By Conor Godfrey

Last week, Greenpeace shadowed an unlicensed 120-foot Russian Trawler off the Senegalese coast.

Ships like these often pull in 250 tons of fish a day by dragging 700 meter nets behind them. Some of them use incredibly damaging bottom trawling and other techniques that increase hauls while destroying marine habitats.

To put the effect of these super trawlers in perspective, allow me to quote a few statistics from the Greenpeace report on illegal fishing published last week:

1. “It would take 56 traditional Mauritanian pirogue boats one year to catch the volume of fish a [super trawler] can capture and process in a single day.”

2. “The amount of fish discarded at sea, dead or dying, during one [super] trawler’s fishing trip at full capacity is the same as the average annual fish consumption of 34,000 people in Mauritania.”

In short, bloated European fishing fleets have already overfished their own territorial waters, and are now taking advantage of poor African countries inability to enforce their maritime borders. (Japanese, Korean, Chinese, and Taiwanese companies are all guilty as well.)

The vast majority of these illegally caught fish are ‘fenced’ through Los Palmas in the Canary Islands, owned by Spain, and through a few other ports of convenience where illegally caught fish can enter lucrative European markets.

This gets me riled up.

My home away from home in West Africa – Guinea — has the most overfished territorial waters in the world.

The U.K.’s development agency estimated that in 2009 about 110 million USD worth of stock was illegally fished off the Guinean coast.

That might not sound like much to a country such as Portugal or Japan (culprits in the overfishing), but that is serious money to a country that cannot even provide reliable power to its capital city.

The 110 million USD estimate does not even take into account the near permanent damage done to the habitat and reproductive stocks.

So why can’t the next foreign super trawler without a license in Guinean territorial waters be given a warning, then boarded, then confiscated and the crew thrown in Guinean jail until their host country groveled for their release?

Of course – there is the rub.

Guinea (and most of its neighbors) does not even have patrol boats and crews capable of executing that type of interdiction.

(Also, the last thing you want to do is give unruly Guinean soldiers the authority to start shaking down fisherman arbitrarily.)

Of course, some harbor masters, judges, and other gatekeepers in the maritime industry are probably on the take or could be easily paid off at a number of points (giving out licenses, enforcing fines, etc.)

This can also happen legally.

Even though almost all West African fisheries are now in critical condition, many licenses are sold legally for hard-to-turn-down sums.

Some ideas:

1. The U.S., France, and other bi-lateral donors should kill a few of their grossly ineffective aid programs, and spend the money on professionalizing and equipping a local coast guard interdiction team. (Just one small ship would do it.)

If the E.U. is as concerned as they say, then this should be right up their alley.

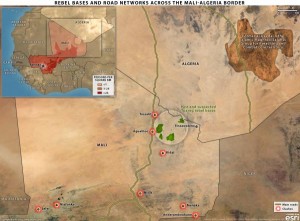

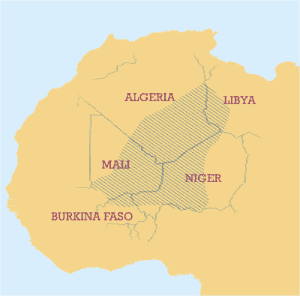

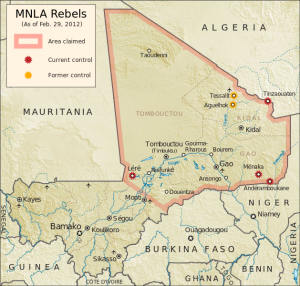

Most West African countries (excluding Mali and Mauritania and Niger perhaps) could not care less about anti-terrorism, while illegal fishing on the other hand is a hot button domestic political issue.

The local authorities will be ready, willing, and receptive to assist in kicking the bums out of their territorial waters.

*Interesting model: Australia was concerned that other Pacific countries’ lax fisheries enforcement was hurting Australian interests. So the Australian government created a training program along these lines for a number of neighboring countries that has been very successful in curbing illegal maritime activity.

This is the Sodom and Gomorrah of illegal fishing, and as long as it continues to offer a back door to E.U. markets, I refuse to believe that Spain is at all concerned with the plight of West African fisheries.

3. West African countries might enlist the help of international companies that are also concerned with maritime criminality.

The obvious partner would be the oil companies operating in their territorial waters.

The oil companies might allow host country customs officers to ride on their ships, or use their surveillance helicopters, etc.

This idea needs to be fleshed out, but it seems like a natural partnership.

I get tired of the numerous conspiracy theories that accuse Europe or the U.S. or China of commercially pillaging Africa; most of the less nuanced theories are simply critiques of capitalism.

This fishing business, however, is as clear as day: more developed countries (including some more developed African countries) are plundering poor countries’ fisheries simply because they can.

And they are doing it as fast as possible because someone else will if they don’t, and because they need to do it before these countries get their act together and start enforcing their own laws.