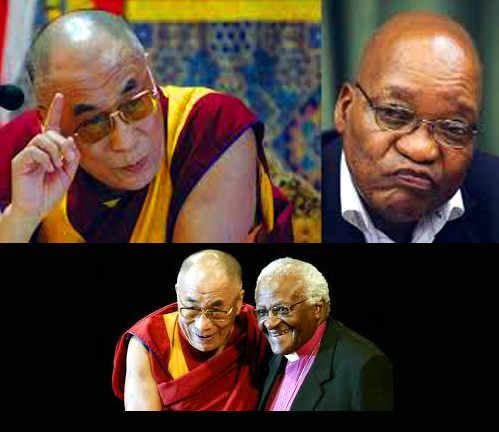

In an incredibly sycophantic move, South Africa’s president Jacob Zuma has denied the Dalai Lama a visa to attend a convention of living Nobel peace prize laureates in Cape Town.

In an incredibly sycophantic move, South Africa’s president Jacob Zuma has denied the Dalai Lama a visa to attend a convention of living Nobel peace prize laureates in Cape Town.

The convention was supposed to begin a week from today, but Late last week the laureates announced they were suspending the October 13 get-together and relocating to a yet unnamed country.

Cape Town Mayor Patricia de Lille said her government “has embarrassed the country.”

The laureates decision not to go to Cape Town followed the South African government’s refusal to elaborate on why the Dalai Lama was not given a visa. Fourteen of the 21 laureates sent a letter to President Jacob Zuma asking him to reverse his decision.

The initial decision to hold the convention in Cape Town, which would have been the first time in Africa, was a coup for the wildly popular Desmond Tutu, himself a Nobel laureate, who was instrumental in ending apartheid.

The ending of apartheid was the reason that Nelson Mandela, and at that time the president of South Africa, Willem de Klerk, shared the 1995 prize.

“I am ashamed to call this lickspittle bunch my government,” Tutu said in a statement.

This is actually the third time that the Dalai Lama has been denied a visa. The last time was for Tutu’s 80th birthday celebration.

China and South Africa have a very close relationship, and interestingly, it is less because of aid and investment than trade. South Africa is China’s leading trade partner in Africa.

China has publicly promised to lobby for more power in the UN Security Council for Africa. Given the political turmoil in Africa’s other powerhouse countries, Egypt and Nigeria, any such aggrandizement would likely benefit South Africa.

China has often snubbed the world prize, as a number of prominent and usually dissident Chinese have been made laureates.

Most Chinese believe it is a political tool, and as such, South Africa’s president’s refusal to embrace it should be seen as strictly political, say the Chinese.

One might also bring up sour grapes. Jacob Zuma is one of the most corrupt and least loved of South Africa’s big man politicians. Many in the country wonder how he has managed to stay in power.

He’s received none of the multitude of accolades and awards that many of his comrades-in-arms against apartheid, like Mandela and Tutu, have.

What perplexes me is how younger South Africans don’t seem to care to the extent I thought they would. Their lives are getting better, however incrementally, but key economic indicators like the spread between the rich and the poor is growing.

I suppose like at home, war fatigue has spilled over into political fatigue. Your average Joe has become exhausted by being fed up.

And so long as things on a day-by-day basis don’t seem to get worse, major if immoral power policies leading to oligarchical control just don’t raise enough ire.

It’s called the curse of apathy.