It was sad, but inevitable. Big Mane’s body was already headed away from the tree that cloaked his sleeping brother with shade when he stopped unexpectedly, twisted his huge head and mane and looked back at his brother. He stared for what seemed like a very long time before finally turning his head into the fierce Serengeti winds and walked away.

It was sad, but inevitable. Big Mane’s body was already headed away from the tree that cloaked his sleeping brother with shade when he stopped unexpectedly, twisted his huge head and mane and looked back at his brother. He stared for what seemed like a very long time before finally turning his head into the fierce Serengeti winds and walked away.

The two brothers had lived together ever since their mother kicked them out in a horrible battle down by the Wandu Swamp where they were born. Big Mane had tried to join a hunt that Mom and sissy were just beginning. The big female lioness attacked her son, stripping her claw across his chest. Big Mane jumped back so confused he felt nothing. But then when Mom hissed at him we snarled back and began to attack her. But he just wasn’t big enough yet. She would have killed them.

Bro had sat the fight out, but when Big Mane went running his Mom began to chase him, too.

The two boys were essentially twins, but one was robust and strong and the other much less so. Big Mane had streaks of black in his enormous puffed hairdo when he was hardly two years old. At four his mane was almost complete. In the strong eastern winds of the Serengeti at the end of the dry season he looked like a Greek God ready to strike.

Bro’s black streaks took a year longer to appear, and while also a full mane now it was often twisted up by the flies that he couldn’t be bothered to paw away and gnarled up by the prickly seeds of the hibiscus that he often walked through incautiously.

Big Mane did the killing. Bro tried to help and sometimes really did, like the time he clamped straight into the aorta of the sick buffalo while Big Mane was still clamped onto the hinds. But that was the exception. Almost always Big Mane was the striker and the closer, and with a much greater success ratio than the 1:5 suffered by most healthy lions.

Even so Bro suffered a lot more than Big Mane. When called into action however rarely, he usually was too hesitant. The wilde’s horn cut a huge slash under his right eye, so deep that when it healed the scar tissue cluttered the vision of that eye. That was about a year ago, just before the last rains began when he was so worried that as the veld greened up and the animals grew strong and less easy for Big Mane to get, that his brother might leave him altogether.

The wet season is hard for lion. Their heyday is now, when the earth looks miserable, the dust grows into monstrous whirling dervishes and dances like a laughing devil over the plains. That’s when the animals are easy for Big Mane to get.

The two brothers were resting in the shade behind a big rock beside an ephemeral pool of water when we first came upon them. The pool was drying up so quickly its edges were white with salt. Big Mane rested calmly, his head up and giant mane blowing in the wind but his eyes closed as he slept off the last of his huge belly, his last kill.

He hadn’t been proud of it. My clients couldn’t understand why the line of 40 or so zebra were hardly 50 meters away from them, stomping their feet and snorting, taunting the beasts. But they knew the brothers’ bellies were full. They needed to drink. Big Mane knew they needed to drink. It was a simple waiting game until his belly was small, again.

For the last few weeks Bro was getting anxious, again. He couldn’t control his hunger like Big Mane could. So Bro started to mess up Big Mane’s kill attempts. He raised his body before Big Mane made the jump. He sneezed when the dust blew into his bad eye. And his left hind leg was getting so weak, now, that the few times he tried to join the chase he tripped, and Big Mane instinctively aborted the hunt with an increasingly annoying worry he couldn’t quite understand.

Big Mane’s belly was big, Bro’s less so, but neither as big as it would have been with zebra. We drove over to where the vultures and jackals were cleaning up their last feast, only it wasn’t really theirs. It was a Grant’s gazelle, usually too little, too swift and to dangerous with its pointy horns for lion. Obviously a cheetah had taken it down, and obviously Big Mane had just walked over and politely given the cheetah a few seconds to get away before it became the second course.

So Bro got his meal, too. But of late Big Mane wasn’t sharing like he used to. The rains were coming. There had been a sprinkle the night before. A faint patina of green covered the desiccated veld. Things wouldn’t be as easy, anymore. Big Mane had to beef up. It could be a week between successful take-downs once the pools filled and the grasslands turned a beautiful green. He’d have to get zebra, now, not just the spoils of a little cheetah.

A massive gust of wind turned the whole plains into a dust storm, and the sound was furious. We quickly rolled up the windows of the car, which shook and rattled until it subsided. The veld slowly cleared. The cackling of the Egyptian geese and squealing of the superb starling penetrated the diminishing wind.

Big Mane was up. He walked ten feet to the edge of the pool and sipped some water then lowered on his haunches.

Bro was reluctant. Why leave the shade of the rock? The edge of the lake was probably a 100F. But he followed his brother. He didn’t sip any water. His stomach didn’t feel good.

Bro noticed a lone acacia tree off about a 100 meters. He began lumbering to it, slowly, harshly, puffs of dust brushing his sides with every footstep. Big Mane opened his eyes and turned his head to watch his brother lumber to the tree.

It took Bro forever to get to the tree, his left back foot leaving drag marks on the desiccated earth like a snake’s trail. He got there and flopped over on his side.

Big Mane stared at him for a long while remembering the great battle and Wandu Swamp, the buf takedown but then the more recent memories of failed hunts replaced older memories with anger.

He licked his chops. Gazelle was pitifully untasteful. He got up, waited a moment but Bro didn’t stir in the distance, so he turned in the other direction and walked away into the open veld scattering zebra and gazelle all over the place.

Nanyukie, Eastern Serengeti

Tired but infuriated I watched the House Havoc to its end. Then just as my brain sensed a wee bit of insight a client sent me the Times’ article castigating tourists who drive too close to cheetah.

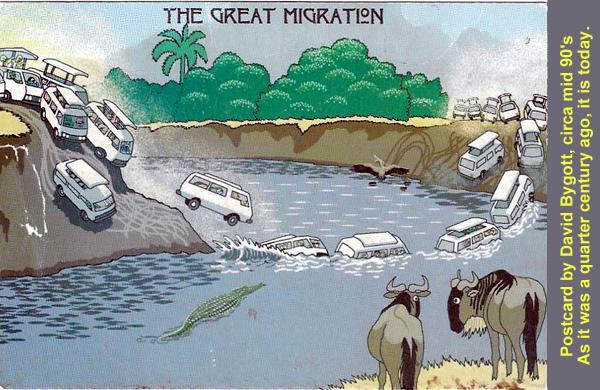

Tired but infuriated I watched the House Havoc to its end. Then just as my brain sensed a wee bit of insight a client sent me the Times’ article castigating tourists who drive too close to cheetah. I don’t like crowds… of people, that is. I take my rovers into tens of thousands of wildebeest, sometimes hundreds of thousands. My cars are often the only ones in view.

I don’t like crowds… of people, that is. I take my rovers into tens of thousands of wildebeest, sometimes hundreds of thousands. My cars are often the only ones in view. The “unlawful and

The “unlawful and  Many still considered him a youngster. Only 6-7 feet long he was little compared to the monsters of Lake Turkana, many photographed at over 25 feet. But he didn’t feel young, anymore.

Many still considered him a youngster. Only 6-7 feet long he was little compared to the monsters of Lake Turkana, many photographed at over 25 feet. But he didn’t feel young, anymore. We left Ndutu after seeing another cheetah with three cubs, not sure exactly how we would go. Our destination was a lovely camp on the north end of the crater but the way you would go depends upon the dust.

We left Ndutu after seeing another cheetah with three cubs, not sure exactly how we would go. Our destination was a lovely camp on the north end of the crater but the way you would go depends upon the dust. It was sad, but inevitable. Big Mane’s body was already headed away from the tree that cloaked his sleeping brother with shade when he stopped unexpectedly, twisted his huge head and mane and looked back at his brother. He stared for what seemed like a very long time before finally turning his head into the fierce Serengeti winds and walked away.

It was sad, but inevitable. Big Mane’s body was already headed away from the tree that cloaked his sleeping brother with shade when he stopped unexpectedly, twisted his huge head and mane and looked back at his brother. He stared for what seemed like a very long time before finally turning his head into the fierce Serengeti winds and walked away. I’m often asked but I have no favorite animal. The Serengeti doesn’t attract me because of magnificent lions or angry elephant or dainty dik-dik. No single tree or bug or animal has any attraction at all except when you think of them all together. So all together is the most wondrous, my favorite, place in the world, the Serengeti.

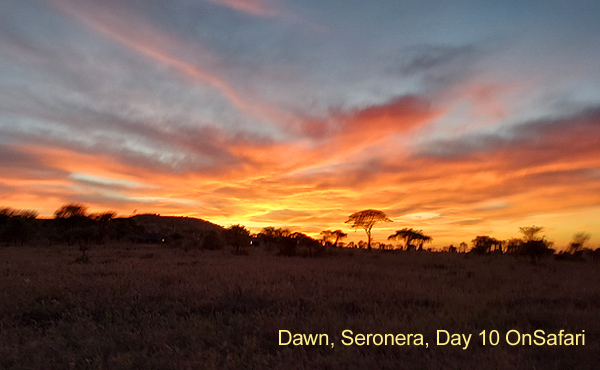

I’m often asked but I have no favorite animal. The Serengeti doesn’t attract me because of magnificent lions or angry elephant or dainty dik-dik. No single tree or bug or animal has any attraction at all except when you think of them all together. So all together is the most wondrous, my favorite, place in the world, the Serengeti. The temperature in my tent as I woke at 5 a.m. was 62F and it would undoubtedly go down a few more degrees until just after 9 a.m. Dawn over the Serengeti doesn’t bring immediate warmth with its brilliant light. It rained last night and the evaporation into the still dry air actually cools things down a bit more.

The temperature in my tent as I woke at 5 a.m. was 62F and it would undoubtedly go down a few more degrees until just after 9 a.m. Dawn over the Serengeti doesn’t bring immediate warmth with its brilliant light. It rained last night and the evaporation into the still dry air actually cools things down a bit more. Those damned kids! They ruined dinner once again!

Those damned kids! They ruined dinner once again! How times have changed! I love cliches. And the pandemic has helped refresh traditions and with that, nostalgia, and with, sentimentality and so now I’m terrified. In a few weeks I head back to my most loved Serengeti. What will it be like?

How times have changed! I love cliches. And the pandemic has helped refresh traditions and with that, nostalgia, and with, sentimentality and so now I’m terrified. In a few weeks I head back to my most loved Serengeti. What will it be like? Yes, I’ve found a connection between the Serengeti and right-wing propaganda. Didn’t expect it would be so easy, but the take-home is that somebody out there – governments or dictators or god incarnate – needs to control social media. The wild west of information dissemination is destroying truth and I worry it may never be restored.

Yes, I’ve found a connection between the Serengeti and right-wing propaganda. Didn’t expect it would be so easy, but the take-home is that somebody out there – governments or dictators or god incarnate – needs to control social media. The wild west of information dissemination is destroying truth and I worry it may never be restored. You can’t travel for a year.

You can’t travel for a year. I have to constantly remind myself how wonderful – especially for first-timers – the dry season seems. To me it’s worse than the worst ever winter in Chicago; it’s earth challenging its own creation. What I see through the billows of dust are all the battles being lost to survive.

I have to constantly remind myself how wonderful – especially for first-timers – the dry season seems. To me it’s worse than the worst ever winter in Chicago; it’s earth challenging its own creation. What I see through the billows of dust are all the battles being lost to survive. Shelly’s pride is one of the most famously studied groups of lions in the Serengeti, probably the most photographed by professionals and tourists alike, and without doubt the most tame.

Shelly’s pride is one of the most famously studied groups of lions in the Serengeti, probably the most photographed by professionals and tourists alike, and without doubt the most tame. I was very worried. To begin with I don’t particularly like the dry season. The enormous amounts of dust kicked up by the rovers when traveling is constantly irritating, but more generally I just don’t like seeing the beautiful veld so dry and stressed.

I was very worried. To begin with I don’t particularly like the dry season. The enormous amounts of dust kicked up by the rovers when traveling is constantly irritating, but more generally I just don’t like seeing the beautiful veld so dry and stressed.