We were among 30 cars on one side of the Mara river – there were another 30 on the opposite side.

We were among 30 cars on one side of the Mara river – there were another 30 on the opposite side.

I don’t like crowds in the wilderness, and I avoid them pretty successfully. But this is an exception. If you want to see one of the most dramatic still truly wild components of the world’s last great animal migration, you’re going to be part of a crowd.

True, there are plenty of river crossings on the great migration route that don’t draw crowds, and I’ve enjoyed them. But the classic and most dramatic crossings are in the Mara, and there are only a couple dozen favorite crossing spots.

Unlike so many animals, wildebeest are very finicky eaters. All they will consumer is grass. Grass comes after rain. The wilde’s instinct forces them to “follow the rains,” which generally recede over the course of the year in a northwesterly direction onto Lake Victoria.

Before reaching the Mara, the great herds have crossed at least two and sometimes four or five other great rivers as they move north.

The Mara is the last and furthest northern river before the herds are turned back by developed farm fields, towns and villages. Here they cluster and start moving backwards and forwards across the river seemingly without purpose. The instinct to move is too great, and if the movement is a rebound, so be it.

This has been the case for at least the last half century. Before that they may have continued all the way to the Lake before turning around. The boundary is not natural in the wild sense, of course, and it results in the mass confusion, exceptional drama and photogenic scenes that have become the trademark of the great migration.

A bit further south the herds’ decisions to move back and forth across rivers is governed much more by actual rain. Particularly now with climate change, the intense micro-climates may mean a healthy rainfall a few miles to the north, or a drought, a few miles to the south.

I’ve often watched the herds move north out of Tanzania to Kenya right on schedule in June, but then return months early in August because of early, heavy rains in northern Tanzania.

Keep in mind that a wildlife documentary is simply an edited version of what the Miller Family saw this morning in person. I remember encountering a BBC/Nova film crew once shooting a river crossing here in the Mara, and there were at least 20 vehicles just in their team.

We were watching a newborn zebra being defended by its mom against a hyaena when we spotted massive clouds of dust several miles away above the river.

Our camp driver, of course, knew exactly what “favorite crossing place” was near the dust and we headed for it posthaste. Wilde will jump 20 feet into the river and then try (usually unsuccessfully) to scale the other side of a 20-foot canyon, but they prefer easier entries and exits, often dry river washes merging with the great Mara. There aren’t many, and everyone knows them.

To reach this crossing place, we had to drive through the herds, and that in itself was fabulous. I estimated between 3500-4500 in this particular group. They were racing in multiple files and converging on a plateau just above the crossing point.

We slowed down among their incessant blarting mixed with the anxious barking of the zebra. Clearly this group was getting psyched up to cross!

By the time we got to the crossing point most of the prime spaces were already taken by other cars. But our driver knew the river so well that we went down river all of a few hundred meters where it turned and found a beautiful viewing area right there.

Across the river were four giant crocs, pulled out onto the sun with bellies already bulging with previous crossings.

So then, like everyone, else, we just waited.

After about an hour, all of a sudden, we were surrounded by wilde! They came so fast the dust came after them! This wasn’t the crossing place, this was our secret viewing area, and it was very rocky and steep at the river’s edge.

Then almost as quickly, they moved away back into the riverine forest. For some reason, they weren’t going down the “favorite crossing place.”

After about another half hour some cars began to leave. We thought we would, too, but just as the engine turned on we could see upriver that the first of the group had reached the river’s edge at the end of the wash.

At first they didn’t seem to do anything but grow in numbers and drink the water. After about five minutes, though, the pressure of the racing wilde behind them forced them to start the swim across.

They walked until the depth of the river forced them to swim, and wilde do this by successive leaping. Water was splashing all of the place. I watched a croc leap out and grab the side of one wilde. It was soon mayhem. Six or seven abreast were swimming across, many getting drowned by others behind them, some actually swimming back across the river!

A half hour later it was all over. A very small group of about 25 wilde for some reason remained on the wash and didn’t cross, but the bulk had move onto the other side and were congregating on the plains and starting to graze.

We found a nice place much further down the river to set up our wonderful breakfast, but the river runs fast here, and numerous “floaters” or dead wildebeest passed by us.

The great migration is like one little muscle in Mother Earth. It’s a reflection of the ecological heritage that makes our planet so awesome. Until we free ourselves completely of our biological roots, we need to truly experience the power of our organic world so that we can concede that we’re only one piece in an infinite universe of life, beholden to the great migration as the wildebeest are to the rains.

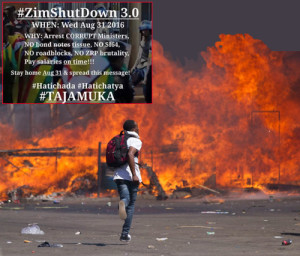

Demonstrations in Zimbabwe are increasing and the firestorm is building for tomorrow’s nationwide shutdown.

Demonstrations in Zimbabwe are increasing and the firestorm is building for tomorrow’s nationwide shutdown.