes this produces in Africa is that real depravity is created where it would otherwise not exist. When traditional villages moved regularly, as most did and certainly the Maasai and Samburu always did in the early days, opportunities for disease were lessened.

Imagine today’s so-called “Maasai village” outside Samburu Lodge or Serena Lodge after one year, two years, five years and then ten years without adequate septic systems.

(The final “Act IV” is more oblique and less relevant to Africa, I think. The extreme circus and freak show begins to merge “otherness” with physical abnormality. Indeed, the rise of Felini may be an important phenomenon worth examining, but its relevance to visiting a village in Africa is slight.)

There is, however, an Act IV today in Africa.

There is this inexplicable, basest urge by travelers to Africa to see “primitive” and “depraved” and the market reigns with these reconstructed villages more than ever. If there weren’t tourists paying to see them, they wouldn’t be there.

Thousands of safari travelers, egged on even more by immoral tour companies, regularly “want to see a village.”

What do travelers really mean when they ask for that? What they mean is that they want to see poverty, disease and depravation. In a nutshell, suffering. First off, why the hell would you want to see something like that? To disabuse yourself that it might not be true?

Alas the danger with that generous presumption.

Any half educated idiot walking into one of these should be able to tell by the facility of languages the “chief” commands, the perfect and untattered costuming, rushed routine and proforma narratives, that this is a show, not a lifestyle.

So that at least subconsciously the visitor can return at least subconsciously unconvinced that suffering exists. Or has to. Or that he has any responsibility to end it.

I was absolutely incensed recently by the “Mad Travelers” Kevin Revolinsk’s “Visit to a Maasai Village”. It’s below disgusting; it’s despicable. Yet this is a popular guy, widely published and validated by much of the established media like the New York Times and National Geographic.

And I’m sure there are many more examples as Revolting as Revolinsk.

Don’t be fooled, traveler. The misery is there, beyond your imagination. But it doesn’t exist in the flies unnecessarily flitting on the poor little kid’s face, but with the internal pain of the mother who plasters a bit of cow dung on her child’s head just before the tourists arrive… because she can’t get a job in the city.

Let’s end Act IV.

Guess I was one of the ‘idiots’! After reading your blog today I feel quite guilty about contributing to the poor lifestyle of the those living in the Masaii village we encouraged you to allow us to visit. I guess on future safaris your guests should be encouraged to read this blog before making plans to visit.

Hey, easy there, Jim. I hear you on this subject and couldn’t agree more. In fact, I thought that was the point of my post – it’s all a horrible show, going through motions, telling tall tales. The camps pressure tourists to attend, the government moves people out of potentially profitable nature reserves and then pressures them into a village scheme on the perimeter. Just like you yourself in your younger days, tourists are curious, they do want to see “how other people live.” Also, they are naive, on vacation from their own insular lives not having the benefit of living for years in these places as you have. However, I don’t think anyone in our group walked away thinking how quaint this was. It was miserable. But so was Nairobi. Getting that village woman a job there in many cases may be a lateral move.

I don’t know the solution to all this misery, but as I see so many self-sustaining aid organizations camped out in Africa, I suspect they aren’t getting anywhere near a solution and likely don’t intend to. (think Mother Teresa as explained by the late Christopher Hitchens) And we know how much we can expect from just about any politician, local or otherwise.

If the snarkiness of the post offended you, I apologize, it was the way I channeled my disgust. But I apparently failed to get my point across. These are blogs, not static articles, and as you can see from the comments on that post, they can function for constructive conversations on the matter or just angry exchanges. I’d welcome your input if you were so inclined, and would be happy to link to whatever posts appropriately address the “village visit” issue. Don’t hate, educate.

And I don’t mean to incense you further, but Revolting as Revolinski may end up on a t-shirt over here. 😉

Peace,

Kevin

Jim–another insightful observation/conclusion on your part. After visiting a village once I wondered how an educated Masai “village guide” could seem so happy under village conditions. Education and poverty/squalor just do not seem to fit side by side. Thanks for another good lecture.

I guess I’m an idiot too. You took me and my friends to one of these staged villages in 1997.

Larry –

Mea Culpa. It’s taken me a long time to formulate these opinions. You’re no more of an idiot than me. – JH

Hi Jim, thanks for your thoughtful post. My recollections on visiting one of these villages: gratitude that the inhabitants invited us into their historical culture. I was curious about the families, about how the home was constructed/laid out, about the relationship among the people. I thought it was instructive. I hoped our tourist dollars would help them. I hoped they did not feel demeaned by our visit. (I know the actors in Colonial Williamsburg are just portraying what it was like during that period… I kind of felt the same visiting an African village.)

It’s best to avoid them, but if not, we let the clients know that this is a “tourist” village (outside crater ie), not the real deal.

A village visit, if well planned, can be a very rewarding aspect of a safari. The village of Mto wa Mbu offers a very nice guided walk into the shambas where local crops are being grown and harvested and to a school and the medical clinic. It also includes a visit to a wood carvers guild, to a Tinga Tinga art shop and to a local beer brewing establishment. It’s a good educational experience and provides the guides with both a bit of income and a realization they have something special to offer visitors.

Some of the Maasai villages on the tourist routes have become tourist traps. These are to be avoided. However, they are some good and positive opportunities elsewhere. You just need to know which ones to visit.

Dick – Glad you brought this up, but what you describe I think in the vernacular is a “town visit” not a “village visit.” Similar to Ngesi by Arusha or Tloma by Gibb’s Farm, these are truly interesting and informative of contemporary African society, not charades of traditional bush lifestyles.-JH

Hi, Jim. Couldn’t resist writing on this one! Since you and Kathleen visited us, we started a Zulu Village Safari. It was at the suggestion of a guest who asked if someone could take her into the village so she could meet some of the local people. She even gave us the name! It is a walking tour led by a qualified guide who takes guests to a typical homestead (no actors), a school, the local clinic or the historic St. Vincent’s Church (Anglican) or whatever their interest and always visits a Sangoma (diviner). It truly is authentic in every way. Read more about it under Zulu on our website: http://www.isandlwana.co.za. The people visited are given a donation by our guide which comes from the reasonable fee charged the group (regardless of number). They are happy to get the income and are very proud to talk about the culture and customs of the Zulu people. So, while it is apparently different in many places, I can truthfully say we have a real-life experience here with no theatrics or showmanship. Best wishes, Pat

Thanks, Pat. See my reply to Dick Mills above, as this is similar and sounds terrific. – JH

Thank you for being thoughtful, sensitive. I believe that social interaction during international travel (i.e. visits to Maasai “villages”) is a 2-way street; both our hosts and we learn about each other. Worrisome to me is that we, as international travelers, perpetuate the stereotype of the Ugly American.

Very important discussion. I remember years ago in Kenya there was a place called Mayers Ranch on the way to Naivasha. It was clearly presented as a cultural experience created for travelers but had a great deal of authenticity and was respectfully done. I don’t know how the finances worked, but it seemed to be a decent, undisguised interchange between hosts and guests. The Maasai culture is fascinating to visitors, and it is worth learning about, even though it has changed so drastically. There may be ways to create an experience this so that neither side is exploited or misled.

Dear Jim,

Very interesting – I’m finding myself agreeing and disagreeing with you … Firstly I agree; with due diligence village visits can be made in a mutually beneficial way but it needs a lot of working at –and that’s what I do, though basically I think responsible tour operators are pissing in the wind.

But, if tourists pay to go to those mainstream touristy villages, so what really? I find “poor people tourism” as disgusting as you perhaps (Oh My God Elma look at the flies on those kids!!!” Click click click) but I think some of the “respect for local culture” stuff is taken too far. Tourists have money, the locals don’t see enough of it, village visits are a way of trading what you have for what you need. And those flies are real and on every Maasai kid in every boma in Kenya and Tanzania as you must surely know so they’ll be there whether tourist visit or not – see my fly trap project by the way on our website.

From JH – No, Chris, that’s an essential point I’m making. Most of these villages are NOT real. Traditional Maasai and Samburu villages moved every 4-6 months. One of the reasons — maybe the primary reason — these do not is because tourists pay to see them. And when they don’t move, they get dirtier, less healthy less real.

But here’s the thing. Tragically, it’s rarely the whole village that benefits. And I guess that were it the whole village that benefits you might also see the worthiness of the arrangement. No? Just the same with the larger scale scenario where the Maasai have not been particularly good at getting a fair share of the tourist revenue – some of the big guys have – but the most of them remain poorly served by others’ exploitation of their resources. And that is true of those village visits you cite.

So would those tourist attraction villages be better off or worse off if all tour operators stopped visiting them? I’d suggest worse off, and some lodge owner would reap the benefits by building himself a fake village by his lodge and staffing it with non-Maasai dressed up in red blankets – just like at Mara Sarova. I’ve gone on far too long already….

Happy New Year

Chris Morris

Director IntoAfrica UK Ltd

Fair-trade treks and safaris in Kenya and Tanzania

This is really interesting Jim. We visited a village in Tanzania and I did find it interesting, but you had warned us of some of the downsides, and these downsides were also very evident when we were there. Thank you for posting this so that people going on safaris without such a wonderful guide also get to hear about the issues involved with these villages. Having been to one, I can say that I wouldn’t go again or recommend it to others.

Hope you have a wonderfun 2012!

~Emily~

HI Jim,

This is very interesting – 1. Are tourist visits the only reason Maasai villages are not relocating after every 6 months i.e. since not all villages are visited by tourists do those that are not visited still move and those that are visited don’t? I suspect other reasons like reduced land and lifestyle might be playing a part. Do tourists have a prior knowledge of the sqaulor they find in the villages and how do they feel after the visit and lastly – which memory lasts in their mind, does the woman applying cow dung on her child bear responsibility? Do tourists only visit dirty villages? This might help us shape the people to people interaction for the future.