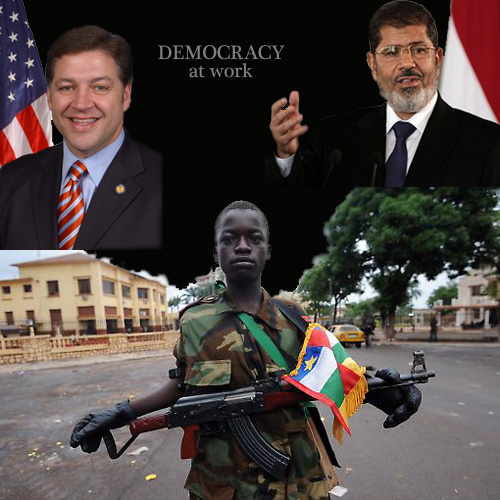

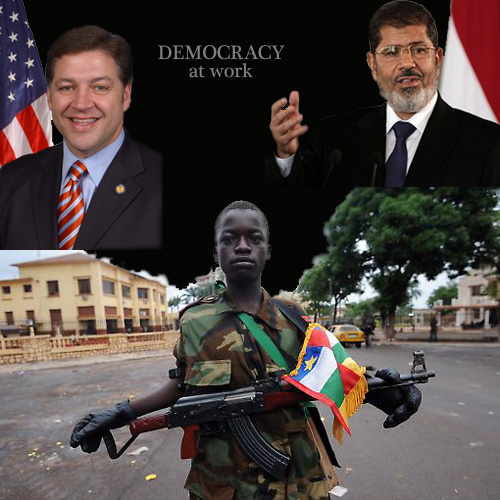

The trial of deposed Egyptian president Morsi, the bloodbath looming in the Central African Republic (CAR) and the new tribulations of Pennsylvania Congressman Shuster are all linked by the power and failure of democracy.

The trial of deposed Egyptian president Morsi, the bloodbath looming in the Central African Republic (CAR) and the new tribulations of Pennsylvania Congressman Shuster are all linked by the power and failure of democracy.

I’m not giving up on democracy, yet. But it needs some work. Here are the facts:

EGYPT

If ever there was a “Show Trial” in our lifetime it began today in Egypt, where the deposed president Mohamed Morsi is charged with murder. He and his co-defendants were defiant, shouting until their voices were hoarse. The trial, which carries the death penalty, next convenes on January 8.

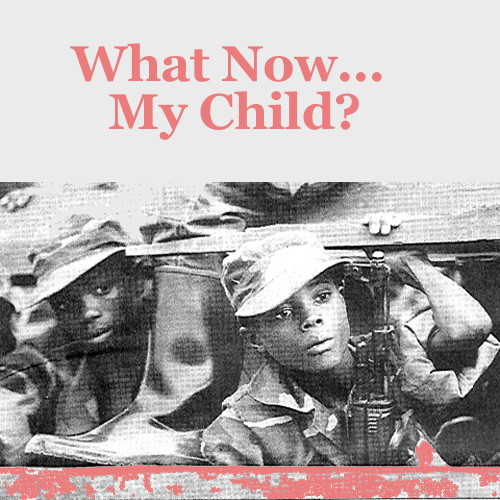

CAR

The country of 5 million in the middle of Africa will likely soon be the world’s next site of major genocide. NPR, the BBC and others interviewing UN staff in the country report today that genocide is imminent.

PENNSYLVANIA

Seven term Congressman and committee chair, Bill Shuster, a man about as conservative as you can get, faces a credible challenge from a Pennsylvania T-Party right-winger for having voted to end the government shutdown.

My take on the three ongoing events:

EGYPT: I’m glad Morsi was deposed by the military. He was destroying everything progressive in Egyptian society, defying the constitution including the judiciary, and essentially wrecking vengeance on a society for the long oppressed Muslim Brotherhood of which he was an important leader.

He had not yet quite started “rounding up the Christians” as former military leaders including Mubarak did to Muslims like himself, but he moved modern Egyptian society radically backwards, away from representative governance towards a dictatorship of Muslims that was polarizing society and aggravating the Christian/Muslim cleavage in society.

There was no mechanism in Egypt to get rid of a bad president, and that is the mantra used by progressives in Egypt today to justify the military coup. The irony, of course, is that had there been such a mechanism, Morsi would have prevailed over it since the fairly elected majority of the country and their elected representatives would never have voted to convict.

From far away, though, I feel the generals are going too far. They do not seem to believe that any compromise with the Muslim Brotherhood is possible, and that bodes very badly for the future of Egyptian stability.

CAR: What is happening, today, and going to happen in far worse measure very soon in the CAR is a failure of global institutions precisely because global institutions can’t navigate well the growing enmity between Christians and Muslims.

Note with great importance that in such a deep part of Africa, “Muslim/Christian” is actually a misnomer for any conflict. The ethnic divides, which are at the root of the conflict, existed long before Islam was born and perhaps before Christianity was born.

And as in Rwanda, all these various ethnic groups have lived together and intermarried and even shared languages for generations.

The Banda, Hausa, Fulfulde, Runga and similar ethnic groups in the north of the country, consider themselves “Muslim” especially in the current conflict. This is true even though practicing Muslims of the sort that pray regularly towards Mecca are rare. Many of these tribe were pretty undeveloped, remote jungle villages.

Almost all the rest of the ethnic groups are “Christian,” and they roughly occupy the south of the country and represent about two-thirds of the overall population including the only legitimate city and capital of Bangui. But they have no military support. The French long ago abandoned them.

The Muslims have no state support, either. But as the Obama/Holande alliance to crush al-Qaeda and its affiliates in Africa succeeds, the CAR is where the last guns, missile launchers, grenades and IUDs get dumped, and they are being dumped by fugitive Muslims on those in the CAR who call themselves native Muslims. So the one side is armed, and the other isn’t.

And the way it looks right now, nobody really cares. It seems the general consensus in the world is to just let everyone in the CAR destroy themselves. The UN Special Representative on Genocide said over the weekend, “We are seeing armed groups killing people under the guise of their religion…and decisively I will not exclude the possibility of a genocide occurring.”

PENNSYLVANIA:

Rep. Bill Shuster, like the father before him, represents a very rural part of southern Pennsylvania. Like so many other nonurban areas in America, it has not done well over my lifetime.

Median income has fallen, traditional life ways like independent farming have declined, even health statistics are worse than they were. In a nutshell, a father can no longer presume anything except that his children will be worse off than he was.

The reason for this is clear to me: a redistribution of wealth to the top of the pyramid. A cluster of power at the top oppresses those below with feudal outcomes like Walmart and phony mortgages followed by foreclosures.

But armed with money, the forces in power manipulate these folks to such a degree that they work constantly against their own self-interest. The most poignant example is how school referendum after school referendum is defeated.

Education is compromised to the point that no one in southern rural Pennsylvania has a clue as to why they’re more miserable than their folks. So…

… they blame the government. Add a pinch of “it couldn’t get worse than it already is” and a rather healthy American dose of revolution, and why not just close the government down?

All three of these examples are outcomes of failed democracy. Because all three situations are the result of democratic institutions paving their paths.

Egypt is clear. It was truly a fair and free election that brought Morsi to power.

In the CAR, which suffered ethnic conflict short of genocide for centuries, ethnic conflict is now oiled by the democratic processes of the west that permit if not encourage the sale of arms, by the “democratic choice” of Presidents Obama and Hollande to allow the CAR to be the “fire that burns out,” and the democratic (if highly filibustered) UN Security Council that has decided this spot on the world isn’t worth saving.

And in Pennsylvania it is people manifesting power in such a way that it returns to oppress them.

In each case, the value of self-determination turns against itself and democracy ends up destroying itself. Self-interest is compromised not for the betterment of the whole, but to destroy self-interest.

As I said, I’m not abandoning democracy. But someone with a really good stethoscope needs to take a look at it.

Today is Thanksgiving in the United States. (Canada celebrates it earlier.) Thanksgiving is one of Canada and the U.S.’ major holiday celebrations, characterized by copious amounts of food featuring seasonal recipes and lots of sweets. The traditional meat served at the feast is turkey.

Today is Thanksgiving in the United States. (Canada celebrates it earlier.) Thanksgiving is one of Canada and the U.S.’ major holiday celebrations, characterized by copious amounts of food featuring seasonal recipes and lots of sweets. The traditional meat served at the feast is turkey.