The Kisiel Family safari ended with great drama this weekend. Here’s what happened and how future safaris might also achieve such success.

The Kisiel Family safari ended with great drama this weekend. Here’s what happened and how future safaris might also achieve such success.

The sheer numbers were impressive: 90-95 lions (we had some controversy regarding counting cubs), 4 leopard, 4 cheetah, African Wild Cat (somewhat unusual); thousands of elephant; dozens of thousands of gazelle and antelope; hundreds of giraffe; and possibly more than a hundred thousand wildebeest and zebra.

And there were five or six specifically dramatic events that really made the trip stand out. Why?

I’m afraid the most important answer may be a very simple one: the Kisiel’s arranged a safari that was a third longer than the average. They were on safari for 13 days and nights. The mean today is just around ten days.

That small additional time, in my estimation, is worth far more than it seems. It relieves the pressure on our planning and means that optimizing opportunities is much easier.

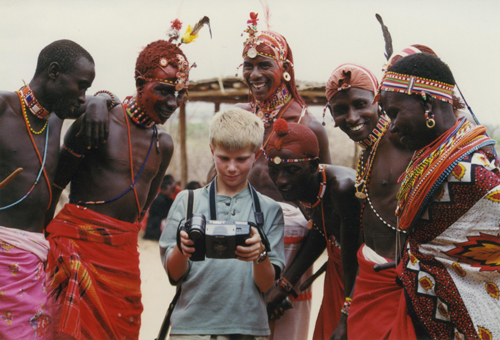

Enthusiasm. You’ve got to have enthusiasm to do a safari right, and the Kisiel’s did! Every time I offered a long day or a short day, they chose a long day. Quite simply, this like the length of the overall safari increases our opportunities.

Almost as important was global warming, and that of course, will continue. In the tropics in Africa global warming means far more severe weather, and that means when it rains it rains more. Tanzania’s northern safari circuit is a rainy circuit and so in an ironic way, it benefits from global warming.

(It’s also suffering. Flooding is taking a serious toll: see my blog last year about the destruction of Lake Manyara’s national park entrance.)

Finally, there’s luck. Yes, it’s true to some degree that you make your own luck, and I guess the Kisiel’s are masters!

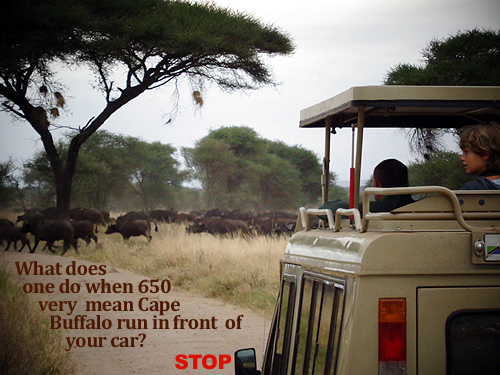

STAMPEDING BUF

At least 650 literally stampeding African Buffalo stopped our attempted quick exit from Tarangire National Park as they stormed in front of us just before the main road bridge around 9 a.m. one morning.

Buffalo numbers are hard to come by since conservation organizations grew disinterested as their populations increased throughout the last quarter century. But in the last five years or so, populations have stabilized or declined and led to some troubling research about viruses and other diseases the African Buffalo seems to be spreading.

At the beginning of the noticeable decline, lion researcher Craig Packard identified a virus that was weakening if not killing many buffalo (which subsequently led to lions dying that were taking advantage of the weakened population and succombing to the same virus).

Packard’s study inspired other research and more recent findings by the National Institute’s of Health and veterinarian scientists at the University of Pretoria have documented both viral and bacterial infections that seem to be spreading continent-wide among the Buf.

Large groups of buffalo are common because they are a close herding animal. But we have come to presume a large group is around a hundred, and this was six or seven times larger.

In addition to just the great drama of seeing this it motivates us to return to current research to try to determine if this was simply a very rare anomaly or something more meaningful.

FLAMINGO FLYING CARPET

East Africa has both the greater and lesser flamingo, the latter being more pink but considerably smaller. Throughout the continent the lesser flamingo is considered “near-threatened” because of habitat degradation and erosion. (The greater flamingo has a much larger range and considerably greater numbers and is still considered healthy.)

I recall in the 1970s a number of East Africa lakes were completely saturated with lesser flamingoes: Nakuru, Baringo, Elementaita, Bogoria and Manyara in particular.

If you’ve seen the 1985 movie Out of Africa and sat through the credits at the end of the film, you’ll see an unending stream of flamingoes overflown by the camera aircraft.

But flamingo are very sensitive to the alkalinity of the water they require. Their entire food source is a small shrimp that feeds on a certain type of algae. Too much rain or drainage of their lakes alters this sensitive dynamic. Global warming and agricultural development have noticeably impacted what we’ve seen on safari lately.

Until this trip! We pulled into the south end of Lake Manyara and witnessed one of the greatest collections of flamingos I can remember since the late 1970s. At one point a mass too large for me to estimate took off coloring nearly our entire field of vision.

This end of Lake Manyara has undergone a radical agricultural transformation in the last ten years that has led to an explosion of rice and sugar cane farming. Because it has so positively transformed the communities here, it was hard to criticize. Has global warming actually balanced out this dynamic, at least in Lake Manyara?

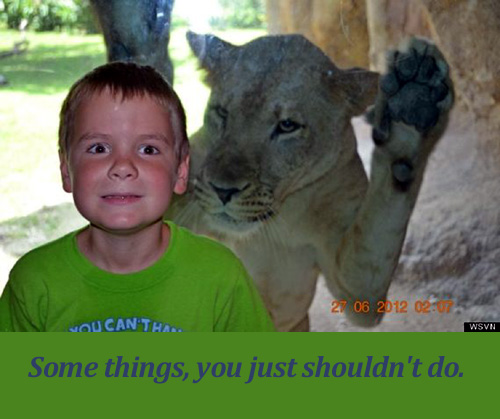

CHEETAH ON CAR

If global warming and the resultant more rain in the highlands is helping Manyara, it may be harming parts of the Serengeti.

Global warming isn’t just more rain as the ice caps melt. It’s also more severe droughts. Really, it’s better to recognize global warming as making weather more severe, rain and drought. And that’s what happened to us in the Serengeti. It was particularly disappointing for me when a completely unusual dust storm in the southeast Serengeti prevented us from visiting the area.

But the karma was with us, and the extra time we had to game drive in the park’s southwest led to a young male cheetah jumping on our car. In the car was Camden Reiss and it was his birthday!

It’s not unusual for cheetah, mostly male, to do this. They want a better view and I believe are among the most inquisitive of the big cats.

THE MIGRATION

Everyone wants to see the migration, of course, and the amount of disinformation in the media and travel industry constantly dumbfounds me.

I’ve written so much about this, rather than link you to a dozen previous blogs simply click the Index tab to the right for the list of posts. Historically at this time of the year the migration would mostly be in Kenya, and in fact Kenyan lodges and hoteliers reported a mass arrival very early this year, in late May.

But when we arrived the central Serengeti about a week ago, bingo!

Now it’s very hard for any first-time visitor to judge if they’ve really seen the migration or not. Even those of us guides with decades of experience struggle with estimating large scenes of animals.

I figured we saw about 20,000 animals, and that was plenty enough to fill the plains in our view. Steve Taylor, guiding for EWT at the same time, reported the same situation when he was in Seronera a couple days before us.

Why? That was simple. There had been unusual rains and the grass was green. Wilde do not hard-wire migrate like birds. They move where there’s food, and there was plenty in and around Seronera.

But it wasn’t over when we moved north! On our last day we saw considerably more wilde and witnessed crocs pulling down two wildebeest from a daring and dramatic file of animals trying to cross the Mara River.

Excitement unbelievable, but for me, confusion, too. Were the Kenyans bluffing?

No. I spoke subsequently to both tourists and hoteliers and I believe the Kenyans, and I believe that the great majority of the migration is in Kenya’s Mara right now.

But the rains have been extraordinary and the population is healthy, and right now a large and visible part of the migration is strung all the way from northern Tanzania back to Seronera in the center of the park. It probably won’t stay much longer, as the rains do seem to be subsiding in the south. But I won’t be surprised if next year’s Frankfurt Zoological Society estimate of the population breaks records.

LION SOCIOLOGY LESSON

On that same day that we saw the river crossing, we also witnessed what to me may be the highlight of the trip. I wouldn’t expect my clients to embrace this conclusion, but this was a very rare and important experience.

We watched first-hand a mother lioness trying to kick out one of her sons from the pride. It’s a long understood part of lion sociology and biology that the mother has to do this before the son gets bigger than she is. Full grown male lions are 50% larger than females.

And there are plenty of documented videos to show it. But I had never personally witnessed it in the wild.

It’s always difficult to predict anything in the wild. But with sufficient time and patience, together with careful planning, most safaris can achieve the wonder and drama that the Kisiel family enjoyed!

Safari Njema!