The Mali war has reignited an old debate: should precious artifacts always be returned to the motherland, or should they be kept in safety by the greater, more stable powers of the world?

The Mali war has reignited an old debate: should precious artifacts always be returned to the motherland, or should they be kept in safety by the greater, more stable powers of the world?

Yesterday France returned to Nigeria in an elaborate ceremonial handover several confiscations of ancient Nok Arts, prized terra cotta sculptures of Nigerian empires of the 6th century. Over the last several years Yale University has begun a near complete repatriation of the Hiram Bigham artifacts the explorer took from Machu-Picchu in the early 20th century.

And while Paris remains replete with Egyptian artifacts like the obelisk acquired especially during Napoleon’s reign, France is slowly repatriating these, too.

And then comes Mali.

Without ancient artifacts from foreign lands such august institutions as the British Museum would be near meaningless. Chicago’s Field Museum would be emasculated. Taipei’s National Palace Museum would be crushed. And the Louvre – my goodness, Le Louvre, would be nothing more than a home for the Mona Lisa.

But is it right that such national treasures be housed away from the Motherland?

The treasures of Timbuktu rank right up there with the pyramids and Inca kings. In fact, many believe they are the most precious artifacts the world has.

This is because among its mosques and building relics are housed many of the world’s oldest written manuscripts. The oldest registered manuscript – at least before the current war – was dated from 1204. It included texts not just on world religion but astronomy, women’s rights, alchemy and medicine, mathematics and linguistics.

Timbuktu was a natural place for such ancient manuscripts. For several millennia before the modern age it was the crossroads of two major trade routes: the Saharan camel route with the Niger River.

But it was not until the 16th century when the area was arguably at its prime that a famous and wealthy scholar, Mohammed abu Bakr al-Wangari, established a “library” of ancient scrolls and documents. He spent the last 30 years of his life collecting these treasures, and when he died in 1594 they were inherited by his seven sons.

Collection and restoration continued for the centuries thereafter, but without a strong centralized government it was haphazard and often random. Timbuktu’s most prominent families became identified with their libraries of ancient texts.

By the turn of the 20th Century it was estimated that more than a quarter million books, notes, drawings and other relics of the past were being lovingly preserved by literally thousands of Timbuktu’s 100,000 residents.

UNESCO became deeply involved years ago, and in 2005 a huge portion of its cultural restoration budget was dedicated to Timbuktu alone.

But because the manuscripts – the most precious treasures of all – were still legally in the hands of individual families, UNESCO cleverly over the years poured its funds into the remains of ancient mosques and mausoleums. Slowly over time these attracted manuscripts.

Still the vast majority of texts were aggressively retained and often hidden by individual families. In 2005 South Africa convinced many of them to stop burying ancient parchment in the sand whenever trouble arose, and began a library.

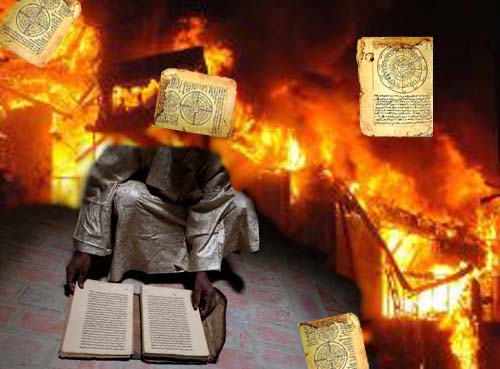

That extraordinary effort went up in flames as the Islamists left Timbuktu last week.

One of the most visible of the many libraries was Timbuktu’s Ahmed Baba Institute for Higher Studies and Islamic Research. When the Islamists first took over Timbuktu, the adroit director managed to convince one of the leaders of the importance of the texts to Islamic law.

Then, over the next months, he smuggled 28,000 of the most precious manuscripts out of the building. When the Islamists left, they burned what was left.

How much has been lost? Inventory is still going on, but the point is that most of these remarkable documents are still in private hands, libraries and collections of various Timbuktu families.

Is it time that such precious relics of humankind be removed to safer places? Or at the very least removed to Bamako and protected there?

The treasures belong in the country of their origin. They can be protected, as were the 28,000 manuscripts which were buried in a vault as planned in such an emergency. Instability can erupt quickly anywhere in the world. We are not the superior caretakers… There are intellectuals everywhere. The burning of books in WWII indicates that even those nations you deem superior protectors of other’s artifacts can slip into the hands of tyrants.

Confiscated is too strong a word – – they should be taken into safekeeping, ASAP. – Bob Chatov

Agree w Ms. Werner & Mr. Chatov (above). Artifacts require immediate protection. (Actually, I don’t care where, as long as they are carefully preserved & inventories &, when safe, returned home).

Well, friends, this is an interesting conundrum. It reminds me of how little planning our gov’t put into treasures in Bagdhad before we bombed it. Sad, sad, sad, ashes to ashes, dust o dust. (note: my master’s is in Library Science so have had such issues on my radar for many years)

This is a big conundrum: it was pushed in into prominence by the efforts to find and to restore to its original owners or their descendants art stolen by the Nazi government. Then it extended to mostly ancient artifacts coming out of Europe. A rough rule has been that items taken after World War ii have been returned whereas items taken before WWIi have not.

There have been exceptions.

The Greek authorities have been trying to get the Elgin Marbles, the inside frieze from the Parthenon back for a long time without even a budge on that direction by the British Museum which considers them British having held them safely for nearly 200 years.

The University of Chicago has a large amount of Persian artifacts, including a large number of written tablets which the government of Iran has wanted back without any progress.

Questions, among others, raised by all of this are whether the world has better access to them where they are, whether the original country can take care of them as well, and whether the original country has lost rights to the artifacts over time.

It’s all tricky. But the access question particularly as to documents is helped by the Internet where the documents can be put online for whole world to study and marvel at.