It could be in an unexpected poem, a playground of happy children, the smells of the holidays … or the crater at sunrise. This is when your testy, challenged human spirit inflates with joy despite every reason on earth it shouldn’t, and you know everything is just fine.

It could be in an unexpected poem, a playground of happy children, the smells of the holidays … or the crater at sunrise. This is when your testy, challenged human spirit inflates with joy despite every reason on earth it shouldn’t, and you know everything is just fine.

This isn’t the best time for game viewing in the crater, although few tourists who come now realize this. There’s probably fewer than 5-6,000 animals from the peak in March and April of more than 20,000.

But all that transitory wildlife is only a part of the crater’s story. The inorganic magnitude of its landscape is unmatched anywhere on earth.

Right now as the rough winds signal that rains won’t return for six months, the thick cloud cover of the season will clear for a few hours in the late morning. This morning we had one of the most crystal clear crater mornings I can remember.

It’s only 12 miles across but it seems like hundreds. You’re constantly recalibrating your depth perception. The crater’s rough edges are still lush green, still sucking the last of the fresh-water rivers sinking down from the highlands. But brown is sweeping the floor as it becomes drier and drier, producing this most marvelous contrast of color.

At first everything is pastel and then the morning explodes and there’s this quilt of primary color.

It was hard today with the wind so strong to hear all the bird song, but whenever the wind died the red-naped lark seemed to be singing from one side to the other. We saw nearly 30 crested crane honking then leaving their long necks outstretched as if still tied to the sound long gone.

When it finally warmed to 50 then 60 and finally 70 degrees, the couple thousand wilde that remained started to blart and a few began prancing around. The zebra started barking and the hippo started grunting and you knew that the ossified night of the cold season was at least for a while banished.

But only for a short while. Day time on the equator is the same twelve hours more or less year round. But the overcast of the dry season reforms by early afternoon, the strong winds that seemed to sweep away the morning chill die, and cold settles down from the thick grey cloud quite early, probably by 3 p.m., and the animals and birds slow down, stop talking.

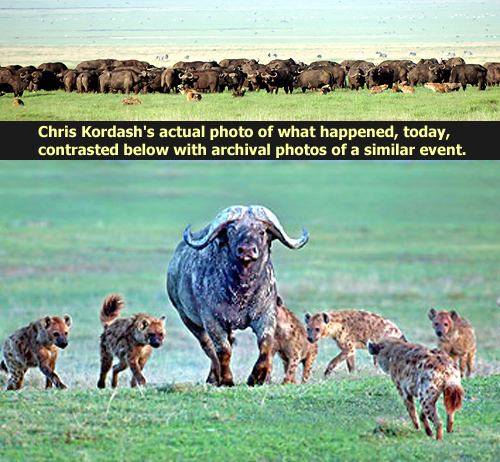

Everything in the world has to rest. The drama of the crater in March and April is sometimes overwhelming. You can’t separate the screams of the hoops of the hyaena from the screams of the elephants, and cackles of the dozens of vultures on a kill.

The movement and tension among the animals is overstimulating. No one has time to appreciate the enormous canvas painted when the world’s largest volcano self-destructed three million years ago.

Mt. Makarot never moves (you’ll have to wait to see the Shifting Sands for that!) The great forests of the acacia lehai seem undaunted even by this wind. The deep curving crevices sliding down the crater’s sides hold their form, but the grandeur of all this is missed in the mayhem of the wet season animal free-for-all.

This is the time the crater’s sleeping. That’s what it seems like, sleeping and recovering, and as our rover descended around the curves and switchbacks of the trail down it was as if we were navigating into a dream with the privileged skill of shaman. And when we climbed out during the peace of the midday and looked back, the landscape pressed into our memories like the tune you’ll never forget but will never be able to fully recreate.

The wilde have migrated out. The tens of thousands of Abdim stork and thousands of white stork and myriads of other migrants are gone. For some reason today even the eland had disappeared…

Leaving an earth so huge with the tiny little you there twisting about somewhere maybe inconsequential but you think it’s in the middle, trying to comprehend it all. Endless, right? Something forever is rare in our world, but that’s what the crater was expressing today, its implacable eternity.

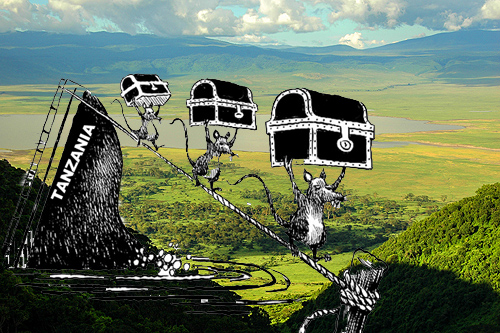

Education is fine if you’ve got something to do with it. Is there going to be war in Ngorongoro?

Education is fine if you’ve got something to do with it. Is there going to be war in Ngorongoro?