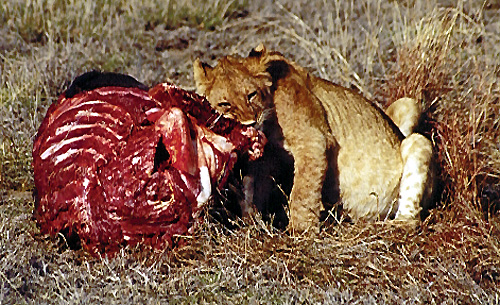

It was just after 7 a.m. and I spotted four lions devouring a wildebeest.

It was just after 7 a.m. and I spotted four lions devouring a wildebeest.

They had obviously just killed it and their faces, necks and front paws and legs were covered with blood and they were eating madly, eating like a cheetah in fact.

Lions don’t go to finishing school, and despite Mary Disse’s wonder if they ever share, they are pretty much gluttons with poor manners. But it’s really only the cheetah that eats as if the world is going to end, because it has such trouble keeping its kill.

Lions are the king of beasts, right?

There were two adult females and two 6-month old juveniles on the kill and they were absolutely frantic, and soon we learned why.

The hyaena were coming in droves.

Whether they anticipated this, or whether the new crater ecology caused by global warming has turned the tables on the king of the beasts, it was now clear why they were eating “like cheetahs.”

The first group of around a dozen cheetah arrived with the tails up, hooting and prancing around in obvious challenge to the small pride on the wildebeest kill. At first the pride took no notice.

When there were 15 hyaena the lions started to get visibly nervous, interrupting their chow-down with raised heads and barred teeth trying to dissuade the hyaena that were coming closer and closer.

At one point everyone was confused as most of the pack of hyaena turned around and chased three new hyaena that were coming towards the kill. That didn’t last long, though, and soon the three that were challenged had joined “the pack.”

There were now more than 20 hyaena and plenty for the attack.

They moved like in thrusts together, all towards the kill. Finally one of the females was bitten on her left hind leg and yelped, and at that point I expected the hyaena to tear apart the lions.

I’d seen it before.

But this time the hyaenas were more hungry than vicious. The lion stood up as if unmolested and walked away from their only partially eaten kill..

The now 25 hyaena pounced on the kill and probably one another, tearing apart every morsel that was left. By the time the lion had walked within 50m of us, found a small rise in the ground and flopped down to lick one another, the kill was practically gone.

I figured the lion had killed the wilde about 20 minutes before we arrived. We were there about an hour, and so in less than 90 minutes a wilde had been killed, eaten and totally consumed.

This is the dry season … I guess. As I’m writing this now, about 5 hours after the event, it’s raining! Reports are that the great wildebeest migration which follows the rains and should be far distant in the Mara in Kenya is fractured and partially still in the Serengeti.

This is climate change. We saw far more wildebeest and zebra in the crater than should be at this time of the year, and they must have grass. Grass only grows when it rains. It’s probably raining in Kenya’s Mara as natural, but it’s also raining here.

Yesterday in the crater we saw a pride of 23 lion near one of the hippo pools. This isn’t normal, either. Certainly there are cases I remember of large prides, but never 23. This absolutely represents a coalition of prides.

I can’t explain it other than to defer to the obvious that things are changing on the veld, and they are changing because the weather is changing. Global warming means more rain for the equatorial regions of the world (and also shorter but deeper droughts in between the heavy rains).

For my clients it was an exceptional morning. After we watched the first kill, we happened upon some juvenile males waiting in ambush for an arriving group of grazing wilde.

As usual, the juvenile males botched the attempt, although it wasn’t completely their fault. By the time the wilde had wandered anywhere near close enough to their ambush spot, there were nearly 20 cars with excited people talking far too loudly.

This is the high season. It’s when there are the most cars in the crater. But because we planned well, and got down onto the floor just after dawn long before most of the cars did, we had a dramatic and splendid morning.

Stay tuned. We’re headed into the far north Serengeti!