Bumpy road, alkaline dust, wind in your face. And a honey badger, some impala, hartebeest, elephant, a serval in a tree killed by a leopard and a family of 11 lion taking down a bull buffalo.

Bumpy road, alkaline dust, wind in your face. And a honey badger, some impala, hartebeest, elephant, a serval in a tree killed by a leopard and a family of 11 lion taking down a bull buffalo.

Anyone who only reads first paragraphs might be misled.

It was hardly an ordinary start. We lucked out big time. Sue MacDonald kept saying “I don’t believe; can you believe it?” And as is often the case with great game drives, it was basically luck and not strategy that took us to this extraordinary beginning.

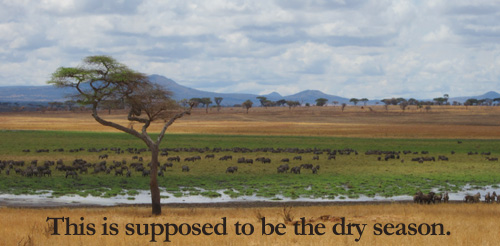

Following the first couple days in Nairobi for our normal political and cultural touring and to shake as much jetlag as possible into the congested throngs of people we walked through on the street, we flew into the southwest Serengeti, to Ndutu Lodge. Yesterday there were two others besides our group, and today we’re alone. This is because of the common knowledge that the migration which is centered here in March and April is long gone.

But what so many television special driven tourists don’t reflect on is that animals and wilderness does not follow a TV schedule. It goes on year-round. Sure there will be times that will basically provide more animals than others, but there are very special things that happen at all the different times of the year.

I’ve written before about the discovery of the buffalo virus that was leading to more lion kills and lion deaths, but even so lion killing a buffalo is no easy task. I don’t think a lion even considers taking down a buf unless more customary food like zebra and wildebeest aren’t available. It would be like going to Whole Foods for a last-minute Friday snack and buying a complete Angus.

And that’s the case at Ndutu in the middle of the dry season. (By the way, we arrived in a rain storm, and it’s rainy today as well, but that’s really unusual. And the area essentially remains very dry.) So for the lion of Ndutu, dinner is always a challenge.

We’d heard in the middle of the night the anxious lion roars and hyanea yelps. We’d hardly been out for a few minutes past daylight when Dixon spotted a lone female walking fast on the top of a ridge about 500 yards away.

We drove up to her and I immediately noticed that she was limping, and that her belly was terribly contracted, a sign she hadn’t eaten for days. Clearly last night she was involved in a failed hunt of something that injured her right shoulder.

She took no notice of us and kept on her mission driven limped walk. She hesitated only momentarily to call and then listened as another lion called back from the far distance. She started to walk again.

Then all of a sudden out of some low bushes runs a subadult male covered in blood. The female we had been following laid her ears close to her head, turned tale and began running with the bloody faced male in close pursuit.

She was obviously not a part of the pride that currently owned this territory, but rather than following her we wanted to figure out the bloody face of the pursuer.

Soon we found other lion, three mature females and five cubs of various ages, all bloodied but clustered together as if something was attacking them.

Then we saw literally ten feet from our car in the bush a giant male buffalo.

He was obviously dying. The giant, awesome beast lifted his head back towards me and I saw that distinctive glaze in the eyes of a dying animal. Animals have expressions just like us, just not in the face.

Every time a lion got near him he’d stand up and begin to swing his deadly horns.

The older lion knew to stay well away, but the younger kids couldn’t suppress their hunger. They would move towards him, even jump on him, and he’d growl and swing his head. The youngest cub, about 4½ months old, got a seething cash on his little neck.

So we watched this for some time as the buffalo seemed to be on his last breath, and then when he seemed to stop breathing, a lion would close in, and he would stumble to his feet swinging his head, braying.

Finally, still alive, he lost all strength and the family knew it. They were on him at once: the kids on the back, the larger lion digging into the soft flesh areas. We left before he was dead.

A few hours later, on our way back to the lodge, we stopped to review the situation, and the buf was dead. In just that short several hours the lion had carved an enormous amount from the available meat and most were too full to eat another bite. But the male was close on the kill, as they always are, reluctant to give way so long as a single morsel of meat is left.

Even though he was too full to eat it.

Then came our second wonder. Two elephant were strolling down the lake shore which was about 50 yards away. But the wind was directly on them, off the kill, and immediately the mother ele started scenting the air.

Before long she was charging the lion, chasing them away and trumpeting loudly. The lion dutifully stood clear, the male the last to do so, and she kept up the harassment until for some reason she felt appropriately vindicated, and went off.

No. It was not an ordinary start to a safari. But on the other hand it wasn’t totally unusual. This is the most stressful time for Ndutu. Except for the aberrant rains that came with us, the veld is parched, a powdery salt blown almost like smog into the mostly still veld by the dawn and dusk breezes. Unlike March when I’m here, there is only a fraction of the normal bird song, a thin sliver of the number of animals always here then.

But predators don’t migrate. If they’re to survive, this is when they have to show their stuff. And for the lucky visitor, like us, a once-in-a-lifetime scene unfolds into our own alien world.