Obamacare is about to have a profound effect on American tourists who purchase travel insurance. But first, the truth about travel insurance:

Obamacare is about to have a profound effect on American tourists who purchase travel insurance. But first, the truth about travel insurance:

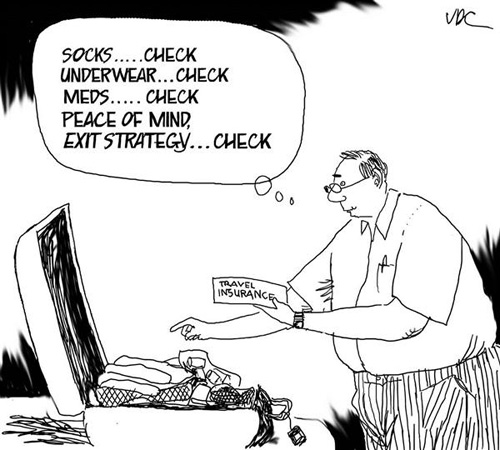

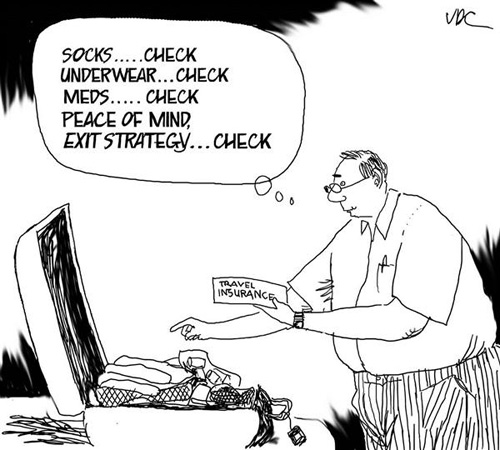

(If you know everything you care to know about travel insurance, already, skip down to the little cartoon to get to the meat of this blog, how Obamacare will effect your travel costs.)

Like every kind of insurance you buy in America for yourself or your household, multiple companies are involved, and multiple companies get rich off your premium, which is expensive. A good contrast with us is Britain.

Britain’s single-payer health insurance system, as well as one of its travel insurance systems — both provided by the government — cost individuals using them a tiny fraction of what American consumers pay. A Brit can cover himself for all the normal travel hazards American insurers include for about £75 annually for all their trips (about $120).

Whereas Americans must pay insurers approximately 5-6% of their desired coverage limits per trip.

Most travelers who purchase travel insurance do so for the component of coverage that will repay them the loss they would otherwise suffer if they must cancel after their nonrefundable payment deadline. And as you know payment deadlines with travel are well in advance of the trip.

The variety of conditions that apply to this is huge: all companies will repay you if you must cancel because you suffered an accident. The increased benefits from that point — say because you fell ill due to a pre-existing condition, or because your parents fell ill, or because of a terrorist incident, or because the travel company holding your money went bankrupt, or because you had a business reversal, or … for no reason whatever – are all available at higher premiums.

Premiums start around 3% of the amount you choose to cover yourself for. Average premiums are around 5.5%. Coverage for “cancellation for any reason” can exceed 25%.

Americans spent nearly $1.8 billion on travel insurance in 2010, up from $1.6 billion in 2008, and $1.3 billion in 2006, according to the US Travel Insurance Association.

But USTIA may be low-balling the amount: The IBIS research organization reported last month that it expects revenue will exceed $2.7 billion within five years.

It used to be that the bulk of sales came from older travelers concerned with aged parents, but that’s changing dramatically. I’m personally amazed that current research suggests the largest single demographic is 18-34 year olds.

This likely is the result of so much educational exchange abroad, which requires mandatory and considerable insurance. Underwriters, however, are suggesting more varied reasons, including aged parents from a generation whose parents were much older to begin with.

The usual way a traveler purchases insurance is from the same source from which they purchased the travel: The travel agent or tour operator.

The first level of commission earned by that agent or tour operator, the final seller, is around 30%. Yes, you read correctly, nearly a third. More often than not and particularly with unbundled homogenous products like cruises and airline tickets, the amount the agent earns from selling insurance rivals or exceeds that earned from selling the actual travel product.

But that’s only to the final seller. Everybody in the chain of sale earns well.

TravelGuard is one of the oldest and most respected travel insurance companies. Our own experience with it over decades has been positive.

But TravelGuard sells its policies in bulk to “National Union Fire Insurance Company of Pittsburgh, PA” which is actually located adjacent its parent company in New York to whom it resells its bulk purchases from TravelGuard. Its parent company is AIG.

Ever heard of them?

AIG is the principal global company underwriting travel insurance. American Express is number two. You will not see either of their names on any policy you’ve ever bought or ever will.

I’m not proud to say that in all the years of selling travel I’ve always cringed a bit while also biting my tongue when selling travel insurance. I understand entirely the “peace of mind” it affords the traveler, but it’s a royal ripoff.

Not for that ad hoc traveler who just happened to buy a big trip for the first time in her life just before her folks died. So individually, it’s hard not to recommend.

But for the common traveler who after retirement takes a couple trips annually for maybe 10-15 years, he’s gambling that one in a dozen will result in a need for unexpected cancellation. That seems like a reasonable number, but I doubt it.

Figures are near impossible to come by. The United States Travel Insurance trade group claims its surveys indicate that 1 in 8 adult travelers had issues that lead them to cancellation, and that about 1 in 6 actually filed claims.

But that’s the rub. We don’t know how many claims are paid, how many denied, how many negotiated. The travel writer Damien Tysdal recently listed “six” common reasons that travel insurance claims are denied, suggesting quite a few claims are ultimately denied.

I know that AIG got a bit of egg on its face for financial derivatives, but I got to think that travel insurance isn’t quite as tricky for them.

So how is Obamacare going to effect all this?

So how is Obamacare going to effect all this?

Travel agents who have been routinely selling travel insurance, such as EWT, were contacted this week by salespersons with the travel insurance companies. These were supposedly confidential calls to advise travel agents that the Affordable Care Act may disqualify them from selling future travel insurance.

It boils down to provisions in the act that limit all insurance by secondary agents to sales by state. So if you’re a travel agent in New York, you should be able to continue selling travel insurance to your New York customers, but not to anyone out of state.

EWT like many companies has a nationwide client base. Although the rep contacting us said the issue is “still with legal” and that they are “looking for loopholes” it sounded pretty certain: travel agents will now only be able to sell travel insurance to people who reside in the same state that they do.

Here’s what I think will happen:

Travel agents will be cut out of the loop, just as airlines and hotels cut them out more than a decade or two ago. This will mean that consumers will increasingly buy travel insurance on the internet.

And – as with all Obamacare – travel insurance costs ought to come down. In part this will be because more of the sales will be individual online sales, and this will generate more competitive pricing. Right now I think travel insurance pricing is elevated because of the dynamic of travelers buying their insurance from the travel agent who sold them the travel product.

So basically it’s good news for consumers, bad news for travel agents.

And I – at least – won’t feel so guilty, anymore!

Yesterday’s deadly grenade attack in Arusha isn’t simply an indication of escalating religious tensions in Tanzania, but of the same escalating individual malevolence evident in the Boston massacre.

Yesterday’s deadly grenade attack in Arusha isn’t simply an indication of escalating religious tensions in Tanzania, but of the same escalating individual malevolence evident in the Boston massacre.