By Conor Godfrey

In 1884-85, European governments essentially drew a map of Africa on the back of a cocktail napkin in Berlin. This map carved Africa into a series of illogical states and spheres of influence that took little stock of realities on the ground and laid the framework for more than a century of civil strife.

Last week, the artificiality of the African political map was thrown into sharp relief by a series of tragedies.

Following the violence in central Nigeria, Muammar Gaddafi, well known for his misguided remarks and absurd costumes, suggested that Nigeria split into two states– one for the mainly Muslim North and one for the Christian and animist South.

On the other side of the continent, violence erupted in Sudan ahead of the planned referendum on an independent South Sudan.

Absurd borders are the rule not the exception in Africa. Europeans carved some of the great pre-colonial empires into unruly hodgepodges of people-groups who often lacked a shared history and had competing interests.

Look at the Gambia!

As the Europeans entrenched their rule, they imbued these imaginary lines with more and more meaning until state borders became faits accomplis. So what now?

The borders have created facts on the ground and there is no going back.

Mr. Gaddafi suggests Balkanizing the state(s) in question and equitably sharing resource wealth.

He uses the separation of India to substantiate his argument, but conveniently omits the ensuing civil strife and eventual civil war that took the lives of hundreds of thousands of people in that region.

He also appears to forget the previous attempt by the Igbo people to form their own state in South Eastern Nigeria. This event led eventually to the brutal Biafra-Nigerian war.

If Mr. Gaddafi wanted to partition every state in Africa that contains people groups deeply divided by tribe, ethnicity, or faith, he would quickly run out of fingers and toes.

This strategy would make more sense if religion and culture were truly at the core of these conflicts– but they are not.

Grazing rights, water rights, and land rights.

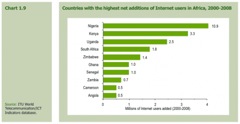

Access to political power, access to education, and access to jobs.

These are the flash points that drive conflicts in Africa.

Religion and culture will only fuel conflict when trampled on.

Even denying people a place to worship or undercutting some other important aspect of cultural identity rarely boils over into large-scale violent conflict unless people fear for the economic rights I listed above.

As conflicts persist, people tend to re-characterize resource based conflicts along ethnic or cultural lines, but I think that solving the resource and power-equity issues at the core of a dispute will eventually succeed in neutralizing the ethnic component.

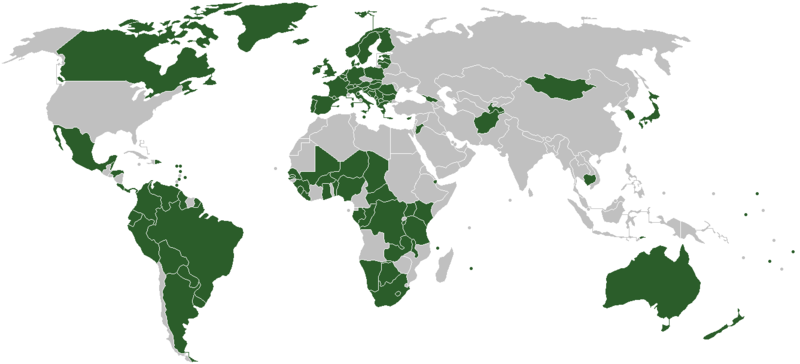

The most effective way to deal with the fallout of the Berlin conference would be to strengthen regional bodies. ECOWAS, SADC, COMESA, even the Arab League, and especially the African Union.

This will build regional and continent-wide capacity to enforce treaties, mediate between parties, commit peace-keepers to patrol sensitive territory, and knock heads together when necessary.

Currently the various regional groupings in Africa play an important but limited role. I think this might be changing…

While ECOWAS’ response to the recent slew of coups in West Africa drew criticism from some quarters for its inconsistency, its mediation eventually proved crucial to diffusing tensions.

SADC’s attempt to mediate in Zimbabwe (spearheaded by South Africa) has not had the desired result thus far, but even the lack of progress demonstrates the need for a regional body in Southern African with more clout.

Regional stakeholders in ECOWAS urgently need to enter the scene more forcefully in Nigeria. Perhaps Burkina Faso’s Blaise Compaore could build on his successful mediation in Guinea and the Ivory Coast by wading into Nigerian politics.

The upcoming elections in Sudan will also offer the African Union a chance to prove its worth.