What does an African country do when Bill Gates says eat it or starve?

What does an African country do when Bill Gates says eat it or starve?

Most Americans think that the growing concern over what foods are safe is something that only their privileged, developed world has to suffer, that it is somewhat esoteric and – provided, of course that you aren’t culinarily involved – restricted to … nuts. (Peanuts, that is.)

Well, it’s not. In fact the debate over GMO is reaching a crescendo in Africa where scientists, multinationals, governments and NGOs like the Gates Foundation are in a diabolical battle over GM corn.

It is, literally, a matter of life and death.

Mom might wipe her brow when planning a contemporary Thanksgiving dinner at home, today. She might have to source out a natural turkey farmer and find a grocery store that sells gluten-free pie crust. This is all a lot more work than Aunt Evelyn did when the centerpiece of our holiday dinner was a jello salad.

But in Africa the sweat is over whether some people will starve or not, and my take is that GM foods are not the answer. Bill Gates disagrees.

You’ll have to be patient if using the links I’ve incorporated, because everyone is being quite deceptive. No one wants you to hear them shouting. But the uproar is rising and it’s focusing on a single of many ongoing battles:

Monsanto is one of a couple multinationals that is profiting from the development and patenting of GM crop seed, particularly corn (“maize” as it’s called elsewhere). That story is in itself distressing, as farmers who use GM seed can no longer use their own crop seed. They must buy it year after year from Monsanto.

There are literally tens of thousands, perhaps now hundreds of thousands of GM plants and organisms, and Monsanto owns a hunk of them.

One version of maize for which Monsanto had its highest hopes, MON810, whose appropriate brand name of “YieldGard” is all but ignored in the current debate, is the center of the controversy.

MON810 yields a corn that is remarkably drought resistant. It’s widely used in the U.S. and understandably was imagined as drought-plagued Africa’s savior seed.

About a third of Europe’s countries ban MON810. The most recent science from Norway declared MON810 harmful to humans, pigs, mice and butterflies.

An important European Commission (EFSA) that approves or disapproves GM products was given the task of deciding for all of Europe if Norway’s science was valid. On what many argue was a technical fault, the commission approved MON810.

The EFSA decision allowed multinational agribusiness to sue countries like Norway, France, Germany and Poland to reverse these bans, and Monsanto is succeeding in doing so… sort of.

Europe’s political interface is not yet complete, and so recently France “rebanned” MON810 after “reallowing” it. Other nations are likely to follow suit.

I can’t possibly pass judgment on the science. I can’t even figure out how to decide which science is worth reading; it’s all over the place.

The main crusader against GM foods is Prof. Gilles-Eric Séralini whose arguments verge on the hysterical. But his science is widely used by opponents of MON810.

There are many very respected groups whose approach is more measured but forceful, like the “Occupy Monsanto” crowd.

The problem – and it becomes critical in Africa – is who to believe: crusading scientists, respectable citizen groups or government commissions. No one questions that MON810 produces a much higher yield. Africa really needs a lot of corn, fast.

But I take my lead from South Africa, the most rational and developed of African countries.

Shortly after MON810 came to market about 15 years ago, the South Africans banned it. But that didn’t last long, and many anti-GMO activists in South Africa claim their government’s reversal was as a result of U.S. trade pressure.

During its use in the last decade, South African farmers recognized a need for increased pesticides and fertilizers to keep the crop going. Yes, it needed less water and from a business standpoint with the yields it was producing, it was still a good business decision.

Activists argued that the reason MON810 requires more pesticide and fertilizer is because it produces super insects and bacteria.

Late this summer, MON810 created corn was withdrawn from the South African market. It was a combination of public outcry and government regulation.

Moreover, pressured by the South African government, Monsanto agreed to compensate farmers for their unusual pesticide and fertilizer costs needed to bring MON810 corn to harvest.

It’s not clear whether this ban will be sustained nor if alternative Monsanto GM seeds will not just be used, instead. But what is clear is that the leading African country has decided MON810 is bad.

So what now?

Immediately the battle shifted north to less developed countries like Tanzania and Kenya where the seed is still allowed. But it was anything but certain Monsanto would prevail there, either.

In steps charitable giving.

Monsanto, in its ever creative marketing plans, decides to give the Bill Gates foundation free use of MON810.

And it’s an NGO coup for a foundation deeply involved in helping Africa. The cost of MON810 could be absorbed by South Africans, not by Kenyans. Now, Kenyans get it for … free.

And true to form, Kenya is now in the midst of another Shakespearean government scandal in which a quasi government agency banned MON810 before the Gates Foundation announcement, then summarily reversed itself after the announcement and, of course … nobody can say why.

Of course Monsanto dare not publicize its generosity too directly, so it’s being done through a partnership program created by an African foundation that gets most of its money from Gates.

That’s sufficient enough distance to keep Gates out of the maelstrom.

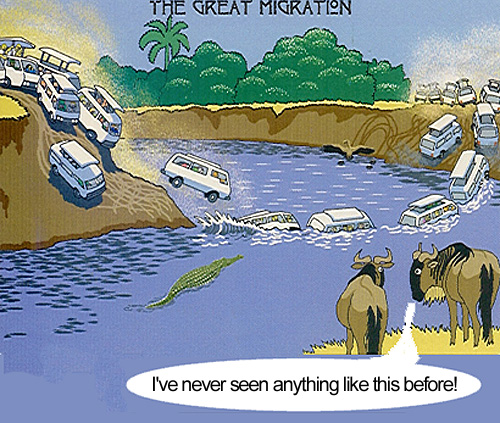

At least for now. Until we think we see a Dreamliner above the Mara cornfields, when it’s actually a monster locust coming in for the kill.