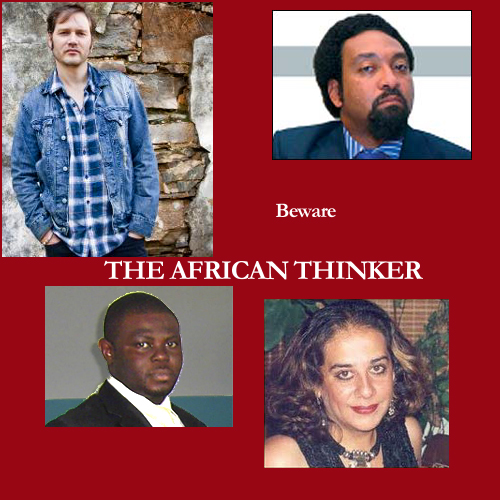

South African Richard Pithouse, Egyptian Gamal Nkrumah, Kenyan Rasna Warah, and Nigerian Rotimi FasanOccupy Wall Street is seen from Africa with a clarity we’re missing here at home. As Africa sees it, American youth’s frontal assault on unbridled capitalism is not going to end quietly.

The “unbridled” is an important distinction from the sister movement of the 1930s which gave rise to an unique version of South African communism that has continued as a political force, there, until today. Back then capitalism was going to fall lock, stock and wall safe. Not now.

South Africans, Nigerians, Egyptians and Kenyans in particular see capitalism as here to stay, but as something that needs to be hugely reigned in, and they see the OCWS as an indication it is really going to happen this time.

There have been only a few placards in Nairobi, and a greater but still smallish response in South Africa’s three main cities, but a massive amount of discussion in the media, there. I think one reason the demonstrations are smaller, is because relative unemployment has not spiked so high as it has here. The discontent relative to before is more intellectual than economic.

And African economies are much more regulated to begin with than ours.

Few Africans are in a better position to compare OCWS with the Arab Spring than Egyptian Gamal Nkrumah. The son of Africa’s first independent president (in Ghana), he married an Egyptian and has lived there permanently for a number of years. Recently Kkrumah asked about OCWS:

“Will this spontaneous outbreak of angst be hijacked and neutered or will it become, like the anger of Egyptians, the backbone of a new social contract?”

Nkrumah isn’t sure. He worries that the established financial system in America is just too hard to crack:

“The game of global finance is as dirty as hell… The international meltdown is a harsh indictment of the global financial system [but] bankers don’t seem to have a conscience and [all] the people [can do] is strike the fear of God into them.”

Nevertheless, my survey of African analysts suggests Nkrumah is in the minority. Although cautious and not suggesting our entire system is going to be revolutionized, most African analysts believe OCWS foreshadows significant change in America.

Everyone knows America with China at its heels controls the world economy. So what happens in America effects everyone, without exception. African’s interest is not simply academic. In fact what happens to the OCWS may have a more immediate effect on the everyday lives of Africans than it does on most Americans.

The very influential young thinktanker in South Africa, Richard Pithouse, has often written that the developing world has been consciously subordinated to us – the developed world – by a brute and unfair force called DEBT. Think about it. Where is most of the gold in the world? South Africa. Where is most of the oil?

But who controls the gold and the oil? Neither South Africans nor Nigerians, but Americans and Europeans.

“Debt,” Pithouse writes “became a key instrument through which the domination of the North was reasserted over the South.”

But that suffering has now come home to roost in America, according to Pithouse. The “servitude of the debtor is increasingly also the condition of [American] home-owners, students and others” who are being made to pay for the financial crisis created by their overlords, the bankers.

At last, Pithouse exclaims, OCWS in America is “a crucial realisation that for too long society has been subordinated to capital.”

“The prevailing capitalist economic system has clearly failed. It has deepened inequality between people and nations and caused much misery. Its excesses must be curbed,” writes , Kenyan analyst Rasna Warah in her article “Is the End of Global Capitalism Nigh?”

She answers her own question with a “Probably Not,” essentially what all the analysts in Africa concede. But she opines that as Africa emerges from the Arab Spring it will invent “a hybrid, more humane capitalist-cum-socialist system … where wealth will … be used to promote the greater good rather than individual and corporate interests.”

The Nigerian analyst and sometimes poet, Rotimi Fasan, compared Wall Street bankers to the worst of his own corrupt Nigerian autocrats. And like many, many writers throughout Africa he wonders if what is happening now “might be the beginning of the West’s version of … the Arab Spring.”

He refers to the west’s “crumbling economies” and cautions that “things may not take that shape immediately. But they might over time. Those who imagine that such eruptions could only happen in Africa of sit-tight leaders” do not fully understand what’s happening.

Which leads me to another dominant theme throughout all of Africa’s reflection on the protest:

Our media is minimizing the demonstrations.

“If these protests were occurring in any other part of the world, Western [media] would be describing them as an ‘American Spring’ that could topple a government,” Warah writes.

Warah and other Africans believe that the American media is part and parcel of the greater problem. “The large [American] media networks are part of the very corporate culture that the protesters are against,” Warah explains to her readers, so naturally they are minimizing the story.

Using last week’s celebrations of Martin Luther King, Pithouse claims that the famous statement that young blacks in the 1950s faced life “as a long and desolate corridor with no exit sign” applies to all American youth, today.

The South African continues: “The time when each generation could expect to live better than their parents has passed. Poverty is rushing into the suburbs. Young people live with their parents into their thirties. Most cannot afford university. Most of the rest leave it with an intolerable debt burden.”

And what does this mean about America to an educated outsider?

“The borders that surround the enclaves of global privilege are shrinking in from the nation state to surround private wealth.”

Wow. Poetic but how insightful. I think Pithouse reflects many many intellectuals from abroad, especially from developing and emerging, youthful nations. They no longer look to America for direction, but for lessons as to why things went so wrong.

“When some people are living like pigs and others have land lying fallow, it is easy enough to see what must be done,” Pithouse says. “But when some people are stuck in a desolate corridor with no exits signs and others have billions in hedge funds, derivatives and all the rest, it … is more complicated. You can’t occupy a hedge fund.”

But OCWS protestors understand that “finance capital is … the collective wealth of humanity. The money controlled by Wall Street was not generated by the unique brilliance, commitment to labour and willingness to assume risk on the part of the financial elite. It was generated by the wars in the Congo and Iraq. It comes from the mines in Johannesburg, the long labour of the men who worked those mines and the equally long labour of the women that kept the homes of the miners in the villages of the Eastern Cape. It comes from the dispossession, exploitation, work and creativity of people around the world.

“That wealth, which has been captured and made private, needs to be made public.”

Pithouse concludes and warns us directly, “When a new politics, a new willingness to resist emerges from the chrysalis of obedience, it will, blinking in the sun, confront the world with no guarantees.”

Beware the thinkers of Africa. They bear the truth of experience.

Hello, Jim.

Herman Greene (Center for Ecozoic Societies) forwarded your OWS blog. I appreciate the African “take” on what’s going on in the American and World Street.

I share, in return: click here for my blog on the same topic.

I think I am in considerable agreement with your African commentators.

All best,

Ellen LaConte