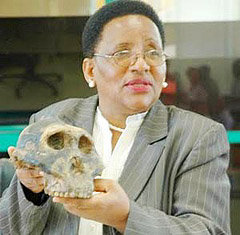

Last week Tanzanian MP, Magdalena Sakaya, publically accused Tanzania’s Minister for Tourism, Shamsa Mwangunga, of deceit with regards to her attempt to sell ivory stockpiles.

This is no small matter. Sakaya is one of a handful of outspoken backbenchers who the government of Tanzania is increasingly suppressing. Just last week, for instance, the Court of Appeals refused to allow any independent candidates in this year’s national election.

Shamsa is one of the most corrupt members of the Tanzanian government. She led the failed effort to obtain permission from the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) in Doha last March to sell a stockpile of elephant tusks.

Sakaya noted that 11 of the 27 tonnes of illegal ivory confiscated worldwide in 2007 came from Tanzania. And in 2009 that number was 12 of 24. (Elephant Trade Information System)

Yet, Sakaya explained, official records by the Ministry of Tourism or any other government department show no such large numbers of confiscated ivory.

Why not?

“Conspiracy to legalize trade of elephant tusks and their products surrounds the request,” Sakaya said in Parliament. “The Opposition camp believes the request is a ploy intended to deceive Tanzanians.”

Sakaya charged “high ranking government officials” with running a syndicate of poaching and suggested that it would be these same individuals who would have benefited from the ivory sale had CITES approved it.

Many of us are wondering, now, if Shamsa’s new push for a Serengeti road is in typical personal retribution for her failed effort to sell ivory at CITES.

In an interview with The Citizen last week, the minister denied that the 40-kilometer stretch of east-west road through the northern Serengeti would disrupt the wildebeest migration.

What?!! What planet does this person come from?

Depending upon the weather as many as a million wildebeest and half again as many zebra and other gazelle funnel north through this relatively small area into Kenya’s Maasai Mara every year.

To the east is heavily populated Kenya; to the west is heavily populated Tanzania. It’s their only route to the fresh and lasting grasses that the Mara provides during the dry season.

If the road is as heavily used as anticipated, this will result in massive disruption of the migration. Consider the extraordinary efforts that were employed by the Alaskan pipeline, including high bridges and deep tunnels, to lessen the effect on the caribou migration in a part of the planet where not another soul lives or needs to drive on a road!

Consider the massive destruction of the wildebeest migration in Botswana when the veterinary fence was built there in the 1980s.

The evidence is the stuff that a 3rd grader can use for a science report.

“Those criticizing the road construction know nothing about what we’ve planned,” Shamsa claimed.

That’s for sure. Kickbacks, new clothes from Zurich, foreign trips….

Click here to join the growing forces opposing the road.